5 Minutes

Modern low-Earth orbit (LEO) has become a crowded, fast-moving environment. New research warns that a single powerful solar storm could cascade through satellite mega-constellations and trigger collisions that make orbital access dangerously difficult for years. The paper, now available as a preprint on arXiv, frames the current constellation architecture as a fragile "house of cards"—beautifully engineered until the rare event that topples it.

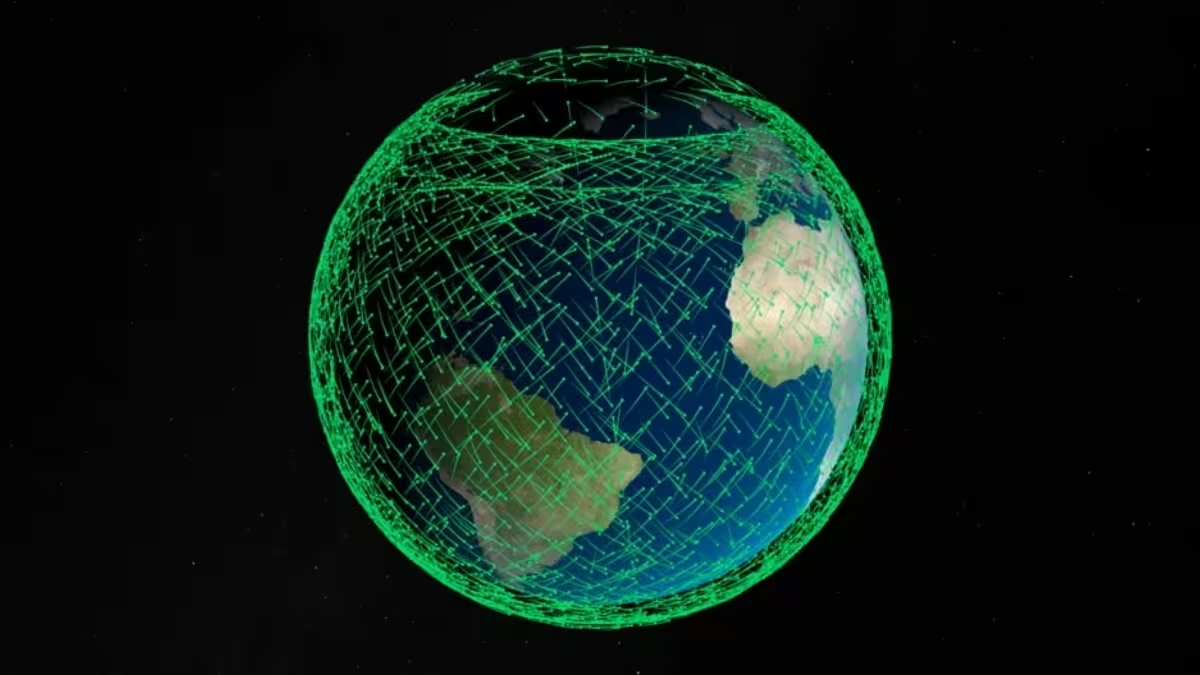

Paths of Starlink satellites as of February 2024

Why one storm matters: atmospheric chaos and broken radios

Solar storms influence satellites in two critical ways. First, injected energy from the Sun heats Earth’s upper atmosphere, lifting and expanding it. That atmospheric bulge increases drag on satellites in LEO, altering their velocity and orbital position unpredictably. Operators must burn propellant to maintain altitude or execute avoidance burns when two objects threaten a close approach.

Second—and potentially more dangerous—charged particles and electromagnetic disturbances can degrade or disable a satellite’s navigation and communications systems. If a satellite loses the ability to receive ground commands or to determine its own position precisely, it cannot execute collision-avoidance maneuvers. Combine increased drag with unresponsive spacecraft, and you have an immediate recipe for collisions.

A ticking clock for collisions: from minutes to days

The authors, including Sarah Thiele (formerly a PhD student at the University of British Columbia, now at Princeton), quantify how precarious the situation has become. Across all LEO mega-constellations, a close approach—defined as two satellites coming within one kilometer—occurs roughly every 22 seconds. For the Starlink network specifically, a near miss happens about every 11 minutes. To reduce risk, each Starlink satellite performs on average 41 avoidance maneuvers per year.

Those routine maneuvers may be manageable until an edge-case event arrives. To capture the immediacy of that risk, the researchers introduce a new metric: the Collision Realization and Significant Harm (CRASH) Clock. Using constellation densities and current collision-avoidance procedures, their calculations show that if ground operators instantly lost the ability to send avoidance commands, a catastrophic collision would likely occur in about 2.8 days (as of June 2025). By contrast, in 2018—before the megaconstellation era—that window was about 121 days.

Even a single day without control is hazardous: the paper estimates roughly a 30 percent chance that a 24-hour outage would trigger a collision large enough to seed the long-term cascade known as Kessler syndrome—the self-sustaining generation of debris that can render space effectively unusable.

Historical precedent and worst-case scenarios

Solar storms with severe effects are not only theoretical. The May 2024 "Gannon Storm" forced more than half of all LEO satellites to expend propellant for repositioning maneuvers. And the Carrington Event of 1859 remains the strongest solar storm on record; if an event of that magnitude struck Earth today, it could disable satellite command and control for far longer than a few days, with far higher consequences.

Where Kessler syndrome is often discussed as a decades-long degradation, the CRASH Clock highlights a more immediate collapse scenario: a rapid cascade initiated by loss of command and the sudden change in orbital dynamics during a strong geomagnetic disturbance.

What can be done? Technology and policy levers

There are no simple fixes, but several practical mitigations can reduce risk. Improvements include:

- Hardened communications and radiation-tolerant electronics so satellites remain controllable during solar storms.

- Autonomous on-board collision avoidance: spacecraft that can sense and react to threats independent of ground commands.

- Stronger space traffic management and shared real-time data on spacecraft positions to coordinate evasive actions across operators.

- Design rules that reduce debris generation and improve de-orbiting capability at end-of-life.

These technical options must be paired with regulation, international coordination, and investment in monitoring infrastructure. Solar weather gives little advance notice—often a day or two at most—so preparedness and resilience are essential.

Broader implications for space access and industry

The trade-offs are stark. Mega-constellations deliver broadband, Earth observation, and scientific benefits at an unprecedented scale. Yet their density amplifies systemic vulnerability: a single large solar storm could strand future missions, complicate human spaceflight, and blunt scientific initiatives that rely on satellite services.

Making informed policy choices requires recognizing both the socioeconomic benefits of LEO services and the catastrophic downside risk of a collapse in orbital safety. The arXiv preprint lays out data-driven urgency—one that operators, policymakers, and the public should take seriously.

Expert Insight

"We are entering an era where human-made systems in orbit are interdependent at an unprecedented scale," says Dr. Elena Morales, an orbital dynamics researcher familiar with constellation operations. "That interdependence means a single natural event—solar weather we can’t prevent—can cascade across networks. Building redundancy into communications and smarter autonomy on each satellite will buy us time; coordinated international rules will buy us the future of access to space."

The research is a call to action: sustain the benefits of LEO infrastructure while urgently strengthening its resilience to rare but catastrophic solar events. Space access is a shared global asset; protecting it requires engineering, policy, and foresight working together.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

coinpilot

Is this even true? seems a bit dramatic, but the numbers? How often do constellations really go dark, for real. curious

astroset

wow, that CRASH Clock is terrifying. if control goes down for days we could lose access to whole swaths of LEO, yikes... who's ready for that?

Leave a Comment