10 Minutes

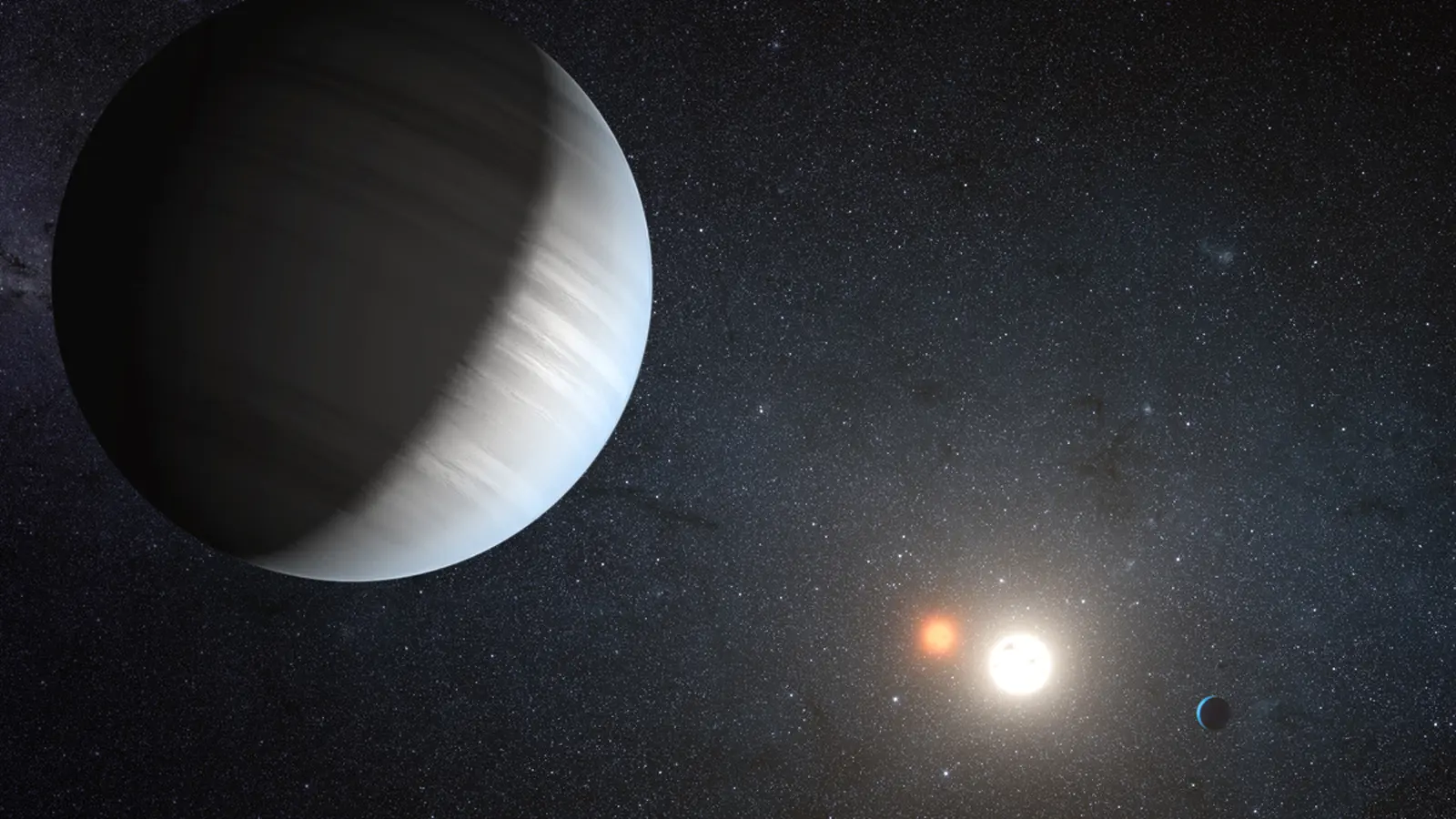

Astronomers have found and directly imaged a massive exoplanet that orbits two suns — a real-life echo of the fictional Tatooine. Discovered in archival data and confirmed independently by a European team, this circumbinary world pushes the limits of what we know about planet formation in complex, multi-star environments.

