9 Minutes

On November 27, a dramatic accident at Russia's Baikonur Cosmodrome disrupted the country's ability to send crews and cargo to the International Space Station (ISS). Although the Soyuz MS-28 mission reached orbit and the three-person crew arrived safely, imagery and inspection reports show a serious collapse of a key maintenance cabin at Site 31/6 — a failure that has put Russia's Soyuz and Progress launches on pause.

What happened at Baikonur — and why it matters

The Soyuz MS-28 launch lifted off normally at 09:27:57 UTC. Minutes later, drone footage revealed the 8U216 mobile maintenance cabin upside down in the flame trench beneath the pad. The crew — cosmonauts Sergey Kud-Sverchkov and Sergei Mikayev plus NASA astronaut Christopher Williams — docked safely with the ISS, but the damage to the ground infrastructure immediately rendered Site 31 unable to host further Soyuz or Progress launches.

Drone footage of Site 31/6 before (above) and after (below) launch, showing the damage to the maintenance cabin.

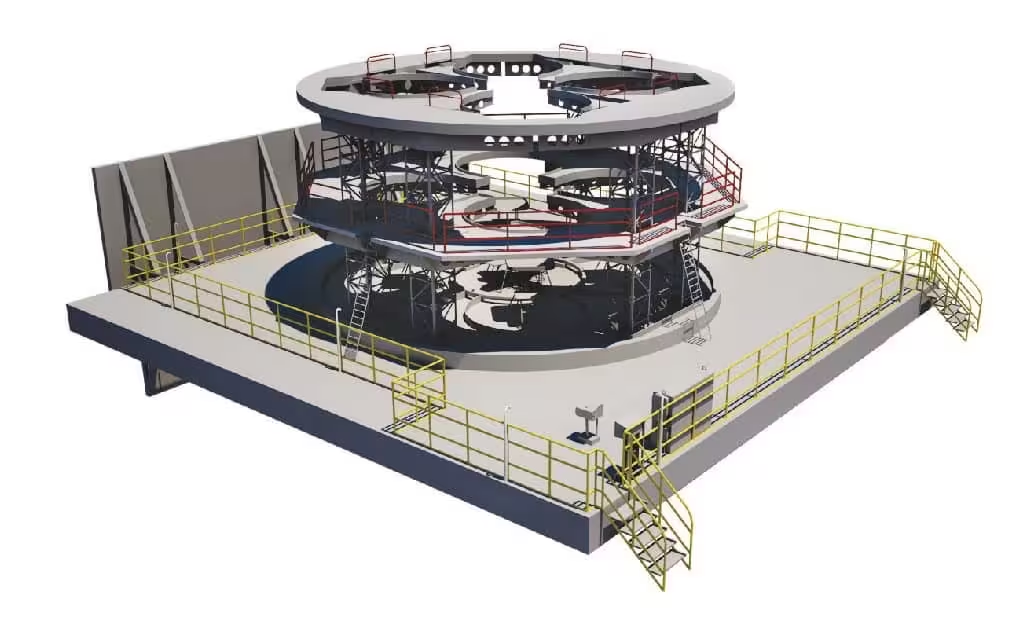

The 8U216 is not a decorative fixture. This 130-plus metric-ton mobile metal platform is extended beneath the launch table during preparations to allow engineers access to the rocket’s engines, install pyrotechnic matches, remove protective covers, and perform final checks. It sits in a recess, or nook, beside the flame trench and is locked in place during liftoff. According to preliminary reports and Roscosmos statements, pressure differentials generated during ignition and ascent may have pulled the cabin from its sockets and hurled it into the trench roughly 20 meters below.

Roscosmos confirmed the event while stressing the mission’s success and the health of the crew. The agency reported that launch-pad inspections are routine and stated that spare components exist to repair the damaged systems. But inspection teams also flagged the possibility that the locks that hold the cabin in place either failed or were not fully engaged before launch, and some experts argue the cabin itself may be too damaged to repair.

Technical context: the 8U216 cabin, Soyuz complexes and limits of alternate sites

The mobile service cabin at Site 31/6 is part of infrastructure built around the R-7 family of launch vehicles — the same basic rocket architecture that has served Soyuz missions since the 1960s. Sites across Baikonur and other Russian complexes use similar equipment; the 8U216-type cabins were originally manufactured in that era and variants continue to be produced for refurbishments.

The immediate problem for Roscosmos is that not all launch complexes can support crewed flights to the ISS. While Russia operates other cosmodromes — Plesetsk in the north, Vostochny in the Far East, plus other pads at Baikonur such as Gagarin's Start — logistics, orbital geometry and pad configurations limit which pads can routinely launch Soyuz or Progress missions to a low-Earth orbit rendezvous. In short: Baikonur’s Site 31/6 is currently the only fully certified site for routine crewed and Progress cargo launches to the ISS.

