10 Minutes

Why ISA feels more like a nag than a safety system

Intelligent Speed Assistance (ISA) was introduced as a technology to help drivers respect speed limits and reduce collisions. In principle, the idea is simple and attractive: a camera, map data and some logic help your car notice the local limit and nudge you back into compliance. In practice, the rollout and mandatory adoption of ISA across European markets has revealed important limitations — human, technical and regulatory — that turn the feature from a potential safety aid into a recurring source of distraction and driver distrust.

For many motorists the experience is familiar: you perform a precise, context-sensitive maneuver — say, overtaking a slow-moving tractor on a narrow country road — and mid-maneuver the vehicle chirps, flashes, or emits a harsh warning because it believes you briefly exceeded a posted limit. The noise jolts your focus at the moment you need calm, steady judgment. Repeated occurrences train drivers to ignore the alerts, and that degraded trust is the opposite of what any effective safety system should produce.

From helpful assistant to background noise

There are two things a successful driver assistance technology must have: technical accuracy and human trust. ISA is struggling on both fronts. Its sensors and algorithms are fallible — they misread signs obscured by dirt, foliage, snow or stickers, and they sometimes pick up speed markings meant for adjacent lanes, exit ramps, or temporary works zones. Even high-definition map data can’t keep pace with the messy, evolving reality of roadworks, ad hoc signage or vehicles that display numbers on their rear doors.

When a system warns too often or is frequently wrong, drivers do what humans have always done with annoying alarms: they tune them out. That Pavlovian desensitization is the real hazard. A warning system that cries wolf every few minutes undermines the driver’s incentive to take real alerts seriously — and in the event of a genuine emergency, that complacency can be lethal.

Key real-world failure modes

- Misread signs: a faded or partially covered sign produces an ambiguous camera read.

- Wrong target: signs for a different lane, service road or temporary restriction apply to other users but are read as relevant.

- Outdated map data: speed limits change; maps do not always update fast enough.

- False positives during context-dependent maneuvers: overtaking, merging, or pulling out to pass agricultural equipment.

How the human factor becomes the weak link

Human factors specialists stress that the best automation complements human judgement rather than replaces it. ISA too often behaves like the opposite: an insistently punitive layer that treats drivers as if they cannot be trusted to apply context. Modern drivers are required to manage multiple tasks, and any additional intrusive alert increases cognitive load. When drivers must continuously reconcile their own perception of a safe speed with the car's blaring objection, attention is diverted from the outside environment to the dashboard.

There are psychological dynamics at play. Early exposure to a reliable system breeds trust; frequent false alarms breed resignation. Users move through a familiar arc: curiosity, cooperation, frustration, and finally indifference. Once alerts become disregarded, the system has failed as a safety measure. Worse, this distrust spreads: skeptical drivers may disable other driver assistance systems or refuse to adopt future innovations.

Technical realities: why ISA trips up

At the technical layer, ISA relies on two primary inputs: real-time sign recognition (camera-based) and digital speed limit databases. Each is useful but imperfect.

- Camera-based sign recognition depends on visibility and clean lines of sight. Everything from dirt splatters to a low sun can compromise detection.

- Map-based speed data can be out of date or mismatched with local signage, especially where temporary restrictions are common (construction, events, seasonal limits).

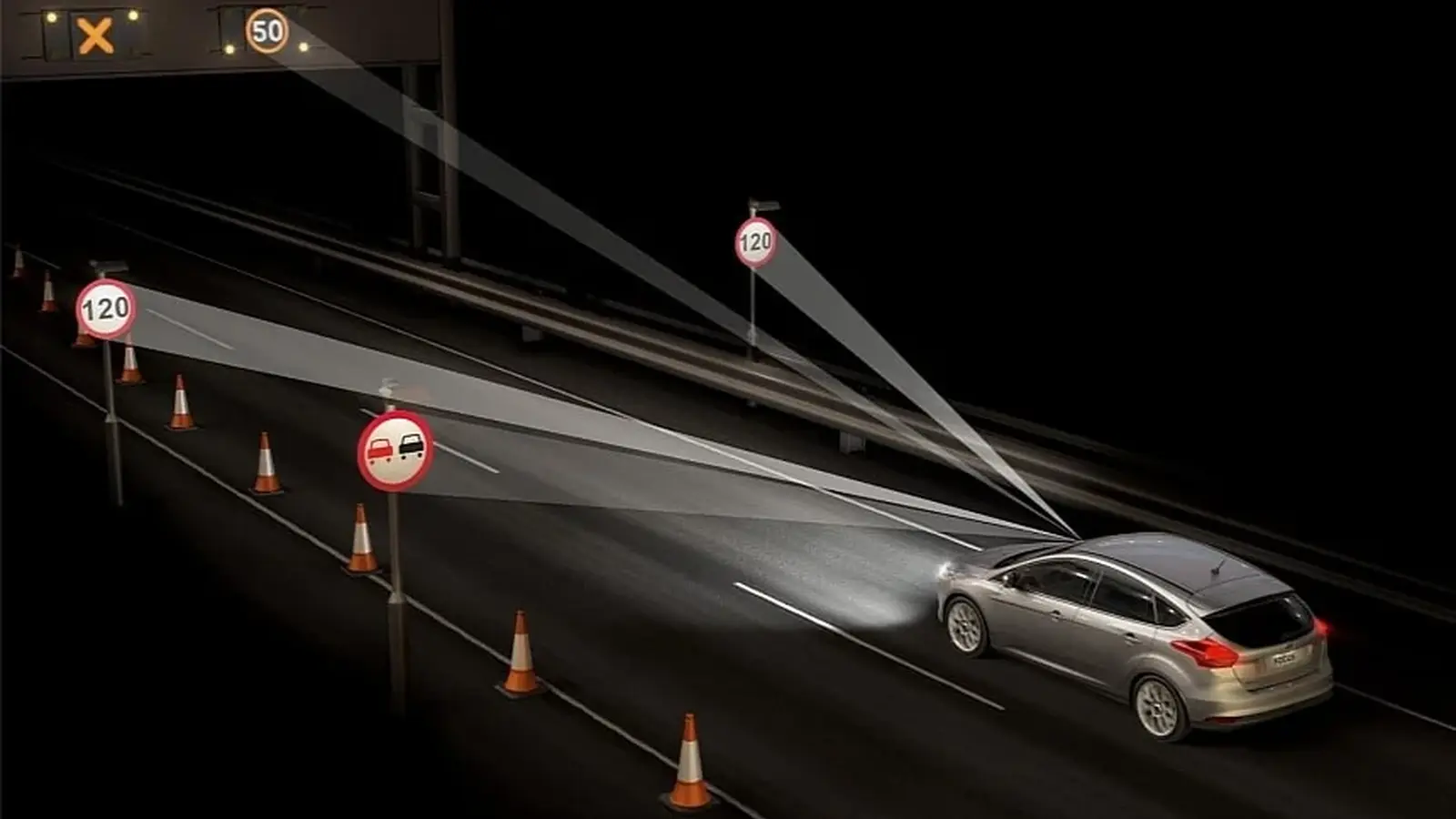

The fusion of the two inputs should, in theory, produce robust outputs. In reality the systems often lack the nuance to weigh conflicting signals correctly or to understand driver intent. For example, briefly accelerating to overtake a slower vehicle requires judgment about road width, sightlines and oncoming traffic — parameters ISA typically cannot assess, so it reacts to a single numeric readout rather than the full driving context.

Examples from everyday driving

Imagine a lane-dividing sign on a dual carriageway that marks a slip road with a 50 kph advisory. Your car’s camera reads the “50” while you continue on the 100 kph mainline. The system flags a violation. Or picture a service-vehicle parked at the roadside with a temporary 30 kph in a work bubble; your line of sight momentarily catches the ‘30’ as you pass at 50, and the car obligingly scolds you.

These are not hypothetical edge-cases; they are routine events in many driving environments. The result is a steady stream of corrective chimes and visual alerts that are disproportionate, ill-timed and often incorrect.

Consequences on driver behavior

- Reduced situational awareness: drivers look down at the cluster to confirm the system rather than at the road.

- Reactive driving: an emphasis on satisfying the car’s constraints instead of interpreting the road conditions.

- Loss of speed sense: drivers can stop using their own experience to judge appropriate speed because they expect the car to police them.

When regulation outpaces reality

Regulators are motivated by commendable ambitions: fewer fatalities, lower-speed impact scenarios and a cultural shift toward safer driving. Mandating ISA in new vehicles is a regulatory instrument intended to accelerate those outcomes. But one-size-fits-all mandates can produce one-size-fits-nobody technology when the rules do not account for the messy diversity of roads and driver tasks.

Designing a requirement is different from creating a robust implementation. Standards define minimum performance — often under controlled test conditions — and manufacturers implement to meet those benchmarks. The result can be a checkbox technology that is legally compliant but operationally clumsy. A car that meets the letter of the law for sign recognition and map checking may still create dangerous secondary effects in the cabin because it cannot interpret context.

Comparisons: ISA vs other ADAS features

Automotive safety has seen transformative innovations: electronic stability control, ABS, airbags and advanced emergency braking systems (AEB) each delivered measurable reductions in harm because they assist in situations where human reaction is limited or where the physics of a crash are clear-cut. Those systems typically operate in moments of acute danger where intervention is obviously beneficial.

ISA differs because it intervenes in an anticipatory, continuous way. Where AEB steps in to prevent a collision, ISA steps on the mental toes of the driver repeatedly during everyday behavior. That distinction matters: drivers accept occasional intervention during a clear emergency but resent, and ultimately ignore, repetitive corrective nudges that seem arbitrary.

Market and manufacturer responses

Major manufacturers have implemented ISA in various ways. Some OEMs allow configurable sensitivity or temporary suspension; others make the alerts more or less intrusive. Market feedback has influenced user-interface choices — but not always speedily enough. Dealers and service departments are starting to receive consistent reports of customers disabling or downgrading ISA-related features.