Scientists first noticed the faint object in years-old observations taken with the Gemini Planet Imager (GPI). After careful analysis and cross-checks with data from the W.M. Keck Observatory, the team at Northwestern University confirmed the candidate is a planet roughly six times the mass of Jupiter, roughly 13 million years old, and about 446 light-years from Earth.

How a hidden planet emerged from archival data

The discovery reads like a detective story in observational astronomy: no new telescope was required, only fresh eyes on existing images. Jason Wang, an assistant professor of physics and astronomy at Northwestern University and one of the study’s senior authors, led a team that re-examined data from the Gemini Planet Imager — an instrument designed to suppress starlight and reveal faint planetary companions.

GPI uses adaptive optics to correct for atmospheric blurring and a coronagraph to block a star’s glare. During its years at the Gemini South telescope in Chile, the instrument observed hundreds of nearby stars searching for planets. The GPI Exoplanet Survey produced a trove of images, many of which have become valuable archives for reanalysis as image-processing techniques and scientific questions evolve.

“We undertook this big survey, and I traveled to Chile several times,” Wang said. “I spent most of my time during my Ph.D. just looking for planets. During the instrument’s lifetime, we observed more than 500 stars and found only one new planet. It would have been nice to have seen more, but it did tell us something about just how rare exoplanets are.”

Nathalie Jones, the study’s lead author and a CIERA graduate fellow, combed through GPI data taken between 2016 and 2019 and matched faint detections against Keck observations. When she noticed a dim object that moved in lockstep with one of the stars — a telltale sign that it was gravitationally bound rather than a background star — the team began to suspect they had found a planet.

Imaging a planet that orbits a tight binary

Directly imaging an exoplanet is already difficult because stars can outshine their planets by millions to billions of times. Doing so in a binary system adds complexity: two stars produce combined glare and dynamic gravitational fields.

What makes this discovery unusual is how close the planet lies relative to its binary host compared with other directly imaged circumbinary planets. The two stars in the system orbit each other extremely tightly — completing a mutual orbit every 18 Earth days — while the planet circles both of them on a much longer, 300-year trajectory. That places the planet far enough to be a circumbinary object, but significantly nearer to its suns than most directly imaged planets in similar systems.

Planet properties: massive, young, and still warm

The planet is roughly six times the mass of Jupiter, placing it in the regime of gas giants and, depending on formation details, possibly near the border between massive planets and brown dwarfs. At an estimated age of about 13 million years, it is extremely young by planetary standards and still retains significant heat from its formation. That residual heat makes young giant planets brighter in infrared light, aiding direct-detection surveys.

Located about 446 light-years from Earth, the system is not in our immediate stellar neighborhood but is close enough for detailed follow-up with large telescopes. Spectral analysis of the planet’s light — which Jones and colleagues used to distinguish it from background stars — suggests temperatures higher than any world in our solar system yet cooler than many other directly imaged exoplanets.

Because the planet formed relatively recently in cosmic terms (about 13 million years ago — roughly 50 million years after the dinosaurs went extinct), it still radiates formation heat. That makes it an attractive target for studies of atmospheric composition, thermal structure, and early planet evolution.

Why this discovery matters for planet formation theories

Most exoplanets discovered to date orbit single stars. Binary and multiple-star systems present different challenges and pathways for planet formation because of more complex gravitational dynamics, disk truncation, and potential perturbations during the planet-building phase.

Finding a massive, young planet orbiting a tight binary adds a critical datapoint. It shows that giant planets can survive — and possibly form — in the presence of close stellar pairs. One hypothesis is that the binary stars formed first and that the planet subsequently formed in a circumbinary disk around both stars. Another possibility is that dynamical interactions or migration moved the planet to its current orbit after formation.

