6 Minutes

Darkness can be loud. In a crowded galaxy cluster, a faint whisper of light—no brighter than a handful of stars clustered together—may have revealed one of the most compelling candidates for a dark galaxy yet discovered.

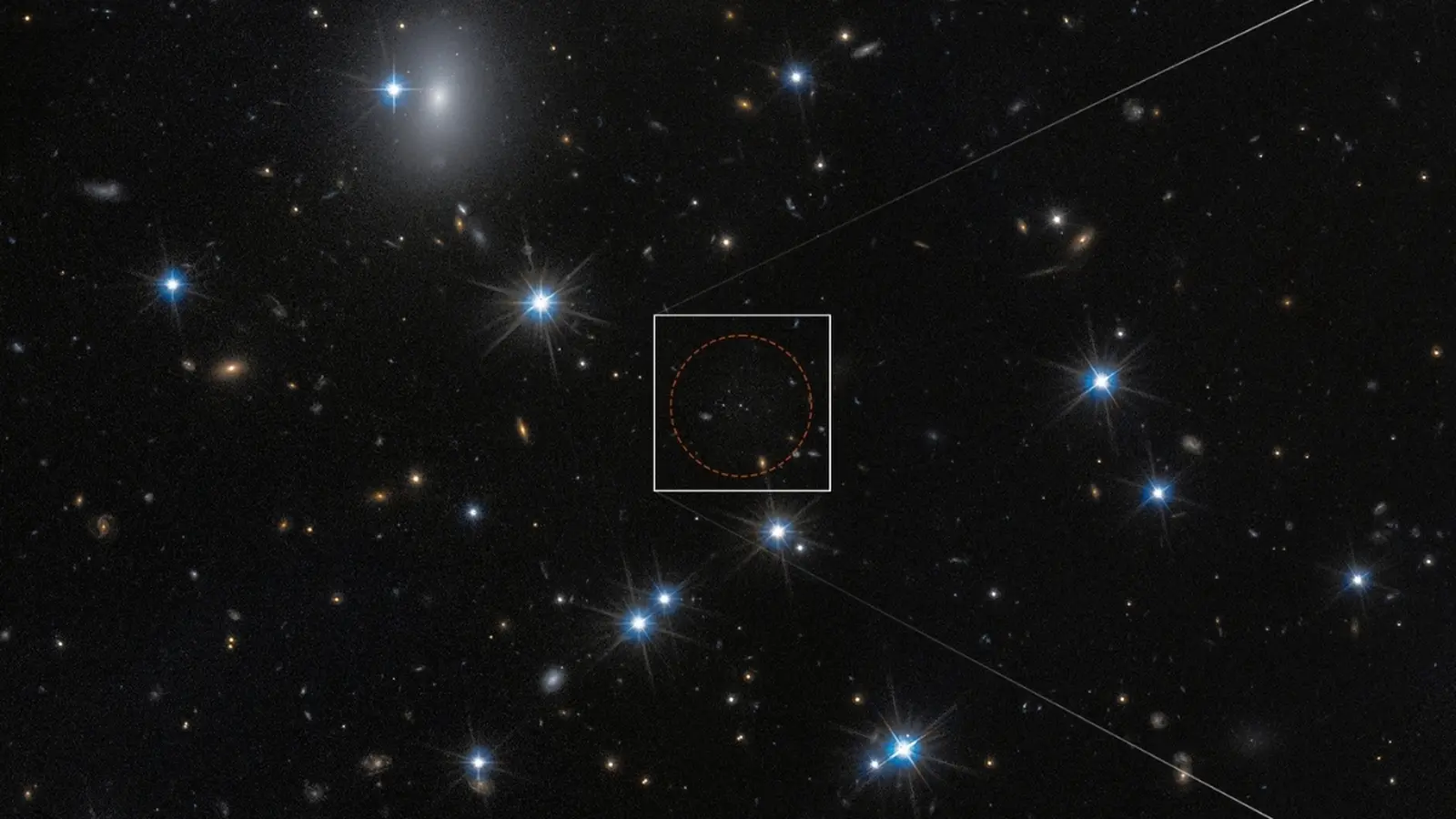

Most people picture galaxies as glittering islands of stars. Yet some systems hide their stellar content so well that they appear nearly invisible against the cosmic background. These dark or ultra–low-surface-brightness galaxies challenge our detection methods and our ideas about how galaxies form and survive. CDG-2, spotted in the Perseus cluster roughly 300 million light-years away, stands out because it was found not by its diffuse starlight but by the compact star clusters that orbit it—globular clusters (GCs).

