6 Minutes

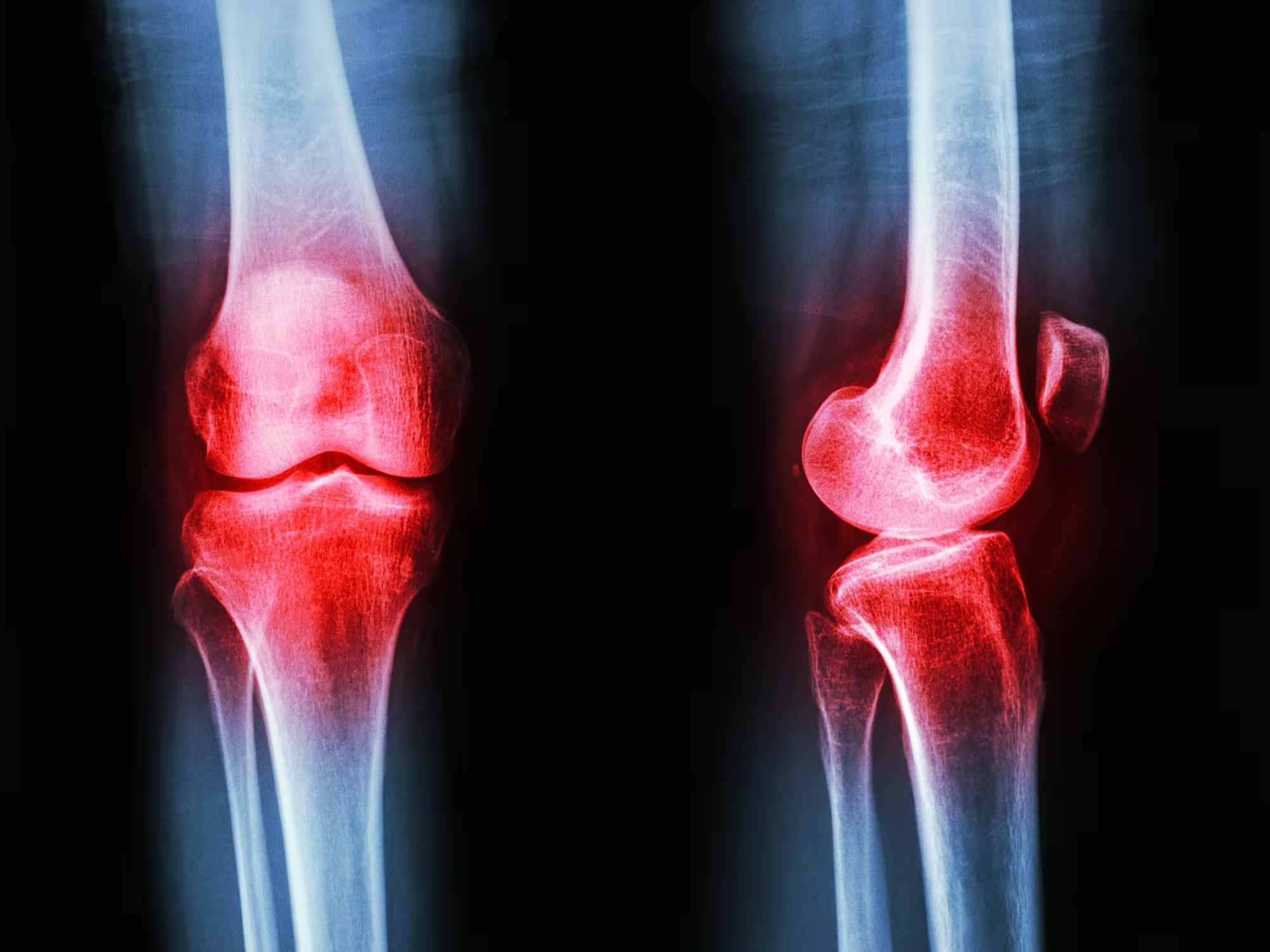

Stiff knees, sore hips and constant joint ache are often accepted as a normal part of getting older. But mounting evidence shows osteoarthritis is not simply "wear and tear"—and the single most effective treatment for many people is not a pill or a scalpel, it’s movement. Here’s what patients and clinicians need to know about exercise as frontline therapy for joint disease.

Why movement matters: how joints stay healthy

Cartilage—the smooth tissue that cushions bones inside a joint—has no direct blood supply. That means it depends on motion to receive nutrients and remove waste. When you walk, squat or cycle, cartilage is compressed and released like a sponge: fluid flows out and then back in, carrying fresh nutrients and natural lubricants that keep the tissue resilient.

This mechanical exchange explains why the old idea of osteoarthritis as passive "wear and tear" is incomplete. Rather than steadily degrading with use, joints are dynamic systems that respond to stress by repairing and adapting. Regular, appropriately dosed activity stimulates those repair processes and helps maintain joint structure and function.

Osteoarthritis is a whole-joint problem

We now understand osteoarthritis as a disease of the entire joint: cartilage, synovial fluid, subchondral bone, ligaments, surrounding muscles and the nerves that coordinate movement can all be involved. Exercise targets many of these elements at once.

Muscle weakness is an early and modifiable risk factor. Strong muscles act as shock absorbers and stabilizers, reducing excessive joint loading. Neuromuscular control—how muscles and nerves coordinate—can be improved through balance, proprioception and movement-quality training. Programs such as GLA:D® (Good Life with osteoArthritis: Denmark) combine these approaches in supervised group sessions and have reported meaningful reductions in pain and improvements in function that persist for months after completion.

What the evidence says: exercise reduces pain and protects joints

Large reviews and clinical trials consistently place exercise among the strongest non-surgical treatments for hip and knee osteoarthritis. Benefits include:

- Reduced pain and stiffness

- Improved joint function and mobility

- Greater muscle strength and balance

- Positive effects on inflammation and metabolic health

Regular activity lowers systemic markers of inflammation and can change the cellular environment within joint tissues. For people with excess weight, exercise helps not only by reducing mechanical load but also by improving metabolic profile—lowering inflammatory molecules that can accelerate cartilage breakdown.

Gaps between evidence and practice

Despite strong evidence, health systems around the world still underuse exercise as a treatment. Studies from Ireland, the UK, Norway and the United States show fewer than half of patients with osteoarthritis are referred to exercise programs or physiotherapy by their primary clinicians. Many receive treatments clinical guidelines advise against, and a substantial proportion are fast-tracked to surgical consultation before non-surgical options have been fully explored.

Barriers include limited access to supervised programs, short appointment times that prioritize imaging or medications, and the misconception—among patients and some clinicians—that activity will worsen joint damage. The science points the other way: targeted, progressive exercise is protective.

Practical exercise strategies that work

Not all activity is identical. Effective osteoarthritis programs combine several elements tailored to the individual:

Resistance training

Progressive strength exercises (bodyweight, bands or weights) build muscles that support the joint and reduce harmful loads.

Aerobic conditioning

Low-impact cardio—walking, cycling, swimming—improves endurance, metabolic health and pain tolerance. It also supports weight management, a key factor in knee and hip osteoarthritis.

Neuromuscular and balance work

Exercises that improve coordination, balance and movement quality (such as those in GLA:D®) reduce instability and help patients regain confidence in everyday tasks.

Load management and progression

Start at tolerable levels, increase intensity gradually, and focus on consistent sessions (for many people, two to three strength sessions plus aerobic activity per week). Physiotherapists can tailor programs to pain response and comorbidities.

Exercise before surgery: why it matters

There are currently no disease-modifying drugs for osteoarthritis. Joint replacement can be transformative for some, but it carries risks and does not guarantee perfect outcomes. Because exercise reduces pain, improves function and can delay (or in some cases reduce the need for) surgery, clinical guidelines recommend trying structured, supervised exercise before moving to invasive options.

Even when surgery is eventually required, people who have followed preoperative exercise programs often recover faster and experience better postoperative outcomes. Exercise is a low-risk, high-value intervention that should be maintained throughout all stages of the disease.

Expert Insight

"We used to tell patients to 'rest the joint'—now we know that's often the wrong message," says Dr. Emma Collins, a physiotherapist and researcher specializing in musculoskeletal health. "Targeted exercise rebuilds strength, retrains movement patterns and can reduce inflammation at a molecular level. The goal is not simply to move more, but to move smarter: progressive, supervised programs that match a person's capacity and goals."

How patients and clinicians can act today

Patients should ask clinicians about structured exercise or physiotherapy early in their care pathway. Useful questions include:

- Which types of exercise are safest and most effective for my joint?

- Can I be referred to a supervised program like GLA:D® or to a physiotherapist experienced in osteoarthritis?

- How should I progress exercises and what pain levels are acceptable during training?

Clinicians should prioritize evidence-based, non-surgical interventions and ensure referrals to exercise specialists are available and affordable. Health systems can scale effective group-based programs and telehealth models to close the gap between evidence and practice.

This article is adapted from reporting originally published in The Conversation. Funding disclosure: the original reporting noted research support for osteoarthritis studies. Exercise is not a cure-all but, for many people, it is the most effective, low-risk intervention available—one that also benefits cardiovascular health, mood and long-term wellbeing.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

Marius

Is it really safe to push through pain a bit? I mean, progressive strength makes sense, but who decides 'acceptable pain' during training? idk

atomwave

wow, didn't expect exercise to be such a game changer for creaky knees. kinda relieved but also annoyed I waited so long lol. gonna try the strength stuff.

Leave a Comment