10 Minutes

Imagine a world with two suns rising and setting across a sky unlike ours. It’s a vivid image—Tatooine, the archetype of the two-star planet—and yet real, observable examples are puzzlingly scarce. Astronomers expected to find many circumbinary planets circling tight pairs of stars, but the catalog of confirmed two‑sun worlds remains thin. Why do so few planets survive close to compact binary stars?

When Newton Meets Einstein: the missing planets problem

The conventional explanation for planetary orbits starts with Newtonian gravity: the pull between masses shapes orbital paths, and small perturbations change those paths slowly. Planet formation models suggest that most stars—single or paired—should develop planetary systems. Observationally, missions like Kepler and TESS have discovered thousands of exoplanets, yet only a tiny fraction orbit binary stars. Out of more than 6,000 confirmed exoplanets, astronomers have validated only a handful that circle both members of a stellar pair.

There’s an added oddity: tight binaries—pairs of stars orbiting each other in days—are especially barren. Surveys have identified thousands of eclipsing binary systems where transits should make circumbinary planets easiest to detect, and yet the expected yield never materialized. The lack of close-in circumbinary planets is not merely an observational glitch. It points to a dynamical process that removes those worlds over time.

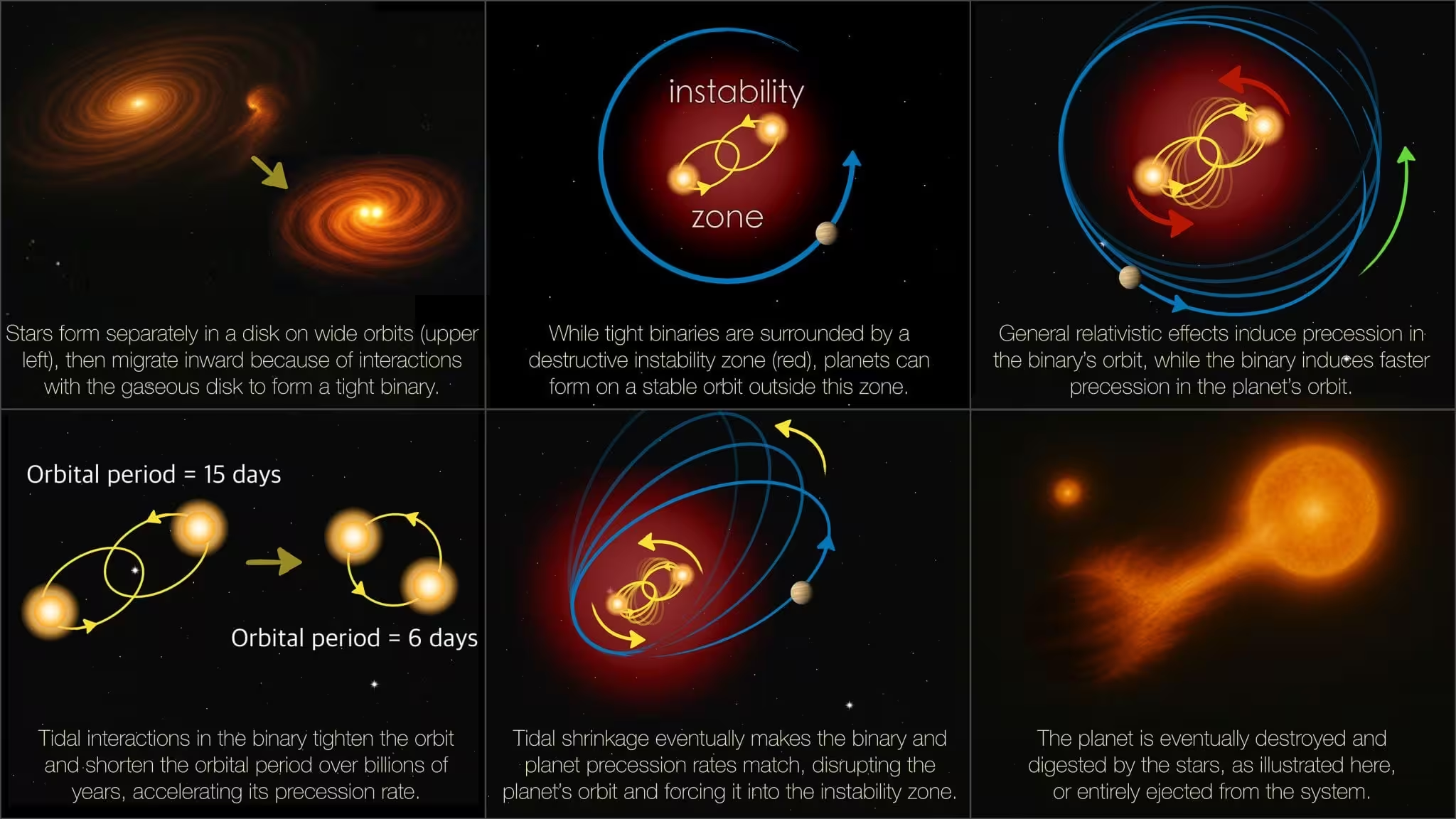

Part of the answer lies in orbital precession. A planet orbiting two stars does not keep the same ellipse forever; its orbit slowly rotates, or precesses, because the gravitational tug of the two stars changes direction over time. The binary stars themselves also precess, but for a different reason: relativistic corrections to gravity—effects predicted by Einstein—become non-negligible when the stars are massive and orbit each other tightly.

Resonance and the slow destabilization of circumbinary orbits

General relativity alters how the binary’s closest approach (periastron) shifts with each orbit. As the stellar pair tightens—by interactions with gas early on and by tidal friction over long epochs—the rate at which the binary’s periastron advances increases. At the same time, a circumbinary planet’s precession rate, driven by the Newtonian tug of the two stars, tends to slow as the stars draw closer. When these two precession rates converge, they can lock into a resonance.