The commercial risk is twofold: dissatisfied drivers and diminished uptake of other safety features. Automotive brands value seamless, trust-building experiences. A buzzy, mistrusted ISA undermines that goal and could harm brand loyalty if customers associate the vehicle with incessant nagging.

Designing a better ISA: technologies and principles that would help

ISA doesn’t have to be a blunt instrument. Several improvements could make it far more useful and less intrusive:

- Context awareness: fuse camera data with radar, lidar and vehicle telemetry to understand whether a brief speed increase is a safe, deliberate maneuver (e.g., overtaking) or risky acceleration.

- Time-aware rules: correlate signs with timestamps and event data to avoid reacting to old or irrelevant temporary signage.

- Tiered alerts: use gentle haptic or visual nudges at low exceedances and reserve audible, high-priority alarms for sustained or dangerous speed violations.

- User-configurable profiles: let drivers set a tolerance band (within legal policy) for advisory alerts while maintaining enforceable limits for legal or commercial contexts.

- Better map hygiene: accelerate map refresh cycles and crowdsource corrections from fleets and connected vehicles.

These changes require investment and regulatory willingness to accept complexity instead of a single fixed standard. The technology exists; integrating it properly and testing in real-world conditions is the challenge.

What good ISA looks like

- Soft guidance in daily driving: unobtrusive indicators that help recalibrate speed sense.

- Active collaboration during maneuvers: minimal interference when steering or lane positioning signals a justified speed change.

- Trust-preserving alerts: only alarm when there’s a real safety benefit, not for every minor and harmless deviation.

Policy trade-offs and regulatory suggestions

Regulators should be striving to achieve outcomes — fewer crashes, fewer severe injuries — not merely narrower compliance metrics. Policies that mandate ISA should incorporate performance-based measures and real-world testing protocols that take human factors into account.

A few concrete policy ideas:

- Require manufacturers to demonstrate low false-positive rates in diverse, real-world conditions as part of type-approval tests.

- Mandate a human-factors evaluation focused on distraction and habituation risk before approving the feature.

- Encourage adaptive frameworks that allow manufacturers to implement context-aware solutions rather than only prescriptive checklists.

Lessons from other tech-infused transitions

History shows that mandating technology without establishing user trust can backfire. Consider early lane-keeping or collision alerts that were overly cautious: drivers turned them off. For any assistance feature to create long-term safety gains it must be reliable, explainable and unobtrusive.

Trust is earned through consistent, beneficial performance. Seatbelts, airbags and ABS succeeded because they worked without requiring micromanagement from the driver. ISA can reach that level, but only if it stops behaving like a classroom monitor and starts acting like a competent partner.

Quick recommendations for drivers, manufacturers and regulators

For drivers:

- Familiarize yourself with how your vehicle’s ISA behaves in different environments.

- Use configurable settings wisely and report systematic problems to manufacturers.

- Keep a healthy skepticism: check your speed for safety, not just to appease an alarm.

For manufacturers:

- Invest in sensor fusion and context-aware logic.

- Prioritize human-centered design; reduce auditory intrusions.

- Publish real-world performance data and allow meaningful user feedback.

For regulators:

- Shift from prescriptive checks to performance-based approvals.

- Include human factors and real-world trials in type approval.

- Allow flexibility for smarter implementations that balance enforcement with context.

Conclusion: repair the bridge between driver and machine

Intelligent Speed Assistance is a well-intentioned technology with the potential to save lives. But intention is not enough. In its current, widely deployed form, ISA too often punishes ordinary, context-appropriate driving and rewards passive obedience. That combination erodes trust, increases distraction and can ultimately produce the opposite of the desired safety outcomes.

The path forward is clear: make ISA smarter, gentler and more context-sensitive. Test it outside the lab, in the muddled reality of regional roads, construction sites and mixed-traffic urban environments. Give drivers tools to understand and interact with the system rather than order them to obey. When we design systems that respect human judgment and reduce cognitive load, adoption will follow and safety gains will be real.

Until then, ISA risks becoming an irritant and a liability — the loudest, least trusted new feature in the cockpit. That is a solvable problem, but solving it will require collaboration: engineers, UI designers, regulators and real drivers working together to transform a noisy compliance feature into an intelligent, trustworthy co-pilot.

"A car that shouts at you every time you glance at 51 in a 50 zone isn't enforcing safety — it's eroding the trust that safety depends on."

Source: autoevolution

Comments

citylane

Feels like a classroom teacher nagging you, not a co-pilot. Make it gentler, allow a margin, test on real roads or ppl will just disable it

DaNix

Seen this in fleet cars. Drivers turn it off within weeks, esp in countryside. Needs haptics & context, not alarms

mechbyte

Is this even that hard to fix? cameras, maps, fusion... seems like lazy software or are regs forcing dumb behaviour?

v8rider

Wow this is my nightmare , car nags me mid-overtake, heart racing, then i ignore it next time. Need smarter logic, not constant screaming

Leave a Comment