6 Minutes

Scientists are rethinking the point at which cancer begins to matter. Instead of reacting after symptoms force a diagnosis, research groups are chasing the disease back along its timeline — years, even decades, before a tumour becomes obvious.

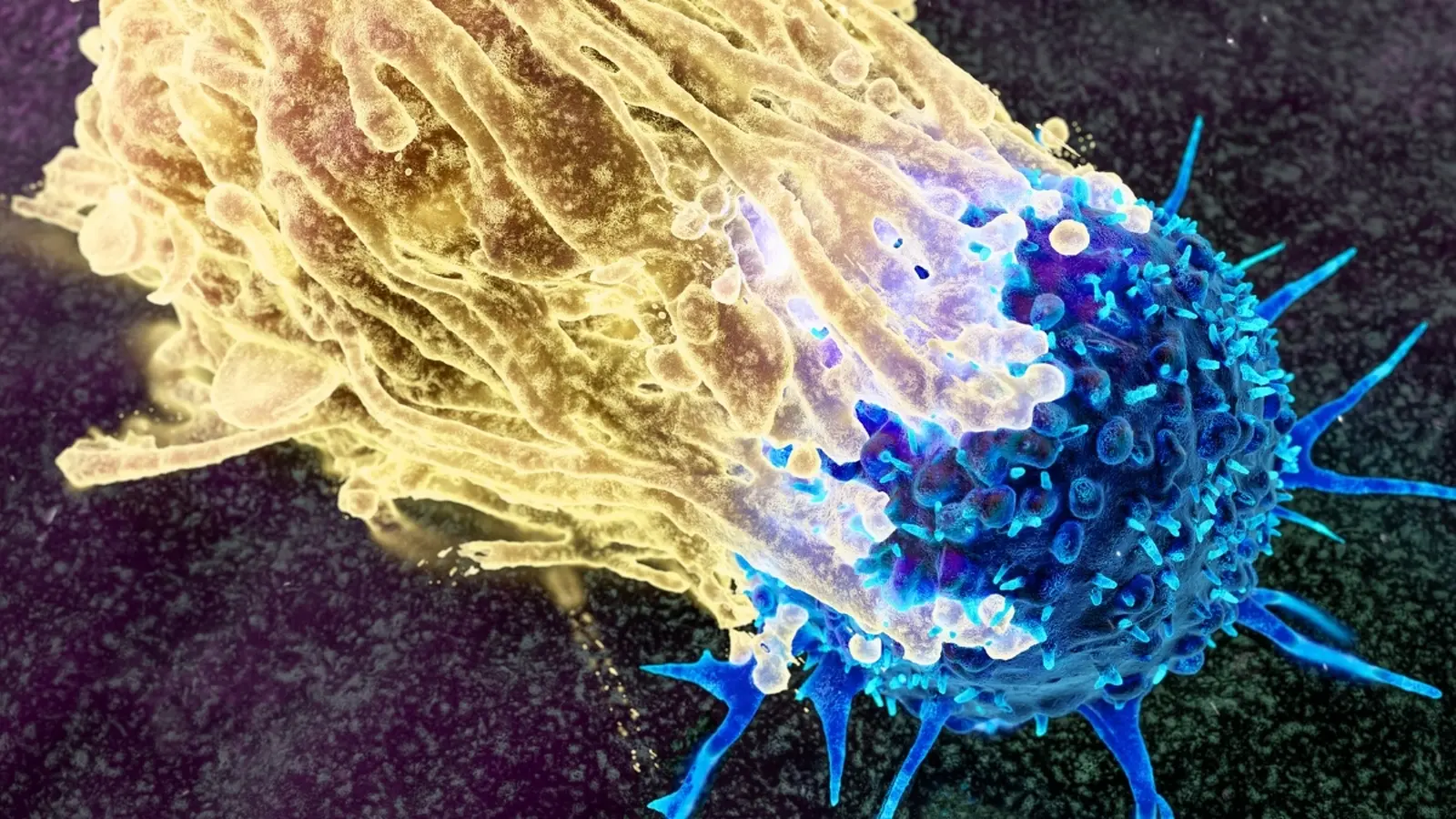

Think of cancer not as a sudden storm but as weather patterns that, over time, shape the landscape. Small changes accumulate. Cells pick up mutations. Tiny populations of altered cells expand or fade. Some lesions sit quietly for years. Others shift and grow under the influence of genes, inflammation, and our environment. Detecting those patterns early is the heart of a movement called cancer interception.