Finding a galaxy by its globular clusters

Globular clusters are tight, spherical collections of stars bound by gravity, sometimes containing millions of stars. They often sit in the halos of galaxies, relics of earlier formation epochs. The new study, led by Dayi (David) Li, a postdoctoral fellow in statistics and astrophysics at the University of Toronto, looked for unusually tight groupings of GCs in deep survey data. The team combined observations from the Hubble Space Telescope, the European Space Agency's Euclid mission, and Japan's Subaru telescope to hunt for these telltale assemblies.

The low-surface-brightness galaxy CDG-2, within the dashed red circle at right, is dominated by dark matter and contains only a sparse scattering of stars. The full image from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope is at left. (NASA, ESA, D. Li (Utoronto), Image Processing: J. DePasquale (STScI))

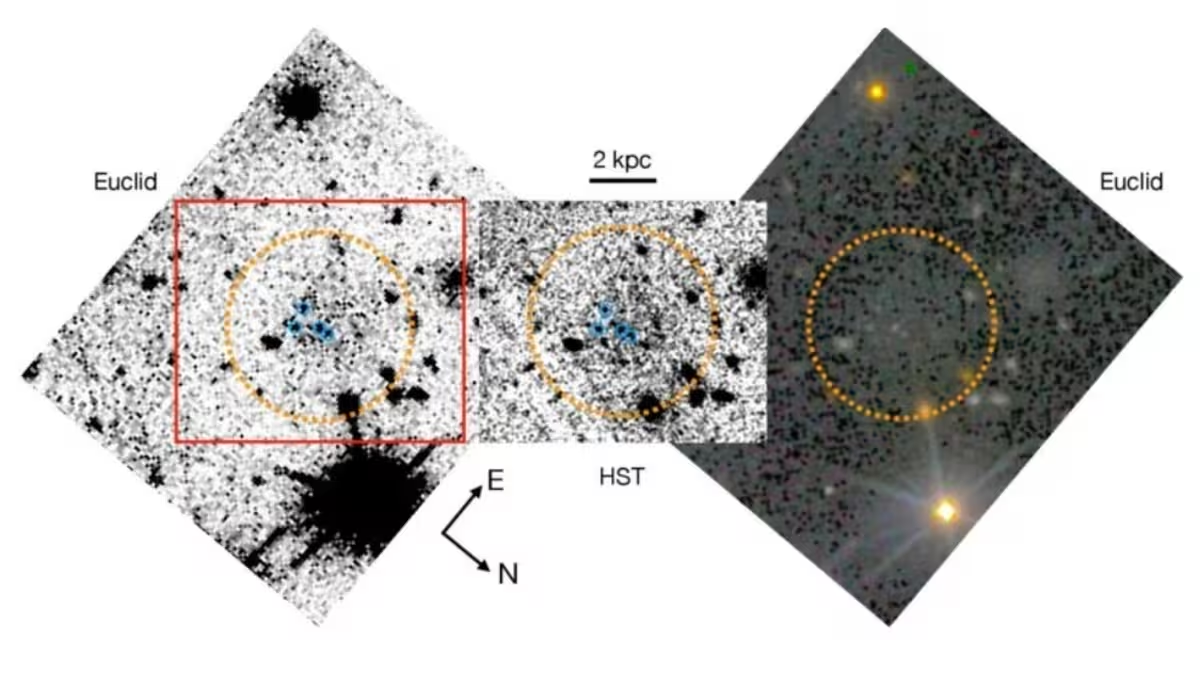

Hubble resolved four closely associated globular clusters in the Perseus cluster. That alone would be intriguing but not conclusive. The team then applied robust statistical techniques and image-stacking methods across the three datasets. When the Hubble ACS frames were stacked and compared with Euclid's VIS images, a faint, diffuse glow appeared around the quartet of clusters. That halo of unresolved starlight is the smoking gun: it suggests a faint galaxy beneath the clusters, whose individual stars are too dim to pick out one by one.

