4 Minutes

Researchers have uncovered a common genetic thread linking eight major psychiatric conditions, revealing how certain gene variants act across brain development and may influence multiple disorders. The new findings point to shared molecular pathways that could become targets for therapies addressing more than one illness at a time.

Shared genetic signals across eight conditions

In an expanding picture of psychiatric genetics, a US-based team built on earlier international work to map how the same genes contribute to diverse diagnoses. Back in 2019, researchers identified 109 genes that appeared in different combinations across autism, ADHD, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, Tourette syndrome, obsessive-compulsive disorder and anorexia. That overlap offered a biological explanation for why these conditions often co-occur in individuals and families.

Human precursor neurons with protein expression stained in different colors, indicating the type of neurons developing.

The recent study, published in Cell in early 2025, dug deeper. Instead of only listing implicated genes, investigators tested nearly 18,000 genetic variants drawn from both the shared gene set and the disorder-specific genes. They introduced these variants into human neuronal precursor cells to observe effects on gene regulation during critical windows of brain development.

Methods that reveal when and how genes act

By modeling variant activity in developing human neurons and then validating findings in developing mouse neurons, the team identified 683 variants that measurably change regulatory activity. Many of these changes are pleiotropic: a single variant influences multiple traits or conditions. Those pleiotropic variants were not only active across a wider range of brain cell types, they also engaged in far more protein-to-protein interactions than variants unique to a single disorder.

What pleiotropy means here

Pleiotropy—where one genetic change affects several biological processes—helps explain overlapping symptoms and diagnostic co-occurrence. "The proteins produced by these genes are also highly connected to other proteins," explained University of North Carolina geneticist Hyejung Won. "Changes to these proteins in particular could ripple through the network, potentially causing widespread effects on the brain."

This network perspective matters because many pleiotropic variants remain active across extended developmental windows, potentially influencing cascades of gene regulation from early neuronal differentiation through later maturation. In practical terms, a single variant can nudge multiple developmental stages and cell types, producing diverse clinical outcomes depending on timing and context.

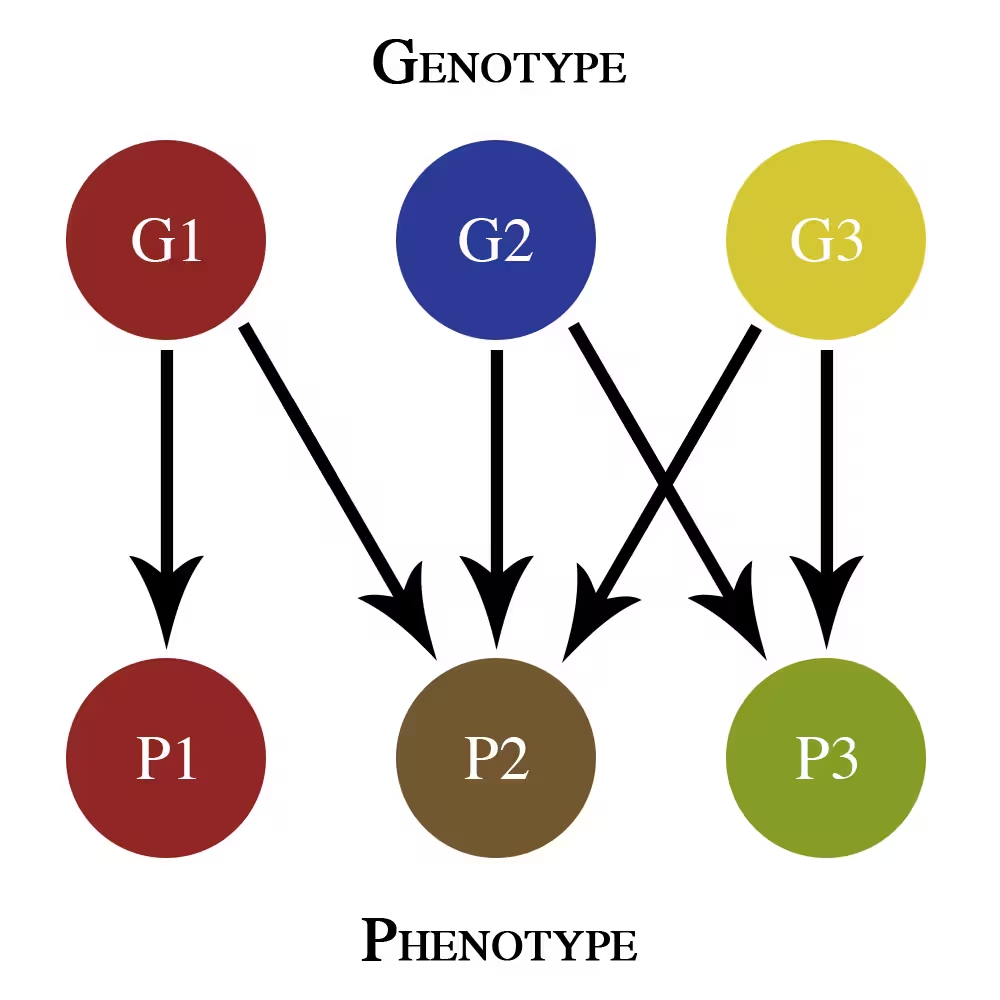

This simple genotype-phenotype map only shows additive pleiotropy effects. G1, G2, and G3 are different genes that contribute to phenotypic traits P1, P2, and P3.

Why this finding could change treatment strategies

Understanding the shared genetic architecture shifts how scientists think about diagnosis and therapy. "Pleiotropy was traditionally viewed as a challenge because it complicates the classification of psychiatric disorders," Won said. "However, if we can understand the genetic basis of pleiotropy, it might allow us to develop treatments targeting these shared genetic factors, which could then help treat multiple psychiatric disorders with a common therapy."

The public-health stakes are high: the World Health Organization estimates roughly one in eight people—almost a billion worldwide—live with some form of psychiatric condition. Therapies that target central nodes in protein networks or regulatory cascades could, in theory, reduce symptom burden across diagnostic categories instead of treating each disorder in isolation.

Beyond therapeutics, the study provides a roadmap for future work: prioritize pleiotropic regulatory variants, map their temporal activity in the developing brain, and test whether intervening on shared pathways alters risk for several disorders at once. Published in Cell, this research is an important step toward that integrated approach.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment