7 Minutes

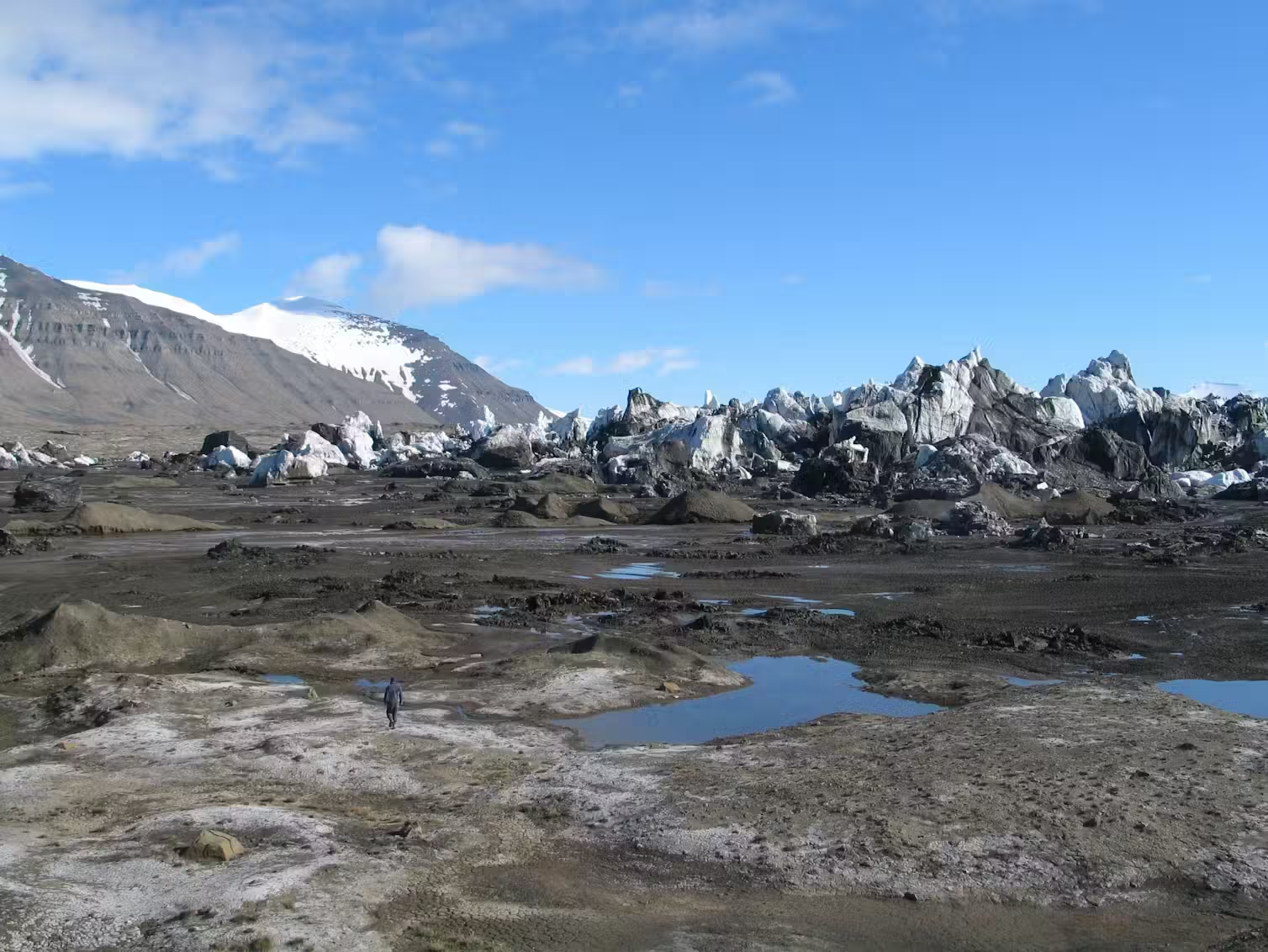

I once stood less than a kilometer from an ice face that was literally gaining ground. The sound was a constant, low thunder—cracks, groans, slabs of ice collapsing—and overnight the slope I had walked the day before seemed closer. Surges can be like that: sudden, relentless, and strangely fast for something measured in centuries.

The surprising speed of glacier surges

Not all glaciers behave the same. Most retreat quietly as climate warms, shrinking year after year. A minority, however, do the opposite. They switch modes and accelerate from a sleepy crawl to tens of metres per day. Sometimes they peak at more than 60 metres a day, sustaining that furious pace for months or even years. It is a violent change of tempo—a glacier that felt stationary on Monday can be a moving hazard by Friday.

Scientists call this phenomenon glacier surging. It is not the steady flow of ice under gravity that glaciologists teach in textbooks; it is a transient state, typically initiated by processes at the glacier bed. Meltwater, trapped beneath the ice, behaves like hydraulic oil. It reduces friction and allows vast slabs of ice to slip forward. When the subglacial plumbing eventually clears and the water drains away, the glacier can brake hard and slow down, sometimes over days, sometimes across seasons.

