6 Minutes

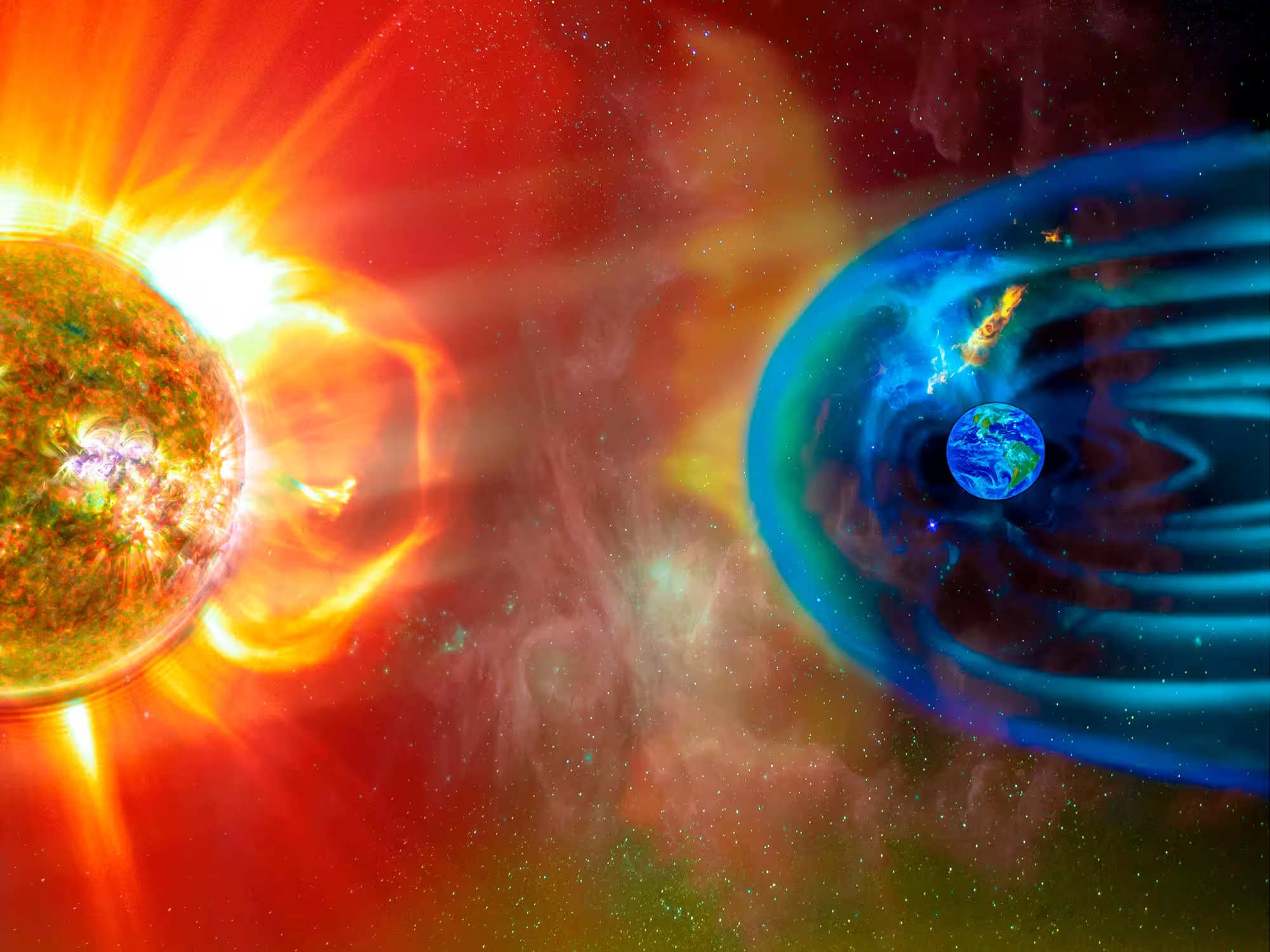

Imagine a solar flare happening hundreds of millions of kilometers away, ripples of charged particles sweeping past Earth, and a fault zone deep underground already teetering on the edge. Could those distant charged winds add the tiniest, final shove that triggers a rupture? It sounds like science fiction. Recent theoretical work from researchers at Kyoto University asks precisely that — and frames the question in physical, measurable terms.

