6 Minutes

Imagine a star hurled so fiercely that it escapes the Galaxy itself. Few things in astrophysics feel as cinematic as a massive star transformed into a cosmic cannonball.

From early clues to modern precision

In the 1960s, Adriaan Blaauw first noticed a population of stars moving at unusual speeds across the Milky Way. He proposed a neat, physical explanation: when one star in a close binary explodes as a supernova, the surviving star can be flung outward like shrapnel. Simple. Elegant.

But nature rarely reads our tidy models. Observers later found objects moving even faster — true hypervelocity stars — that required rethinking how these outliers gain their extraordinary speeds. Do exploding companions dominate? Or do chaotic gravitational encounters in crowded young clusters steal the show?

What the new survey looked at

Answering that question required two modern tools. First came Gaia: a long-running astrometric mission that has measured positions, motions, and basic physical properties for billions of stars. Second was IACOB, a spectroscopic campaign designed to fingerprint hot, massive OB stars across the Milky Way. Put them together and you get motion plus physical state for a large, uniform sample.

The Spanish-led team combined Gaia astrometry with high-quality spectra from the IACOB database to study 214 O-type stars — the rare, luminous, short-lived behemoths that dominate feedback in star-forming regions. The sample size and data quality make this the broadest observational study of runaway massive stars in our Galaxy so far.

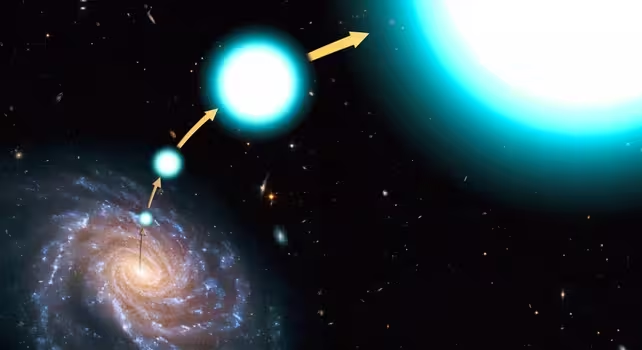

The hot, blue star HE 0437-5439 thrown from the center of the Milky Way with enough speed to escape the galaxy's gravitational clutches.

Rotation, binarity and the fingerprints of ejection

Rotation matters. A rapidly spinning massive star often carries a story of past interaction — mass transfer from a companion or the aftermath of a swapped dance in a tight binary. The survey finds a clear pattern: most runaway O stars are slow rotators. Those that spin quickly are far more likely to show signs of having been part of a binary disrupted by a supernova. In plain terms: rapid spin points toward an explosive origin.

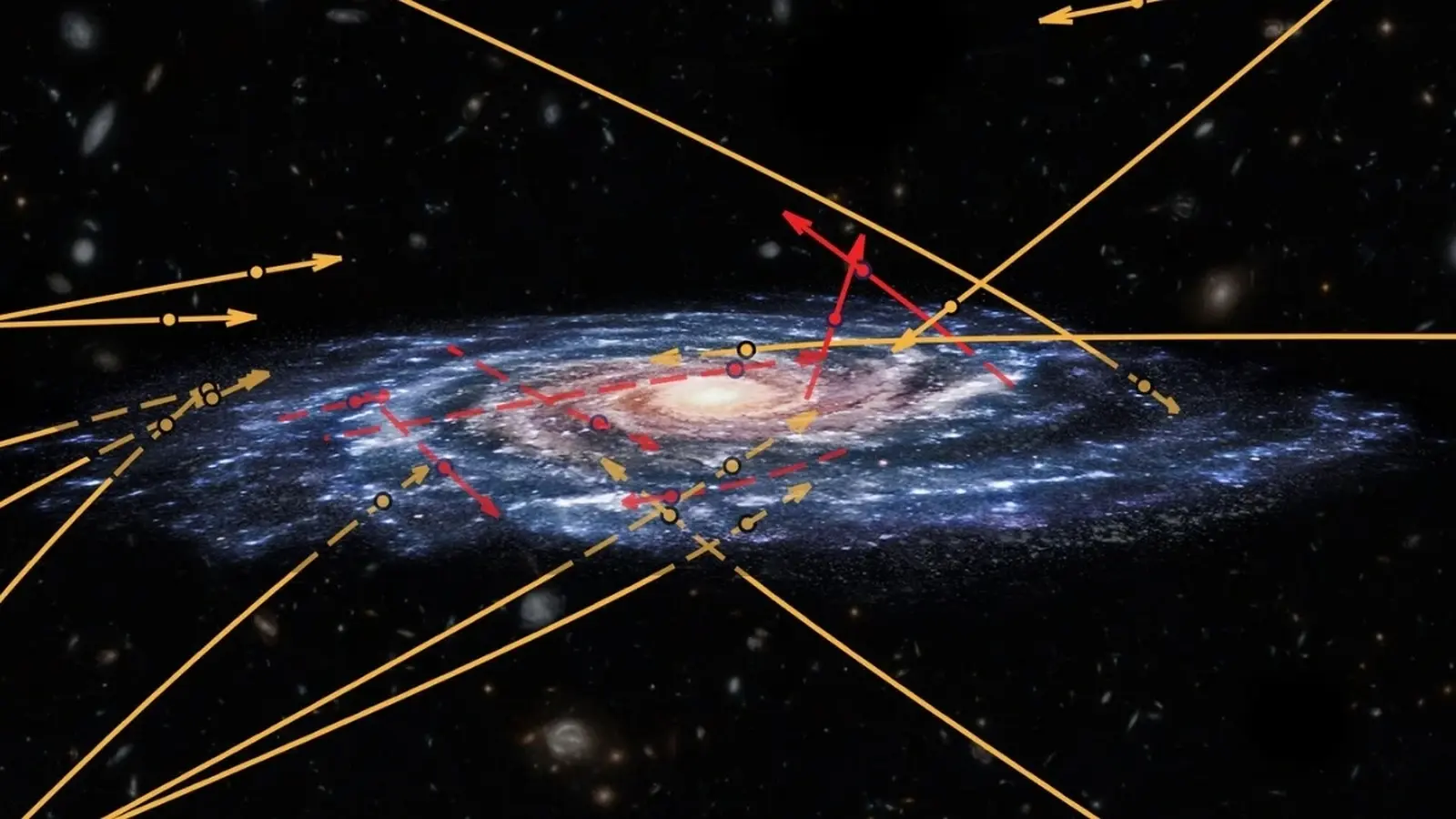

Velocities tell a parallel tale. The fastest stars in the sample — those exceeding several hundred kilometers per second and approaching the threshold that lets them escape the Milky Way’s pull — are commonly single. That suggests they were accelerated by strong gravitational encounters inside dense, young clusters: three-body slingshots, close passages with massive stars, or dynamical interactions that can eject a star without any need for an explosion.

Among the 214 O-type stars, the team identified 12 runaway binary systems. Three of these are X-ray binaries containing compact objects such as neutron stars or black holes; three more are prime candidates for hosting black holes. These findings show that both channels — supernova disruption and dynamical ejection — are active, but their relative importance varies with stellar spin and velocity.

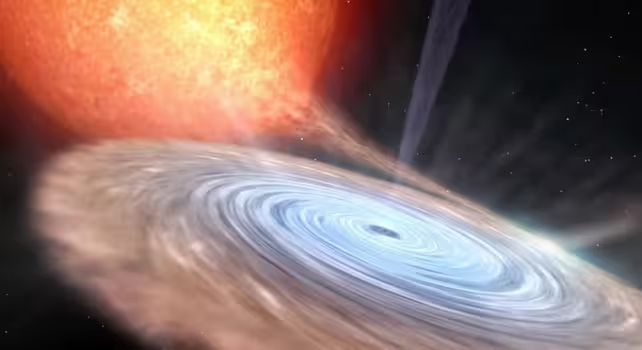

Artistic view of the accretion disc surrounding the black hole V404 Cygni, where the intense wind detected by GTC becomes evident.

Why this matters for galaxies

Runaway massive stars are not curiosities; they are agents of change. When a massive star escapes its birth cluster, its ultraviolet radiation and eventual supernova distribute energy and heavy elements far from where they formed. That redistribution affects the chemistry of the interstellar medium, the formation of subsequent stars and planets, and even the spread of elements central to life.

Understanding which pathways produce runaways refines our models of stellar evolution and helps predict where and how elements like oxygen and iron get mixed into the Galaxy. It also informs expectations for exotic systems: binaries that survive a supernova kick, compact-object pairs formed in unusual environments, and potential planetary systems that might endure under extreme conditions.

Expert Insight

"By combining rotation measurements with binarity diagnostics and precise Gaia motions, we can finally separate the fingerprints of explosions from those of dynamical violence in clusters," says Mar Carretero-Castrillo of ICCUB/IEEC, one of the study's lead authors, now at ESO. "These constraints let theorists test formation channels with data rather than guesswork."

Another perspective comes from a fictional senior astrophysicist synthesized from the community's voice: Dr. Elena Ruiz, specializing in massive-star feedback. "When a massive star leaves its nursery, it carries feedback to regions that otherwise would remain pristine. That changes how the next generation of stars forms — and where the heavy elements end up. The survey quantifies that conveyor belt."

Future Gaia data releases and continued spectroscopic follow-up will let astronomers trace runaways back to their birth sites with higher confidence. Pinpointing birth clusters will finally allow researchers to say, for any given runaway, whether the culprit was a supernova-blast or a gravitational slingshot — and to find rarer beasts: bound planetary systems surviving a stellar ejection, or binary systems that host black holes born without a visible supernova.

This study shows that no single explanation fits all runaway stars; the Galaxy uses multiple tools to fling its massive children into the void.

The next chapters will arrive when motion measurements grow even more precise and when surveys of compact remnants and X-ray sources extend deeper into the Milky Way — until then, every runaway star is a clue waiting to be traced back to its violent origin.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

astroset

Wow, cosmic cannonballs! The combo of Gaia + spectra is wild, makes me wanna trace every runaway back to birth.. if only data were perfect

Leave a Comment