"This is the first galaxy detected solely through its globular cluster population," Li said in a press statement. Under conservative assumptions, the authors estimate that the four globular clusters represent the entire GC population of CDG-2. If true, those clusters account for about 16% of the galaxy's visible light, and the system's total luminosity is roughly equivalent to six million Suns—extremely faint for a galaxy that nevertheless appears to be dark-matter dominated.

These images are cutouts from Euclid's VIS and the Hubble's Advanced Camera for Surveys. The central section stacks Hubble's ACS images and shows extremely diffuse emissions around CDG-2s' four GCs. Euclid data confirms it. (Li et al., ApJL, 2026)

Why does this matter? For one thing, detecting a galaxy through its globular clusters opens a new observational pathway. Globular clusters are compact and bright enough to be picked out in deep surveys even when the host galaxy is nearly invisible. That makes them effective signposts for dark or quenched galaxies in dense environments such as Perseus. It also forces us to rethink thresholds: a system can have very little diffuse starlight yet still be a coherent galaxy with its own dark matter halo and a surviving GC population.

Physical implications and origin scenarios

One plausible explanation for CDG-2's faintness is environmental stripping. In clusters, ram pressure and tidal interactions can remove gas from small galaxies or halt star formation by heating or sweeping away the cold gas that would otherwise form new stars. Globular clusters, being tightly bound and dense, are more resistant to tidal disruption; they can survive the harsh cluster environment while the more diffuse stellar component fades or is lost. The result: a dark-matter-dominated halo decorated with a handful of surviving GCs.

The researchers compare CDG-2 immediately to a previously reported object, CDG-1. CDG-2's detectable diffuse emission raises the question: could CDG-1 be an even more extreme case—an almost pure dark-matter halo with only GCs left as the visible tracers? The authors argue that high-quality follow-up observations of CDG-1 could reveal whether it, too, hosts faint starlight beneath its clusters or whether it truly lacks any diffuse stellar component beyond its GCs.

Expert Insight

"Finding a galaxy by its globular clusters is like tracking a hidden city by its streetlights," says Dr. Maya Chen, an observational astrophysicist who studies low-surface-brightness systems. "The clusters are concentrated, bright beacons. If those beacons cluster together in a way that statistics tell us is unlikely to be random, we must take seriously the idea that a faint galaxy lies beneath. CDG-2 gives us a new handle on the faintest bound systems and the role of environment in shaping them."

This discovery also underscores the synergy between missions. Hubble's high-resolution imaging, Euclid's wide-field, deep optical mapping, and Subaru's ground-based depth provide complementary perspectives. Combining them with careful statistical modeling turned what might have been a curiosity into a strong candidate for a dark galaxy.

Beyond cataloging another oddball in the zoo of galaxy types, CDG-2 forces larger questions: how common are such nearly starless halos, and what do they tell us about the low-mass end of galaxy formation and the behavior of dark matter on small scales? Observational campaigns targeting GC-rich clumps in other clusters will test whether CDG-2 is rare or representative. Either outcome will sharpen our picture of how galaxies survive—or disappear—under the cluster's influence.

Whether CDG-2 turns out to be an outlier or the first of many will depend on follow-up imaging and spectroscopy. For now, the galaxy hides in the thin glow around a few bright clusters, reminding us that sometimes the universe speaks softly—and it pays to listen closely.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

astroset

Wow, cosmic hide and seek! A galaxy found by its globular clusters not stars... kinda poetic, exciting and spooky. If CDG-1 is even darker, mind blown. Need spectra tho!

Leave a Comment