4 Minutes

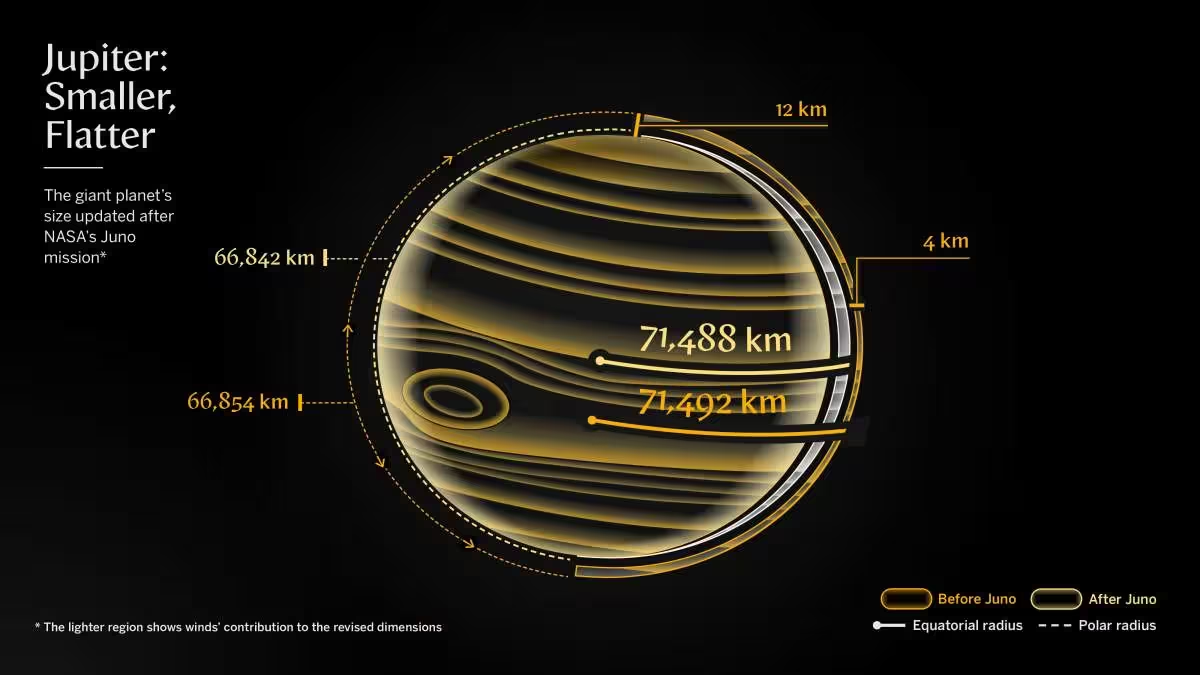

New analyses of radio signals passing behind the planet reveal that the gas giant's equatorial radius is 71,488 kilometers (44,421 miles), while its polar radius reaches 66,842 kilometers from center to north pole. Those numbers trim roughly 4 kilometers from each side at the equator and about 12 kilometers off each pole compared with long-standing values derived from 1970s spacecraft data. A few kilometers in a planet the size of Jupiter sounds like nitpicking. In planetary science, it can be a game changer.

How a handful of kilometers refines our picture

Measurements matter because models are sensitive. Shift the boundary by even a small margin and the inferred distribution of mass, temperature, and winds inside the planet can change in meaningful ways. "These few kilometers matter," says Eli Galanti, a planetary scientist at the Weizmann Institute of Science. "Shifting the radius by just a little lets our models of Jupiter's interior fit both the gravity data and atmospheric measurements much better."

The technique behind the update is radio occultation (RO). When a spacecraft passes behind a planet from Earth's perspective, radio signals transmitted through the planet's atmosphere get bent. The amount and character of that bending encode density and temperature profiles high in the atmosphere. Voyager and Pioneer provided only six such occultation cuts in the 1970s, limiting the fidelity of earlier measurements. Juno changed that.

In 2021 NASA nudged Juno into an orbit that regularly carries the probe behind Jupiter relative to Earth. That alignment allowed repeated RO observations. Paired with more advanced signal-processing methods, the new dataset delivers far denser sampling of atmospheric refraction than previous missions could. "We tracked how the radio signals bend as they pass through Jupiter's atmosphere, which allowed us to translate this information into detailed maps of Jupiter's temperature and density, producing the clearest picture yet of the giant planet's size and shape," explains Maria Smirnova, a planetary scientist at the Weizmann Institute.

There is another wrinkle: winds. Jupiter's fast rotation drives powerful zonal jets, which perturb the atmospheric shape. Earlier size estimates generally treated the atmosphere as if winds were negligible. With modern wind analyses available from other measurements, Galanti and colleagues incorporated atmospheric dynamics into their calculations. The result is a radius estimate that better reconciles gravity field data, wind profiles, and atmospheric structure.

Why should anyone beyond planetary scientists care? For one, precise radii matter when comparing Jupiter to other gas giants — both inside our Solar System and around other stars. Small changes in size propagate into calculations of internal composition, core mass, and heat transport. That in turn affects theories about how gas giants form and evolve. For exoplanet hunters, better benchmarks here at home improve the inference tools used to interpret distant worlds.

Technically, the work appears in Nature Astronomy and represents an incremental but important refinement rather than a dramatic rewrite. It’s a reminder that exploration continues to pay dividends even for the best-known planets: new trajectories, better processing, and a willingness to fold in messy details like winds can yield clearer answers.

Science advances in the margins. A few kilometers can sharpen the portrait of a planet and open new lines of inquiry about how giants live and breathe in our universe.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment