7 Minutes

Astronomers have discovered an unexpected and puzzling structure at the core of the Ring Nebula: a long, straight bar composed of glowing, ionized iron. The feature—unlike anything seen in a planetary nebula before—raises fresh questions about how dying Sun-like stars shed material and how dust and metals behave in these late stellar stages.

How a familiar nebula suddenly got strange

The Ring Nebula (Messier 57), a well-known planetary nebula about 2,570 light-years away in Lyra, has been studied for nearly 250 years. Planetary nebulae are the elegant, colorful shells that form when stars similar to the Sun expel their outer layers as they transition to white dwarfs. Because that process is relatively gentle, these objects often appear symmetric and well understood—so finding a straight, glowing bar of ionized iron cutting across the Ring’s center was a genuine surprise.

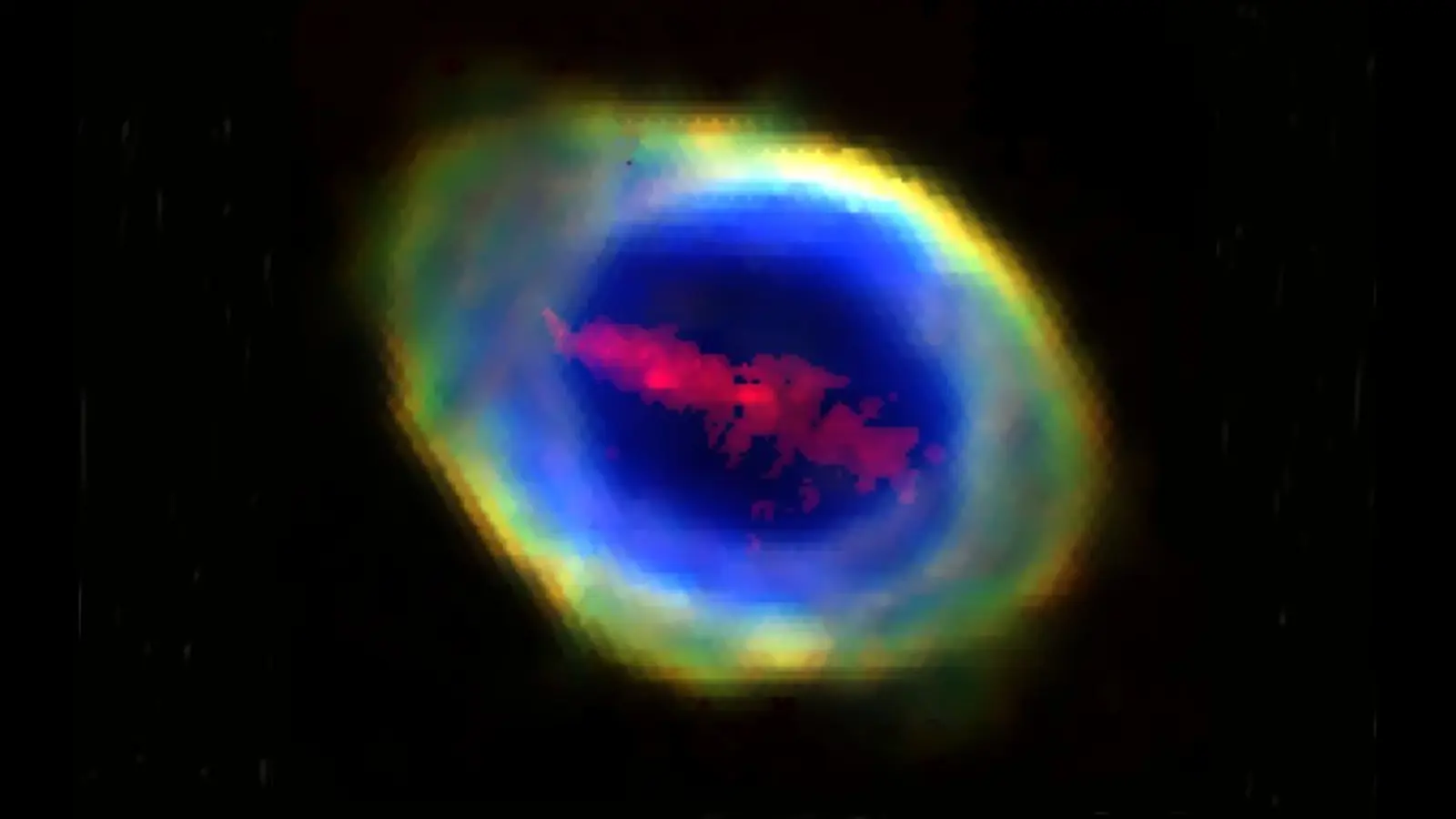

JWST image of the Ring Nebula.

This iron bar was revealed in new spectroscopic maps captured with the WEAVE instrument on the 4.2-metre William Herschel Telescope (WHT). Using WEAVE’s Large Integral Field Unit (LIFU) mode, the team obtained a contiguous spectroscopic view of the entire nebula—rather than the narrow, slit-shaped slices used by earlier studies. That approach exposed structures that slit spectroscopy could easily miss unless a slit happened to cross the feature by chance.

What makes this iron bar so baffling?