“Because we have only detected a few dozen planets like this, we don’t have enough data yet to put the picture together,” Wang said. Continued monitoring will be essential to trace orbital motion and constrain models of how such systems assemble.

Follow-up plans and technological context

The discovery highlights the scientific value of archival datasets and the long tail of discoveries they can enable. As instruments and image-processing methods improve, more planets may be hiding in plain sight within older observations.

GPI itself is being upgraded and will soon move to the Gemini North telescope on Mauna Kea in Hawaii. Improved adaptive optics and coronagraphy, along with longer time baselines and more sensitive detectors, will boost astronomers’ ability to image faint companions in binary systems.

The Northwestern team plans continued monitoring of the circumbinary planet and its host stars. By tracking the sky positions of the two stars and the planet over years and decades, researchers aim to directly map the three-body dynamics in the plane of the sky. Those measurements will feed into tests of formation and migration theories and refine system mass estimates that depend on orbital motion.

Scientific context: circumbinary planets and direct imaging

Circumbinary planets — those that orbit two stars — are not purely fictional. Kepler and TESS have found numerous transiting circumbinary planets by detecting the periodic dimming of the combined stellar light. However, transit surveys are biased toward planets with orbits that cross our line of sight; direct imaging complements transit and radial-velocity methods by revealing widely separated, self-luminous young giants that would not otherwise be detected.

Direct imaging is particularly sensitive to young, massive planets because they emit more infrared radiation from residual formation heat. Instruments like GPI, SPHERE on the Very Large Telescope, and upcoming facilities (e.g., the James Webb Space Telescope’s coronagraphic modes, next-generation extremely large telescopes) will expand the census of such objects and probe their atmospheres in detail.

Expert Insight

Dr. Laura Chen, an astrophysicist who works on exoplanet formation (not involved in the study), commented: “This detection is exciting because it occupies a parameter space where theory has been uncertain. Tight stellar binaries present a hostile environment to planet formation, yet here we see a massive planet surviving in a relatively close circumbinary configuration. Continued astrometric monitoring will be essential to untangle whether this planet formed in place, migrated inward, or was sculpted by dynamical interactions early in the system’s history.”

“Direct imaging of planets is challenging, but it provides a unique window on young planetary atmospheres,” Dr. Chen added. “Combining imaging with spectroscopy and long-term orbital tracking is the best way to constrain composition, mass, and formation scenarios.”

What astronomers will watch next

Jones and colleagues are preparing proposals to secure more telescope time to monitor both the planet and the binary. Key aims include measuring orbital motion precisely enough to determine system masses dynamically, obtaining higher signal-to-noise spectra to search for molecules such as water and methane in the planet’s atmosphere, and searching archival images for additional, fainter companions.

Independent confirmation of the discovery by a European team at the University of Exeter, published in Astronomy and Astrophysics, strengthens confidence in the result and underscores the collaborative, reproducible nature of modern observational astronomy.

Finally, this detection serves as a reminder: archives hold surprises. As instruments are upgraded and analytic techniques mature, revisiting old data can produce new discoveries. Nathalie Jones continues to comb GPI’s archive for other overlooked objects — and she’s found a few suspicious candidates that warrant further study.

“I’m asking for more telescope time, so we can continue looking at this planet,” Jones said. “We want to track the planet and monitor its orbit, as well as the orbit of the binary stars, so we can learn more about the interactions between binary stars and planets.”

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

Marius

Feels a bit overhyped but cool find. Archives FTW, still need more orbital data tho to know formation.

astroset

is this even true? Six Jupiters, 13 Myr, sounds like a borderline brown dwarf, could spectra be misleading, or am I missing something

atomwave

Wow didn’t expect a Tatooine in real life! Young, massive and orbiting two suns, that's cosmic drama. Hope they keep watching curious if it migrated or formed there…

Leave a Comment