Resonance is a simple but powerful concept: two oscillations sharing the same rhythm can amplify each other. For a circumbinary planet, entering a resonance with the binary means its orbit is gradually stretched into more eccentric shapes. One moment the planet swings much farther out; the next, it plunges closer to the stars. Once periastron of the planet overlaps a region of dynamical instability around the binary, one of two fates usually follows: ejection or destruction.

In ejection, three‑body gravitational interactions give the planet a kick sufficient to send it into a distant orbit or entirely unbound from the system. In destruction, the planet’s periastron becomes so tight that tidal forces or direct collision with a star shred or engulf it. These transformations can occur over tens of millions of years—rapid compared with stellar lifetimes—so by the time we observe many tight binaries, any close-in planets that originally existed have already been removed.

Mohammad Farhat, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, who led recent theoretical work on this topic, explains it plainly: a planet in resonance can be gradually pumped to higher eccentricity until it either gets flung away or torn apart. Jihad Touma, a co-author from the American University of Beirut, adds that this is not an exotic, contrived process; it is a natural outcome of combining Newtonian orbital dynamics with relativistic corrections when binaries tighten to periods of about a week or less.

Why detection methods miss the survivors

Survival, when it occurs, tends to favor distance. Planets that avoid resonance simply sit far enough from the binary that the resonant interaction never becomes strong. Those distant circumbinary planets are real, but they are harder to spot. Transit surveys like Kepler and TESS detect planets by the slight dimming they cause when passing in front of their host stars. A wide-orbit planet has a much lower geometric probability of transiting from our vantage point and a correspondingly smaller chance of being recorded during a fixed-duration survey.

Kepler cataloged roughly 3,000 eclipsing binaries—systems in which the orbital plane lines up with our line of sight so that stars eclipse each other. If a significant fraction of those binaries hosted large planets, transits would likely appear in the data. Instead, researchers identified far fewer candidates than predicted, and most confirmed circumbinary planets sit just outside the inner instability zone. That clustering suggests migration: planets may form farther out in the protoplanetary disk and slowly drift inward until halted at the stability boundary. Forming a planet directly at the instability edge would be like trying to stack fragile bricks in a storm; collisions between planetesimals are too violent to let growth proceed efficiently.

The upshot is a detection bias layered on top of a destructive dynamical mechanism. The combination creates what researchers call a circumbinary planet "desert" close to tight binaries. Observationally, this desert shows up as an absence of confirmed planets around binaries with orbital periods shorter than roughly seven days.

Instability zones, formation theory, and simulation results

Detailed numerical simulations and analytic calculations support this picture. When relativistic precession of the binary is included, the fraction of planets destabilized around tight binaries becomes substantial. Theoretical models suggest that roughly 80% of planets near such binaries can be disrupted over the system’s evolution, and about three‑quarters of those are destroyed outright rather than simply sent into wide, cold orbits. These are not fringes of parameter space; they are the dominant outcomes for many initial configurations.

Why does relativity matter here more than in typical exoplanetary problems? Because relativistic corrections scale with the compactness and speed of the orbiting masses. Mercury offered the canonical example in our solar system: Newtonian gravity left a small, unexplained precession of Mercury’s perihelion, and Einstein’s theory supplied the correction. In tightly bound stellar binaries, where masses are larger and orbital speeds higher, the relativistic precession can dominate the binary’s evolution and shift resonant interactions into regimes where planet survival becomes precarious.

These findings also shed light on why multiple planets are rare near tight binaries. A resonance that destabilizes one planet will likely affect nearby companions, sweeping through a range of orbital radii and removing several potential planets in succession. Thus the observed paucity of circumbinary systems with compact stellar pairs does not imply that planet formation failed; rather, it implies that long-term dynamical survival is difficult under the combined action of tides, migration, and relativistic resonance.

Expert Insight

"When you let general relativity into the long game, the picture changes in ways you wouldn’t guess from Newton alone," says a fictional senior astrophysicist speaking for context. "Relativity speeds up the binary’s precession, tides and migration change the geometry, and the planet’s orbit is squeezed into resonant traps. The result is a natural pruning of worlds near the tightest binaries."

Another voice from the theoretical community notes: "This mechanism helps reconcile simulations of planet formation—with planets forming commonly—with the observational fact that we rarely see circumbinary planets in tight systems. Many formed, but most didn’t survive long enough to be photographed by our surveys."

Broader implications and future directions

The interplay between relativity and orbital dynamics has consequences beyond circumbinary exoplanets. Researchers are exploring whether similar resonant processes affect planets orbiting compact objects—binary pulsars or stars orbiting pairs of supermassive black holes at galactic centers. Where masses are extreme and orbital timescales short, relativistic precession can dominate the secular evolution of surrounding bodies, changing how we interpret long-term stability.

On the observational side, the work implies specific strategies. If circumbinary planets survive mostly at wider separations, surveys that can detect longer‑period transits or that use direct imaging and astrometry may find the missing population. Next‑generation instruments and longer baseline observations will be key. Meanwhile, models that combine hydrodynamics of planet formation with long-term relativistic dynamics will refine where survivors are most likely to be found.

There’s also a broader reminder here about the layered complexity of astrophysical systems. Processes that seem subtle on short timescales—relativistic precession, tidal migration—can, given millions or billions of years, sculpt entire planetary populations. Einstein’s corrections, introduced a century ago, remain relevant and sometimes decisive in modern exoplanetary science.

Observationally, the scarcity of two-sun worlds close to tight binaries is no longer merely an odd statistic. It is a natural consequence of resonant dynamics seeded by relativistic effects and nurtured by tides and migration. The universe has a way of quietly erasing certain possibilities—fast, efficient, and indifferent to our expectations.

As telescopes improve and surveys extend their time baselines, we should expect to find more distant circumbinary planets, and with them a fuller accounting of how planets form and vanish in the shadow of two suns.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

max_x

Solid theory, but feels a bit neat; sims hinge on messy disk physics and migration. if resonance is that brutal why not a couple odd survivors?

astroset

is this even true? sounds plausible but where are the numbers, like detection limits, inclinations, survey durations. feels like more to unpack

atomwave

wow didn't expect relativity to evict planets, lol. imagining two suns then physics quietly erases them… kinda poetic, kinda brutal

Leave a Comment