6 Minutes

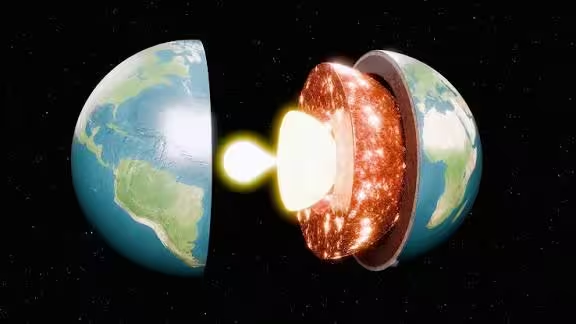

Imagine the most common element in the universe locked away where no bucket, pipe, or probe can reach. On the surface, Earth looks water-rich and hydrogen-obvious — oceans, rain, and organic molecules are everywhere. But what if most of the planet’s hydrogen never left the deep interior? New laboratory work suggests that the core may be a far larger storehouse of hydrogen than anyone realized, and that possibility reshapes how we think about where Earth’s water came from and how the planet has evolved.

Short version: hydrogen mixes readily with molten iron under extreme conditions. Long version: under conditions approaching those in Earth’s early core, hydrogen dissolves into iron-rich alloys and binds with silicon and oxygen, becoming effectively sequestered in the metallic heart of the planet. That process could hide enormous quantities of the element — not trace amounts, but as much as tens of times the hydrogen contained in all the world’s oceans.

Recreating core conditions in miniature

Researchers led by Dongyang Huang of Peking University used a diamond anvil cell to squeeze tiny samples to pressures of roughly 111 gigapascals while heating them to about 5,100 Kelvin. Those pressures and temperatures are close to the tolerances of Earth's deep interior — the outer core begins at roughly 136 gigapascals and the core’s temperature is thought to sit between about 5,000 and 6,000 K. Inside the anvil, a small iron sphere was embedded in hydrated silicate glass. Under extreme compression and heat the sample melted, components mixed, and iron, silicon, oxygen and hydrogen behaved as they might have during the molten, formative stages of the planet.

It’s an imperfect replica. Diamond anvil experiments can only run for seconds to minutes, and peak pressures fell a bit short of the core’s deepest values. Still, that fleeting window is enough to observe chemical reactions and partitioning behavior in ways that inform our models. In the experiment hydrogen moved into the iron alloy, and there it bonded with silicon and oxygen — a likely analog for how hydrogen could have been trapped in the forming core billions of years ago.

Geophysicists have long suspected the core contains light elements because seismic measurements show it’s less dense than pure iron. Silicon is already suspected to make up between 2 and 10 percent of the core by weight. Using those silicon estimates and the observed hydrogen-silicon bonding from the lab, Huang’s team estimated that hydrogen might account for about 0.07 to 0.36 percent of the core’s mass.

Numbers matter. That fraction translates to roughly 1.35 to 6.75 sextillion kilograms of hydrogen — between about 9 and 45 times the hydrogen locked in Earth’s oceans. Think of the planet appearing dry from afar, while hiding an enormous, metallic reservoir of the lightest element deep inside.

Why this matters: origins, cycles, and planetary comparisons

Sequestered hydrogen changes several narratives at once. First: the origin of Earth’s water. If so much hydrogen was captured in the core during accretion, then a significant portion of Earth’s water could have been delivered and trapped during the main stages of planet formation, rather than arriving later via icy comets. That rewrites timelines for volatile delivery and has implications for how and when surface oceans and atmospheres formed.

Second: core chemistry and dynamics. Hydrogen incorporated into iron alloys alters density, melting behavior, and electrical conductivity — factors tied directly to how Earth’s magnetic field is generated and sustained. A hydrogen-bearing core could change models of thermal and chemical convection in the outer core, altering our understanding of geomagnetic history.

Third: a broader planetary perspective. If hydrogen is easily drawn into metallic cores during formation, then rocky planets that look arid from remote observations might also hide internal reservoirs of volatiles. That affects how we interpret exoplanet observations and which worlds might host subsurface oceans or volatile-driven processes.

Huang’s paper is measured in its claims. The team notes that reaching definitive answers will require more experiments spanning the full range of core pressures and temperatures, improved models of element partitioning, and better constraints on early Earth accretion chemistry. Still, the result is striking: the hydrogen we find in oceans and rocks might be a small sample of Earth’s true inventory.

Expert Insight

“If these results hold up, they force a re-evaluation of volatile budgets during planetary formation,” says Dr. Leah Rivera, a planetary geochemist at the University of Arizona. “Hydrogen in the core alters not only where water comes from, but how planets lose or retain volatiles over time. That’s fundamental to understanding habitability.”

More laboratory work will follow. Researchers will push pressures and temperatures higher, explore different alloy compositions, and refine how hydrogen, silicon and oxygen interact under core-like conditions. In parallel, seismology, geomagnetism, and high-pressure mineral physics will test the consequences of a hydrogen-bearing core. The planet keeps its secrets deep. But with each experiment, the veil lifts a little further, and Earth’s inner chemistry begins to make more sense.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

labcore

wow didnt expect that, if Earth's hiding oceans in its core that's wild. Makes you rethink comets and early Earth, if that's real then whoa

Leave a Comment