Researchers propose a model suggesting that disturbances in the ionosphere, driven by solar activity, may under certain conditions exert forces on fragile regions of Earth’s crust.

How the ionosphere and crust could talk to one another

The ionosphere is a patchwork of charged particles sitting tens to hundreds of kilometers above our heads. Satellites, GPS signals, and radio waves routinely reveal its state because those signals change as they pass through. Scientists already monitor total electron content (TEC) to track space weather; it turns out those same measurements can reveal abrupt reorganizations after strong solar flares or coronal mass ejections.

The Kyoto model links those upper-atmosphere charge shifts to processes in faulted rock. Picture a fractured rock zone deep in the crust that traps hot, pressurized fluids — perhaps even reaching a supercritical state. In the model, that damaged zone behaves electrically like a capacitor: it stores charge across tiny voids and connects, via capacitive coupling, to the surface and the lower ionosphere. In other words, the crust and the ionosphere become components of one extended electrostatic system rather than isolated layers.

When a solar event suddenly boosts electron density at lower ionospheric altitudes, the model proposes that this change doesn’t remain confined overhead. Because the two regions are electrically coupled, a surge in atmospheric charge can translate into intensified electric fields inside nanometer-scale voids within fractured rock. These are extreme scales, yes, but the physics matters: electric fields concentrated in small cavities change the pressure there, and pressure influences how cracks grow and coalesce.

Why would any of that matter for a real earthquake? Because many faults sit close to failure. Small nudges — tidal stresses, slow aseismic slip, fluid pressure changes — are known to affect timing. The Kyoto calculations show electrostatic pressures inside these microscopic cavities can reach several megapascals under large ionospheric disturbances, comparable to other subtle forces that modulate fault stability.

Evidence, limits, and a two-way street

There is empirical context for these ideas. Before some large earthquakes, researchers have recorded anomalous ionospheric signatures: elevated electron density, an apparent lowering of ionospheric altitude, and atypical propagation of medium-scale traveling ionospheric disturbances. Historically, such signals were interpreted mainly as responses to stress or gas release from the crust — a bottom-up coupling. The Kyoto model introduces the complementary possibility: top-down feedback, where ionospheric dynamics also exert mechanical influence on crustal failure processes.

Important caveats follow. The authors emphasize this is not an earthquake forecasting tool. The proposed mechanism requires a confluence of conditions: an intense solar disturbance that alters TEC by several tens of units, a crustal zone with trapped fluids in a susceptible phase, and a fault already close to rupture. Temporal coincidence of solar activity and seismic events — for example around the 2024 Noto Peninsula earthquake in Japan — is intriguing but not proof of causation.

What the model does offer is a quantitative pathway: satellite-observed ionospheric shifts translate into predictable changes in electric field and pressure inside rock voids. That pathway can be tested. The authors call for coordinated observations combining high-resolution GNSS-based ionospheric tomography, in situ subsurface monitoring, and controlled laboratory experiments on electrically active fractured rock under pressure and temperature conditions that mimic the deep crust.

Expert Insight

'The novelty here is the electrostatic coupling,' said Dr. Kenji Sato, a fictional geophysicist speaking as an informed observer. 'We often think of earthquakes as purely mechanical failures. This model reminds us that electrical and plasma physics can intersect with rock mechanics in subtle but testable ways.' He suggested experiments that combine rock deformation rigs with applied electric fields and simultaneous measurements of microcrack evolution to validate the calculations.

Technologies already exist to move this research from theory toward data-driven evaluation. GNSS networks can resolve TEC changes with increasing spatial and temporal precision. Satellite missions that measure ionospheric plasma, ground-based magnetometers, and borehole observatories that record fluid pressure and electric potentials in faults could be coordinated around periods of intense solar activity. If the model’s fingerprints appear consistently — small, transient electrostatic signatures coincident with enhanced TEC and microphysical precursors — the hypothesis gains traction.

At stake is a broader view of Earth as an interconnected system: not just lithosphere, not just atmosphere, but an electrodynamic continuum that occasionally passes signals both ways. Whether those signals ever amount to a decisive push remains to be tested, but the idea widens the kinds of data scientists should collect when probing earthquake initiation. It also opens a modest door: can we someday integrate space weather monitoring into multi-parameter seismic hazard research? The answer will depend on data, careful experiments, and a willingness to listen to the sky.

Source: scitechdaily

Leave a Comment