4 Minutes

A daily pill might sound small. The effect could be meaningful. A wide review of randomized trials suggests omega-3 fatty acids — the kind commonly found in fish oil supplements — can reduce aggressive behavior by as much as 28 percent in the short term.

What the review found

Researchers pooled data from randomized, controlled trials spanning nearly three decades. In total they examined 29 trials with 3,918 participants, published between 1996 and 2024. Individual studies lasted on average about 16 weeks and covered a broad range of people, from children under 16 to adults in their 50s and 60s. The headline result was a modest but consistent reduction in aggression across different ages, sexes and clinical backgrounds.

Importantly, the effect was not limited to one kind of anger: the meta-analysis reported reductions in both reactive aggression — the heat-of-the-moment response to provocation — and proactive aggression, which is premeditated and goal-directed. That distinction matters because interventions that nip one form of aggression in the bud don't always touch the other.

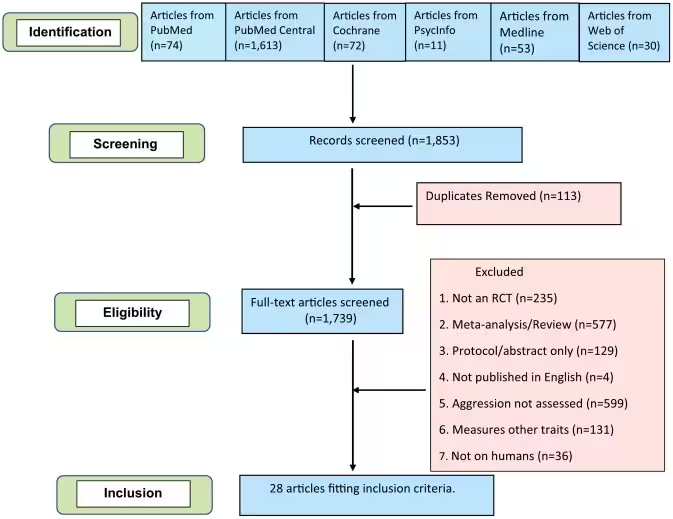

Flow diagram of literature search leading to 28 suitable papers.

Why omega-3 might matter biologically

Omega-3 fatty acids, including EPA and DHA, are integral to cell membranes and signalling in the brain. They also exert anti-inflammatory effects and influence neurotransmitter systems that regulate mood and impulse control. Put simply: what we eat can change how neurons fire and communicate.

Scientists have previously linked omega-3 intake to lower risks of certain psychiatric conditions and to cardiovascular benefits. The new meta-analysis builds on those threads by connecting dietary lipids to behavior in a measurable way. The authors propose that reduced neural inflammation and improved synaptic function could underlie the observed decline in aggressive acts, though the mechanisms remain to be pinned down by targeted biological studies.

Practical implications and caveats

Neurocriminologist Adrian Raine — one of the voices quoted when the review appeared — framed the findings pragmatically: if small nutritional changes can lower aggression across settings like schools, clinics and even the criminal justice system, implementing supplements or dietary adjustments is worth considering. He told readers that parents of aggressive children might try adding an extra portion or two of fish per week alongside other treatments.

Omega-3 is not a magic bullet, but evidence suggests it could be a low-risk tool in a broader strategy to reduce violent or antisocial behavior.

There are limitations to keep in mind. Most trials were relatively short; longer-term effects remain uncertain. Dosages varied between studies, and not every trial found a strong benefit. Publication bias and differences in how aggression was measured could also influence pooled estimates. Larger, longer randomized trials with standardized measures will be needed to confirm durability and to identify which populations benefit most.

Impacts beyond behavior

Adding omega-3s has potential collateral benefits: previous research links fish-oil–derived medications and supplements with lower risks of heart attack and stroke. That broader health profile strengthens the case for dietary discussion, though clinicians will weigh individual risks, medication interactions and dietary preferences.

For policymakers and clinicians, the question is not whether omega-3 will solve societal violence overnight, but whether a modest, inexpensive intervention could shift risk at the population level when added to existing programs.

If you are considering supplements, consult a healthcare provider about dose and form. Small changes in diet can ripple outward — and sometimes temper follows.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment