9 Minutes

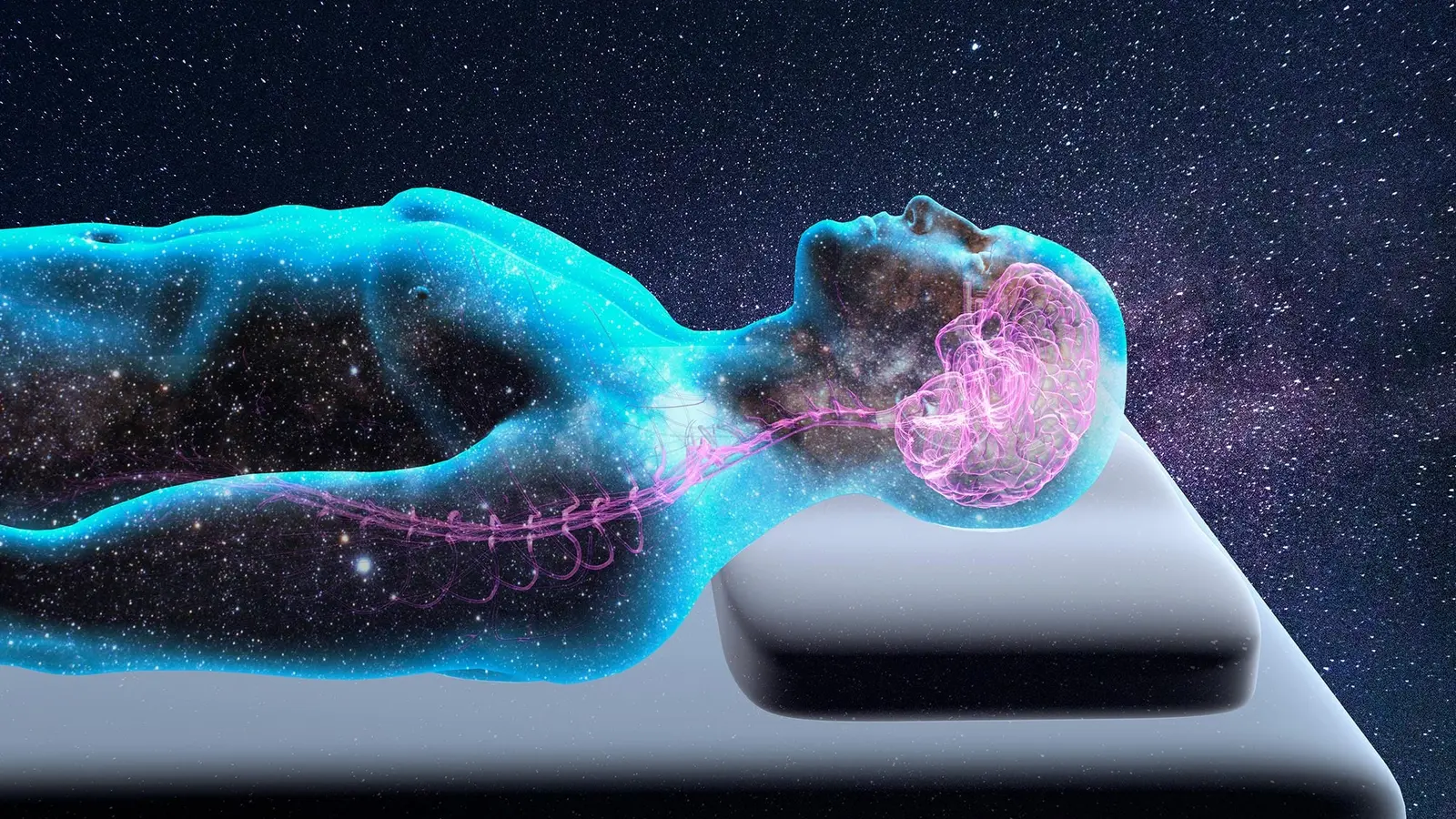

A new noninvasive brain stimulation method — transcranial focused ultrasound — is poised to change how scientists investigate one of science’s oldest puzzles: how physical activity in the brain creates conscious experience. Researchers at MIT and collaborating institutions have published a practical roadmap for using this technology to move from correlation to causation in consciousness studies, opening opportunities to test competing theories and probe deep brain regions once accessible only during surgery.

Why focused ultrasound matters: a new lever on the living brain

Consciousness research has traditionally relied on observational tools: MRI to map brain structure, EEG to measure electrical rhythms, and behavioral experiments to infer perception and awareness. Those methods are powerful for describing which brain areas light up during a task, but they leave a central scientific question unanswered: which neural processes actively generate conscious experience, and which simply follow it?

Transcranial focused ultrasound (tFUS) offers a different approach. By sending precisely focused acoustic energy through the skull, tFUS can modulate neurons in a region only a few millimeters across, reaching subcortical structures centimeters beneath the scalp. Unlike invasive electrical stimulation, this method requires no surgery and can reach deeper brain targets with a spatial precision that rivals — and in some cases exceeds — other noninvasive techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) or transcranial electrical stimulation (tES).

That ability to perturb activity directly gives researchers a causal tool: change activity in a defined area, and observe whether perception, pain, or thought also change. If a targeted manipulation alters conscious experience, that region is likely a generator or essential component of that experience, not merely a bystander.

From theoretical debate to testable experiments

One immediate scientific payoff for tFUS is the ability to test competing frameworks for consciousness. Broadly speaking, two camps dominate current debate. The "cognitivist" view argues that conscious experience requires higher-order processes — integration across distributed brain networks, especially involving frontal areas that handle reasoning, attention, and self-reflection. By contrast, the "non-cognitivist" perspective suggests that specific, perhaps localized neural patterns suffice for particular experiences: vision, pain, or simple sensations could arise from activity in posterior cortex or deeper subcortical circuits without invoking broad frontal machinery.

tFUS experiments can be designed to adjudicate these ideas. For example, researchers can use focused pulses to transiently disrupt activity in the prefrontal cortex while volunteers view visual stimuli. If conscious perception vanishes or changes, that supports the idea that frontal networks are necessary. If perception persists despite frontal disruption but is sensitive to stimulation of posterior or subcortical sites, that would favor a more localized origin for certain experiences.

Researchers can also explore the binding problem: how distinct sensory inputs from different brain regions combine into a unified conscious scene. By selectively turning up or down activity in separated nodes of the visual system and measuring subjective reports ("Did you see a flash? Was it vivid or dim?"), scientists can test how distributed networks synchronize to produce a single unified perception.

Planned experiments and practical considerations

Teams at MIT and partner institutions are moving from theory into practice. Early experiments will focus on the visual cortex, where stimulus conditions and subjective reports can be tightly controlled. Visual tasks provide an accessible window into perception: researchers can present light flashes, vary contrast or timing, and correlate those changes with subjective reports and simultaneous EEG recordings.

Subsequent studies will expand to higher-level areas in the frontal cortex and to subcortical targets implicated in emotion and pain. Pain is a particularly intriguing test case: we often withdraw from a hot surface before the conscious sensation of pain fully registers. Which circuits produce the conscious feeling? Cortical regions, deeper brain nuclei, or a combination? tFUS can alter activity in candidate regions and reveal whether those changes shift people's reports of pain intensity or quality.

Designing such experiments requires careful safety and measurement protocols. tFUS parameters — intensity, pulse pattern, focus location — must be calibrated to modulate activity without causing tissue damage or heating. Combined recordings, such as EEG or functional MRI, will help investigators read out network-level effects and ensure that observed behavioral changes reflect neural modulation rather than nonspecific factors like auditory or somatosensory arousal.

"This tool lets you stimulate different parts of the brain in healthy subjects in ways you couldn't before," says an investigator on recent roadmap discussions. “It's not only useful for medicine or basic science, but it could help address the hard problem of consciousness by pinpointing circuits that generate sensation and thought.”

Scientific background: how acoustic energy affects neurons

Focused ultrasound interacts with brain tissue through mechanical and possibly thermal mechanisms. Low-intensity pulses produce mechanical displacement and micro-scale pressure changes that can alter neuronal membrane properties and synaptic function. At properly controlled intensities, these effects modulate firing rates and network dynamics without causing permanent change.

Because acoustic beams can be steered and focused, researchers can target regions that lie beneath the cortex — for example, thalamic nuclei, basal ganglia, or midline structures that have been difficult to reach noninvasively. Targeting precision depends on skull anatomy and ultrasound frequency; modern systems use imaging guidance and computational models of skull transmission to optimize focus.

Comparisons with other brain stimulation tools

- TMS and tES: Usually limited to cortical surface regions and produce broader, less focal fields.

- Deep brain stimulation (DBS): Highly specific but invasive — requires surgical electrode implantation.

- tFUS: A bridge between noninvasive convenience and deep, focal access — potentially enabling controlled experiments in healthy volunteers.

Implications: what could we learn — and why it matters

At the core of consciousness science is the distinction between circuits that merely correlate with awareness and circuits that are necessary to create it. Establishing necessity matters for both basic science and medicine. If specific subcortical networks play a larger role in pain or emotional qualia than currently recognized, that could reshape therapeutic strategies for chronic pain, PTSD, or depression. Noninvasive modulation of those sites might one day complement or replace invasive interventions.

From a theoretical perspective, causal experiments could sharpen or falsify rival theories. If disrupting frontal hubs consistently abolishes certain conscious contents, integrated-information or global workspace theories that rely on widespread cortical integration will gain empirical support. If, instead, localized posterior or deep structures prove essential, theorists will need to revise assumptions about where consciousness arises.

Beyond theory, tFUS may also accelerate discovery in cognitive neuroscience more broadly. Access to deep nodes with high spatial specificity would let researchers probe memory circuits, emotional regulation centers, and reward pathways in controlled, reversible ways. That could speed translation from laboratory discovery to clinical interventions.

Expert Insight

"The promise of transcranial focused ultrasound is that it gives us a reversible lever to test hypotheses that have been speculative for decades," says Dr. Elena Vargas, a fictional but realistic cognitive neurologist and neurotechnology researcher. "Imagine being able to transiently reduce activity in a thalamic nucleus and watch how a subject's visual awareness changes in real time. That kind of causal data is essential if we want to move beyond mapping to mechanistic explanations."

Dr. Vargas warns that results will not be binary. "Consciousness is messy — it's likely built from redundancies and overlapping systems. tFUS will reveal gradients and interactions rather than on/off switches. Still, every controlled perturbation narrows the field of viable theories."

Related technologies and future prospects

tFUS will not replace existing imaging and stimulation approaches; rather, it complements them. Combined protocols that pair focused ultrasound with EEG, MEG, or fMRI can link localized perturbations to network responses, offering a multi-scale view of brain computation. Advances in modeling skull transmission and using closed-loop stimulation — where neural readouts guide stimulation in real time — could make interventions more precise and adaptive.

Regulatory and ethical frameworks will also need to keep pace. Noninvasive access to deep brain regions raises important questions about consent, the limits of modulation, and the potential for cognitive enhancement. Responsible research practices, transparency, and careful safety monitoring will be essential as human studies expand.

Researchers publishing the roadmap emphasize that this is an early-stage tool with high potential and manageable risk: low-intensity protocols, careful subject screening, and incremental experiments can chart a path to robust findings without premature clinical claims.

Ultimately, the arrival of transcranial focused ultrasound in consciousness research marks a shift from observation to intervention. By turning parts of the brain up or down and watching which conscious experiences change, scientists can begin to separate the causes of consciousness from its consequences — a necessary step if we are ever to understand how subjective experience arises from biology.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

neuroKit

interesting roadmap but feels a bit optimistic , real brains messy, results likely graded not binary. still, cool tool if done carefully

Armin

is this even ready for humans? skull variability, auditory confounds, placebo effects... curious but skeptical, needs more replication

cogflux

wow ok this is wild. noninvasive but reaches deep? if true this could flip how we study mind, but safety first pls ...

Leave a Comment