Scientists are now exploring a radical shift in how we tackle cancer.

Tracing the first missteps: what the biology reveals

Large genetic studies and long-running cohorts have upended the idea that tumours arrive fully formed. Instead, a stepwise process unfolds at the cellular level. With age, many tissues accumulate clones — small groups of cells carrying the same mutation. In blood, this phenomenon is well described: clonal expansions can signal an elevated risk of blood cancers such as leukaemia. The same dynamic — albeit less studied — appears in skin, lung, colon and other organs.

One long-term study that tracked roughly 7,000 women over 16 years showed how different mutations influence clone behaviour. Some mutations give cells a replicative edge. Others make them unusually responsive to inflammation. When an inflammatory flare occurs, clones that are inflammation‑sensitive can swell, changing the risk landscape for that person.

That matters because it makes risk measurable. By sequencing DNA from blood samples or biopsies, clinicians can quantify these clones and watch their trajectory. The measurements don’t diagnose cancer; they reveal a probabilistic elevation in risk. But probability, when tracked over years, becomes actionable.

Tools for early detection: from ctDNA to multi-cancer tests

New blood-based tests look for fragments of tumour DNA — circulating tumour DNA, or ctDNA — that cancers and some precancerous lesions shed into the bloodstream. Multi-cancer early detection tests (MCEDs) scan for patterns of ctDNA that suggest the presence of malignancy somewhere in the body. Early results are promising: when cancer is found at stage I, survival rates for several tumour types, notably colorectal cancer, improve dramatically compared with detection at advanced stages.

Yet MCEDs are not perfect. They can miss cancers and they can flag signals that do not correspond to a clinically significant tumour. A positive result usually requires follow-up imaging, targeted biopsies and careful clinical interpretation. False positives introduce anxiety, additional procedures and costs. False negatives, meanwhile, offer false reassurance. The challenge is to tune sensitivity and specificity so that benefits outweigh harms across diverse populations.

Researchers envision a risk model similar to cardiology’s: instead of waiting for a heart attack, clinicians assess a patient’s risk profile and prescribe preventive measures years in advance. For cancer, the pedigree would combine genetic markers, environmental exposures, inflammatory history, and MCED output to estimate future risk and guide interventions. But cancer is more varied than heart disease. Some early lesions regress. Others progress unpredictably. Unlike statins — a broadly effective preventive drug for many at‑risk people — cancer prevention will often be more individualized.

Ethics, equity and the cost of early knowledge

As detection tools mature, difficult ethical questions arise. Who should be tested? When does knowledge help, and when does it simply create worry? A person told they harbour high‑risk clones may feel compelled to undergo invasive procedures for a condition that might never progress. Older adults present another dilemma: benefits shrink and harms can multiply, yet both patients and clinicians tend to overestimate potential gains.

Access is a second concern. If MCEDs and deep sequencing live behind private paywalls, health inequities will widen, especially in low‑ and middle‑income countries. Regulators are already scrutinizing the tests. In the United States, agencies are evaluating how accurate MCEDs must be and what follow-up pathways should look like. The UK’s National Cancer Plan has committed to expanding diagnostic capacity and to use ctDNA biomarker testing in lung and breast cancer, with plans to broaden use where cost‑effectiveness is demonstrated.

Balancing the promise of early interception with the risk of harm demands robust evidence from randomized trials, transparent public discussion, and careful policy design. Purely technological advances will not solve socio‑ethical problems; deployment strategies will.

Expert Insight

"Detecting a signal is only the first step," says Dr. Eleanor Price, a medical oncologist who studies cancer prevention. "We need validated decision pathways so clinicians know what to do when a test lights up. That means trials that compare watchful waiting, targeted prevention, and early treatment, and it means thinking hard about patient preferences."

Dr. Price’s point underlines a simple truth: technology can detect risk, but medicine must translate risk into care that improves lives.

Where this could take us

Looking ahead, cancer interception could change oncology the way vaccines changed infectious disease: fewer emergencies, more prevention. Practical steps will include refining MCED accuracy, defining which biomarkers truly predict progression, and building equitable screening programs that reach underserved populations. Integration with electronic health records, cost‑effectiveness analyses, and clinician training will be essential.

For patients, the prospect is both hopeful and complicated. The opportunity to spare lives and reduce late‑stage suffering is real. The route there will require scientific rigour, clear communication, and a commitment to fairness. If we can learn to read cancer’s earliest signals without amplifying fear or inequity, we may finally begin to stop many cancers before they start, rather than only treating them after the storm has arrived.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment