5 Minutes

Imagine your brain drifting a few millimetres inside your skull. It sounds like science fiction, but recent MRI analyses of astronauts show that microgravity can nudge the brain upward and backward, subtly reshaping how it sits within the skull. Small movement. Big implications.

How the brain moves in microgravity

On Earth, gravity is a constant sculptor: it pulls blood and cerebrospinal fluid downward, helping the brain, fluid and soft tissues find a steady equilibrium. In orbit that sculptor disappears. Fluids shift toward the head. Faces puff. The whole internal balance changes and the brain effectively floats within a confined, bony chamber.

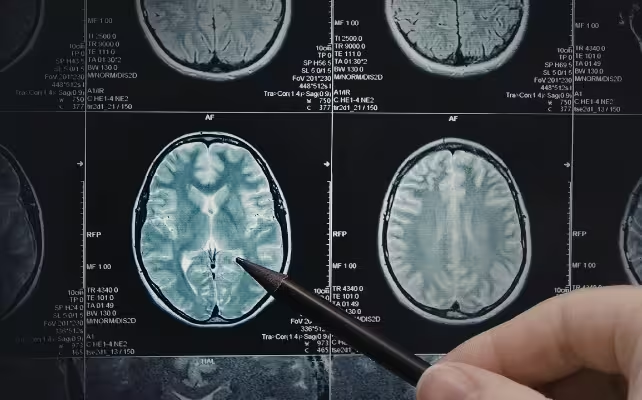

To see precisely how that floating plays out, researchers compared magnetic resonance scans taken before and after spaceflight from 26 crew members who spent anywhere from a few weeks to more than a year off-world. Rather than treating the brain as a single mass, the team aligned each astronaut’s skull across scans and mapped movement in more than 100 discrete brain regions. That detail made patterns visible that average whole-brain measures had obscured.

The result: a consistent pattern of upward and backward shifts after flight. Longer missions produced larger displacements. In some astronauts who spent approximately a year aboard the International Space Station, certain cortical areas near the top of the brain moved upward by more than 2 millimetres while other regions hardly budged. Two millimetres may seem trivial. Inside the compact architecture of the skull, it is not.

Regions tied to sensation and movement showed the largest shifts. Structures on the left and right sides of the brain drifted toward the midline in opposite directions for each hemisphere; those mirror-image changes cancel out in a whole-brain average, which helps explain why earlier, cruder analyses missed them entirely. Most changes and deformations trended back toward baseline within about six months after return, but the backward displacement recovered more slowly than the upward shift. Gravity pulls downward, not forward, and that asymmetry may underlie the uneven recovery.

Why this matters for long missions and space travelers

What should we make of a brain that shifts its position by a few millimetres? First: measured movement does not translate directly into immediate illness. Crewmembers in the study did not report clear symptoms tied to these positional shifts — no widespread headaches or fog — even though larger displacements in sensory-processing regions correlated with measurable postflight balance changes in some individuals. Second: as missions lengthen under programs like Artemis and commercial spaceflight expands, subtle anatomical shifts take on new importance. Cumulative exposure, repeated flights, and travel by people who are not career astronauts could change the risk profile.

Understanding the mechanics matters for practical reasons. If microgravity nudges fluid and soft tissue in predictable ways, engineers and medics can design countermeasures: refined exercise protocols, suit and habitat designs that manage fluid distribution, or medical monitoring targeted to those brain regions most at risk. The study’s methodological advance — aligning skulls and tracking many regions rather than averaging the whole brain — provides a sharper map of where interventions should focus.

There are unanswered questions. How do repeated long-duration flights accumulate risk? Do age, sex, or preexisting conditions influence the magnitude or recovery of shifts? And what happens to intracranial pressure dynamics over months or years in partial-gravity environments, like the Moon or Mars?

What the findings do provide is a direction. They do not argue against space travel; instead, they give mission planners data they can act on. Better monitoring, targeted rehabilitation after return, and designing habitats that mitigate fluid redistribution are all within reach. The brain may move a little. But knowing how it moves is the first step toward keeping astronauts healthy.

As humanity steps farther from Earth, the skull becomes not just a container but a living landscape that changes with the journey. Will our countermeasures keep pace with exploration? The answer will shape the next chapter of human spaceflight.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

DaNix

is this even real or MRI artifact? 2 mm seems tiny but maybe big for function. did crews actually feel it? curious about age/sex differences and repeated flights, need more data

astroset

wow ok this is wild. the brain literally shifts mm in the skull? kinda spooky. hope they nail countermeasures, cuz repeated missions could matter. quick thought: what about older travelers and cumulative effects..

Leave a Comment