Nathorstbreen in Svalbard provides a dramatic example. From 2008 it surged, advancing more than 15 kilometres in roughly a decade. Terrain maps were rewritten. River courses shifted. Land that had seemed permanent was not.

Surging glaciers in the Panmah region of the Karakoram, High Mountain Asia.

Where surges are clustered — and why that matters

We recently catalogued over 3,000 glaciers that have surged at least once. That number represents only about 1% of global glaciers, but because surging glaciers tend to be large, they account for roughly 16% of global glacier area. They are not scattered randomly. Instead, surging glaciers cluster in a handful of regions: parts of the Arctic, the Karakoram and other high mountains of Asia, and the Andes. They are rare in places that are either too warm—think the European Alps—or too cold and dry, like much of Antarctica.

Climate sets the stage, but geology and glacier size write the script. Thick ice over deformable sediments encourages surging; so does a climate that produces just enough melt to lubricate the bed without sustaining continuous high runoff that would keep the glacier sliding at a steady pace.

Why should anyone care? Because surges are not merely a geological curiosity. They can be hazardous. Advancing ice can overrun roads and farms, bury infrastructure, and dam rivers to form unstable lakes. When those ice-dammed lakes fail, floods can travel downstream with catastrophic force. The Karakoram region has repeatedly seen this pattern. The Shisper Glacier, for example, created a lake that drained multiple times between 2019 and 2022, repeatedly damaging the Karakoram Highway, a vital link between Pakistan and China.

Fast-moving ice also strains human mobility. In Svalbard and similar places, glaciers are highways in winter; sudden crevassing during a surge can cut access to remote communities and climbing routes. When surging glaciers hit the sea, they can shed large numbers of icebergs in a short period, complicating shipping and tourism.

Surging glaciers demonstrate that ice does not respond to warming in a simple linear way. Some glaciers thin and lose the capacity to surge. Others, paradoxically, surge more often as changing weather patterns deliver bursts of melt or intense rainfall that trigger early surges.

How climate change is rewriting surge behaviour

There is no single trend. In some regions surges have become less frequent as glaciers lose mass; in others, they are becoming more unpredictable, appearing earlier or lasting for different lengths of time than historical records suggest. Extreme weather is a new wildcard. A few heavy rainstorms or an anomalously warm season can change the subglacial water regime and precipitate a surge. That means places that did not historically host surging glaciers could begin to experience them as the atmosphere heats and the hydrological cycle intensifies.

Consider the Antarctic Peninsula, which is warming rapidly: areas once too cold and dry to sustain the kind of meltwater systems that drive surges might start to develop them. The result would be a suite of new hazards in regions where communities and infrastructure are ill-prepared for sudden glacier motion.

Scientific context and implications

Understanding surges requires observations at multiple scales. Satellite time series reveal the timing and magnitude of accelerations; fieldwork probes the bed and measures water pressure; numerical models test how subglacial drainage networks evolve. Each approach fills a blind spot left by the others.

From a risk-management perspective, the research has practical value. Early-warning systems for ice-dammed lakes, route planning that accounts for potential crevasse outbreaks, and infrastructure siting that avoids likely surge paths are all tangible outcomes of improved surge science. For communities downstream, the ability to predict which advance will lead to a dam and which will not can mean the difference between benign change and disaster.

Expert Insight

"Surging glaciers are a reminder that the cryosphere can surprise us," says Dr. Mira Patel, a glaciologist at the University of Leeds. "We used to think surges were rare curiosities; now we see they can reshape landscapes and lives. Better monitoring—satellite, airborne, and on the ground—is the only way to move from reactive to proactive management."

Research methods and future prospects

Large-scale inventories combine historical maps, satellite imagery and field reports to spot past surges. Machine learning tools help detect abrupt changes in velocity from decades of satellite data. Yet important questions remain: what sets the recurrence interval of a surging glacier, how will changing precipitation patterns alter the subglacial plumbing, and which regions will flip from quiet to active as the climate evolves?

Technologies such as interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR) and high-resolution optical time series are improving detection of rapid accelerations. Coupling those remote-sensing tools with targeted field campaigns that measure bed composition and water pressure will be crucial. The goal is not merely academic. It is to provide actionable information to communities living in the shadow of surging ice.

Surges teach a broader lesson: the cryosphere is neither uniformly fragile nor uniformly resilient. It contains dynamic systems that can accelerate without warning, amplify local hazards, and defy simple predictions. Preparing for that unpredictability is a practical necessity for anyone who lives downstream or designs roads, bridges, and settlements near ice.

Surging glaciers are one of nature's sharper reminders that in a warming world, change can be sudden—and often, it arrives from below.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

labcore

Wow, that bit about ice gaining ground gave me chills. The speed, the noise, rivers rerouted.. makes you rethink 'stable' landscapes. Scary but fascinating

Leave a Comment