The agency has a few options, each with trade-offs. Teams could attempt to cannibalize an 8U216 from another site (for example, Site 43 at Plesetsk) and re-establish service at 31/6, or manufacture a replacement cabin domestically. Either path requires careful inspections of other pad components — the flame trench, supporting structures, locks and electrical systems — because secondary damage could extend repair timelines. Preliminary estimates for restoring Site 31 range widely, from a few months to as long as three years, driven by whether the cabin must be rebuilt and how many ancillary parts need replacing.

The inspections must also conclude with at least one uncrewed test launch before resuming crewed flights, a standard safety step that adds time but is necessary to reassure both engineers and international partners.

Operational impacts and mission delays

With Site 31 offline, Russia cannot currently launch Soyuz crew rotations or Progress resupply missions from Baikonur. The immediate casualties on the schedule include the Progress MS-33 cargo mission, which had been set for December 21, 2025, and crewed mission Soyuz MS-29, planned for July 14, 2026. Roscosmos has suggested it may try to rework logistics to launch some cargo flights from Vostochny, but making that move requires significant pad modifications, trajectory planning and safety certification.

Complicating matters, Roscosmos no longer operates from the Guiana Space Centre in French Guiana, having withdrawn personnel earlier. That removes another potential alternative for shifting launches away from Baikonur quickly.

Beyond immediate schedule slips, the accident arrives against a backdrop of geopolitical and commercial strain. Since 2022, international sanctions and deteriorating partnerships have already constrained Roscosmos: collaborative missions such as ExoMars were disrupted, planned joint science and instrument developments have been curtailed, and European Space Agency payloads that had been slated for Soyuz launches were reassigned to other providers. A prolonged outage at Baikonur risks further disruption to contractual commitments and to the cadence of ISS operations.

The maintenance cabin at Site 31/6

Historical perspective and safety concerns

Baikonur has a long history — including some dark chapters. The Nedelin catastrophe of 1960, during an R-16 missile test, remains the most lethal accident in the history of spaceflight, with dozens of casualties. Today’s safety culture is very different, but the incident at Site 31 reminds engineers and managers how vulnerable complex launch infrastructure can be to mechanical failures, human error, and unforeseen aerodynamic or pressure effects at ignition.

Roscosmos’ statement framed the event within normal post-launch inspection procedures while promising repairs and the availability of spare parts. Still, independent industry sources quoted by specialist outlets indicate repair work may be extensive. The agency’s capacity to source replacement hardware domestically — or to transfer an intact cabin from Plesetsk — will determine the pace of recovery.

What it means for the ISS and international partners

The ISS is a multinational facility with overlapping access strategies: astronauts and cosmonauts reach it via multiple vehicles, and cargo can be delivered by Progress, Northrop Grumman Cygnus, SpaceX Dragon, and others. Currently, partner agencies and mission planners can mitigate some operational risk by reallocating cargo deliveries and crew rotations among available vehicles. But a long-term inability of Roscosmos to provide Soyuz or Progress services could force more permanent schedule changes, budget reallocations, and new commercial agreements for launch services.

For crew safety and station logistics, redundancy is crucial. The temporary loss of one partner’s launch capability is manageable if announced early and if alternatives remain available. The speed and transparency of Roscosmos’ inspection and repair program will therefore shape confidence levels in both its domestic and international stakeholders.

Expert Insight

Dr. Elena Morozova, an aerospace systems engineer formerly with a Russian launch-site integration team, offered a measured appraisal: "The 8U216 is an old but critical piece of ground hardware. Its failure doesn’t imply the Soyuz vehicle is unsafe, but it highlights how ground systems age and how single-point infrastructure can create operational single points of failure. Rapid, methodical inspections and at least one uncrewed proof launch are essential before crews return to that pad."

"If spare modules are available nearby, repairs can be relatively quick. If the cabin must be rebuilt and major structures repaired, the timeline stretches. Either way, this is a wake-up call for continued investment in pad modernization and international contingency planning," she added.

Looking ahead: repairs, tests and the longer view

Roscosmos says spare parts are available and that the damaged systems will be repaired. Whether teams transfer a cabin from Plesetsk, manufacture a new unit, or pursue a mix of both will be decided after thorough inspections. Engineers must also confirm that locks, structural mounts, and nearby equipment suffered no latent damage that could cause future failures.

Operationally, the most prudent path involves transparent timelines, realistic uncrewed testing, and coordinated scheduling with ISS partners. For now, the incident is a reminder that spaceflight depends not only on rockets but on the ground infrastructure that supports them. Even a successful launch and a safe crew arrival cannot erase the ripple effects of a pad failure — from postponed cargo flights to the political and commercial headaches that follow.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

skyforge

Makes sense that ground systems age, one failed part can mess schedules for yrs. Transparent testing and an uncrewed flight before crews return, imo.

labquark

Is this even true? The cabin flipped into the trench, seems like lock failure or bad procedure. Waiting on CCTV proof... hmmm

fluxnode

Wow, that footage is wild. Lucky the crew made it, but damn, this looks like a close call for ground crews too. Who inspects those locks??

Leave a Comment