Several properties of the bar challenge conventional explanations. First, the structure appears largely composed of bare, ionized iron atoms—an enormous amount, roughly equivalent to a significant fraction of Earth’s mass, according to the initial analysis. In planetary nebulae, metals such as iron are usually locked in dust grains rather than existing as free, glowing atoms. Second, the bar’s kinematics don’t match expected signatures for familiar phenomena.

- The white dwarf at the center of the Ring Nebula is offset from the bar’s centerline, so the bar can’t be a straightforward jet launched from the remnant star.

- Velocity measurements along the bar show the whole feature is receding from us, rather than showing opposite Doppler shifts at either end that you would expect from bipolar jets.

- No other emission lines in the nebula trace the same linear shape—this iron emission is unique in morphology.

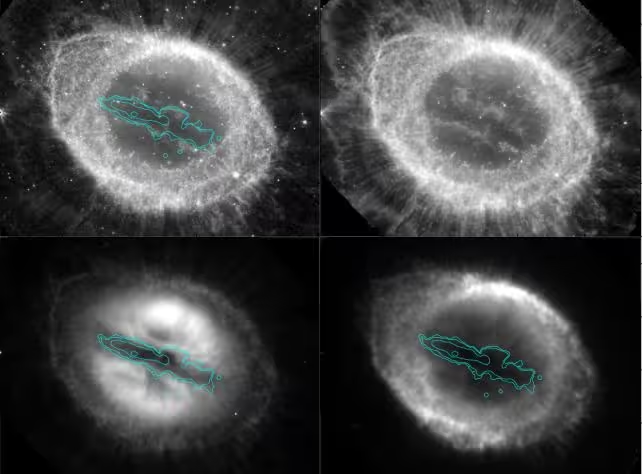

JWST observations of the nebula, with the iron outlined in blue, except in the top right, where it is omitted to show the dust.

One hypothesis is that a large reservoir of dust was destroyed along a narrow region, releasing iron atoms into the gas phase. Images from the James Webb Space Telescope show dust on both sides of the bar but not overlapping it, lending some support to that idea. However, destroying dust and freeing iron would require intense shocks or very high temperatures—signatures that are not observed in the nebula’s calm center.

Could the bar be torn planetary debris?

The press materials accompanying the discovery mention the provocative suggestion that disrupted planetary material might be responsible. While a shredded planet could supply iron-rich debris, this scenario struggles to explain several facts: debris from a disrupted planet would be expected to show mixed elements (magnesium, silicon, etc.), produce a clear orbital or expansion velocity pattern, and generally form a more diffuse or clumpy distribution—not a straight, coherent bar. None of those expected signatures match the new observations.

Perspective and geometry matter

We also must remember projection effects. The bar could be a larger flattened structure viewed nearly edge-on, making it appear thin and linear. If the bar extends toward and away from us out of the plane of the sky, its true three-dimensional shape and motion could be quite different from what we infer from a single viewing angle.

Instruments and methods: why WEAVE made the difference

The discovery highlights how modern integral-field spectroscopy can change our picture of familiar objects. WEAVE’s LIFU mode collects spectra across a wide field in one exposure, giving both spatial and spectral information for every point in the nebula. That allowed the research team, led by Roger Wesson (Cardiff University), to map the distribution of iron emission across the entire Ring and identify the bar where slit spectroscopy never did.

Roger Wesson and colleagues noted that many nebulae have been observed repeatedly with different telescopes, but WEAVE’s combination of field size and spectral coverage provided a qualitatively new dataset. According to Wesson, seeing the bar emerge from the processed data was striking and unexpected, and it underlines how instrument advances continue to reveal previously hidden phenomena even in well-studied objects.

Why this matters for planetary nebula science

If the iron bar proves not to be unique, finding similar structures in other planetary nebulae would reshape our understanding of dust processing, metal transport, and the late-stage environments around Sun-like stars. The presence of large amounts of free iron carries implications for how dust grains survive or are destroyed, how planets or planetesimals interact with evolving stars, and how metals cycle back into the interstellar medium.

Beyond the immediate puzzle, the discovery is a reminder that the life cycles of stars and their planetary systems are interconnected in complex ways. Planetary debris, dust physics, binary companions, magnetic fields, and transient shocks could all play roles—some newly revealed by deeper, wider spectroscopic surveys.

Expert Insight

"This iron bar is a textbook example of why we need both broad surveys and targeted follow-ups," says Dr. Elena Morales, an astrophysicist who studies late-stage stellar evolution. "Integral-field spectrographs give us the three-dimensional spectral maps necessary to spot oddities that slit spectroscopy misses. If similar iron structures appear in other nebulae, we’ll need to revise our models of dust destruction and metal redistribution in stellar ejecta."

The research has been published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, and the team plans to search archival and new integral-field data for additional examples. Each fresh detection will be a clue: is the Ring’s bar a rare fluke, the remnant of a destroyed planet, or the visible trace of a more general physical process that has until now escaped notice?

As astronomers expand spectroscopic surveys of planetary nebulae with WEAVE, JWST, and other facilities, the hope is to build a sample large enough to test competing explanations. Until then, the Ring Nebula’s iron bar remains a striking and unresolved fingerprint of stellar death—and an invitation to look again at objects we thought we already knew.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

skyspin

hmm could this be just a projection effect? seems odd that only iron shows up, where r the other metals... or are we missing something in the models?

astroset

Wait, a straight bar of glowing iron? mind blown. How did the dust just vanish like that, weird shocks or planet bits? gotta see followups!

Leave a Comment