5 Minutes

Depression showed up years before movement problems. And it kept coming afterward. That pattern emerges from a large Danish registry study led by clinician-scientist Christopher Rohde and colleagues at Aarhus University. By comparing people who later developed Parkinson’s disease or Lewy body dementia with patients living with other serious chronic illnesses, the team sought to untangle whether mood changes are a specific early alarm for neurodegeneration—or simply a reaction to long-term illness.

What the records revealed

The investigators tracked health data from 2007 to 2019 and identified 17,711 individuals who received a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease or Lewy body dementia during that interval. Those cases were matched against large comparison groups: 19,556 people with rheumatoid arthritis, 40,842 with chronic kidney disease, and 47,809 with osteoporosis. The scale matters. With tens of thousands of controls, subtle differences become clearer.

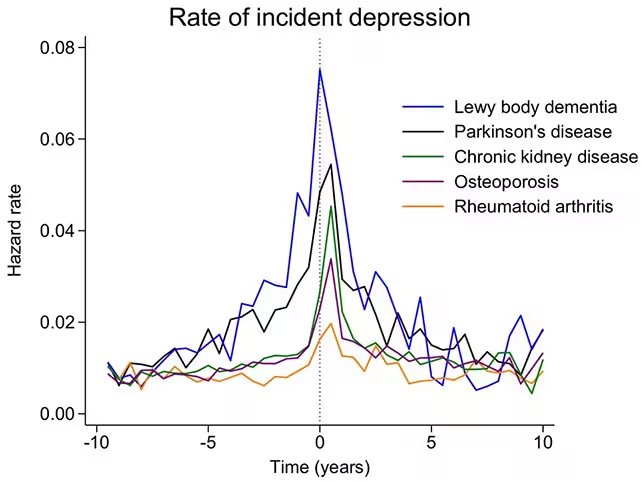

Depression was not just slightly more common in people who went on to develop these neurological disorders. It rose significantly. Rates of recorded depressive symptoms began to climb around eight years before a formal neurological diagnosis. And the elevated rate did not disappear after diagnosis—it remained higher for at least five years afterward.

Among the two brain disorders studied, the association was strongest for Lewy body dementia. The authors suggest this may reflect the disease’s impact on the brain systems that regulate mood and the fact that Lewy body dementia typically progresses more aggressively than Parkinson’s disease.

Interpreting the link

What could explain depression appearing so early? The simplest explanation is that depression, in many cases, marks early biological changes in the brain—chemical imbalances, loss of neurons that produce neurotransmitters such as dopamine, or the spread of protein aggregates known as Lewy bodies that disrupt circuits for mood and cognition. In other words, depressive symptoms might be one of the first visible signs of neuron-level disease processes taking hold.

But caution is required. This is an observational study. Correlation is not causation. Other factors that accompany neurodegeneration—persistent sleep disturbances, evolving cognitive decline, inflammation, medication side effects—might drive mood symptoms independently of the core disease process. The researchers acknowledge this and underline that their use of chronic-illness comparison groups was designed to reduce the chance that depression simply reflects the burden of living with a long-term medical condition.

The median age at diagnosis for Parkinson’s disease or Lewy body dementia in this cohort was 75 years. That detail matters for clinicians: when someone receives a first-ever diagnosis of depression late in life, it may be prudent to consider early-stage neurodegenerative disease in the differential diagnosis and to follow up with cognitive screening, sleep assessments, or referral to neurology as appropriate.

Clinical and research implications

There is a practical side to these findings. If depressive symptoms can flag evolving Parkinsonian disorders years ahead of motor decline, opportunities open up. Patients could be offered earlier support for mood, cognitive rehabilitation, or lifestyle measures that maintain function. For researchers, earlier identification widens the window to study disease mechanisms and to test potential disease-modifying therapies at stages when interventions might be more effective.

The authors argue for systematic mental-health screening in patients diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease and Lewy body dementia. They write that sustained vigilance for depression may help clinicians initiate antidepressant therapy or other interventions sooner, potentially slowing complications linked to mood and cognitive deterioration.

Still, unanswered questions remain. Which biomarkers or imaging signals best predict which patients with late-life depression will go on to develop neurodegeneration? Could targeted treatment of depression alter the trajectory of these brain diseases? And how much of the observed association is mediated by sleep disorders such as REM sleep behavior disorder, known to precede Parkinsonian syndromes in some people?

Expert Insight

"The study reinforces what clinicians have long suspected: mood changes can be an early chapter in a neurodegenerative story," says Dr. Emily Carter, a neurologist who specializes in movement disorders. "Recognizing depression as more than a psychiatric diagnosis in older adults—viewing it sometimes as a neurological red flag—changes management. It prompts cognitive screening, careful medication review, and discussion of prognosis and support needs with patients and families."

Dr. Carter adds that research should now focus on integrating mood assessments with biomarkers—imaging, cerebrospinal fluid assays, and wearable monitoring—to build predictive models that are clinically useful.

For patients and clinicians alike, the take-home is pragmatic rather than fatalistic. Late-onset depression should not be dismissed as an isolated psychiatric event. It may be the earliest audible clue that something is changing in the brain. Acting on that clue—through screening, multidisciplinary care, and targeted research—gives people more time to access therapies, services, and clinical trials when they can still make a difference.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

bioNix

Whoa... that stuck with me. Depression years before movement issues? kinda scary but maybe gives a chance to act earlier. More screening pls clinicians need to watch

Leave a Comment