4 Minutes

End of a high-flying dream?

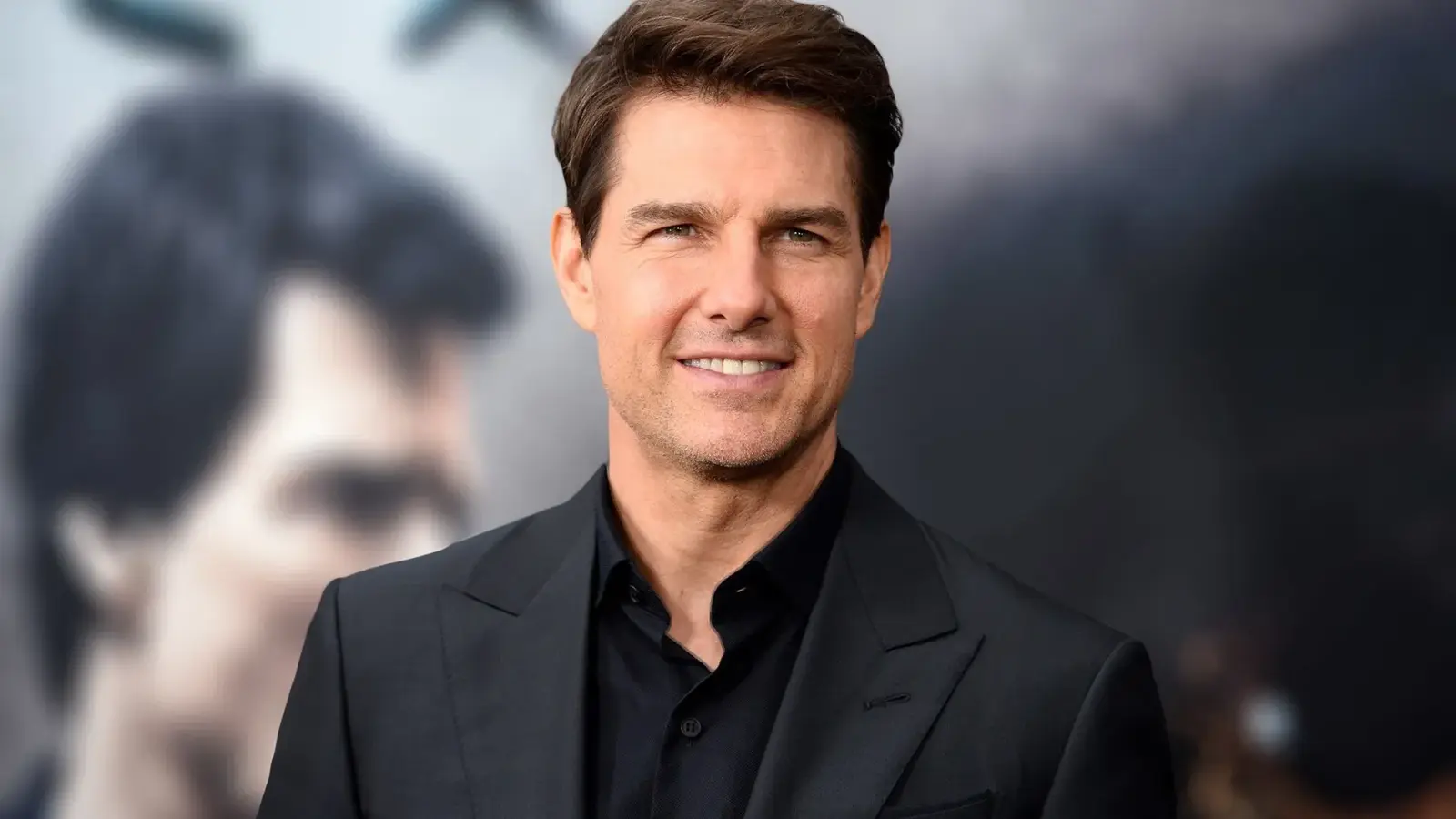

Rumors that a Tom Cruise space movie — a high-profile collaboration with director Doug Liman, SpaceX and NASA — has been cancelled have circulated this week. The project, first hinted at roughly five years ago, promised a $200 million action-adventure partially shot in orbit. It sounded like Hollywood’s boldest stunt yet: an A-list star performing in real microgravity. But according to recent reports, a mix of political hurdles, logistical nightmares, and scheduling conflicts may have grounded the idea before cameras ever left Earth.

What reportedly went wrong

Sources cited by film outlets claim the production needed federal coordination with NASA and special permissions that, in practice, involve the U.S. government. Politics reportedly complicated those conversations — the claim being that clearance would require requests routed through administrations Tom Cruise preferred not to engage with. On the practical side, insurers, mission costs, and medical clearances became sticking points. One report even suggested Doug Liman did not pass the medical tests required for a voyage to space. Add to that the inevitable juggling of Cruise’s and Liman’s busy schedules, and the project faced multiple, overlapping obstacles.

That doesn't mean the idea was without precedent. Filmmakers have long tried to create authentic space cinema: movies like Gravity and The Martian used sophisticated practical effects and VFX, while First Man leaned into physical sets and miniatures to capture the feel of spaceflight. But actually filming in orbit introduces unique layers of complexity — orbital logistics, astronaut training, rocket windows, and catastrophic insurance costs — that no conventional production has faced on a commercial scale.

.avif)

How this compares to other attempts

Doug Liman’s résumé (The Bourne Identity, Edge of Tomorrow) shows a director comfortable with high-concept action rooted in visceral filmmaking. Tom Cruise’s reputation for real stunts (Mission: Impossible franchise set pieces, HALO jump in Fallout) made him a believable candidate to attempt the unprecedented. Still, compared to studio-backed space epics that remain planet-bound for safety and cost reasons, this proposed venture would have been a new species of filmmaking — closer in ambition to space agencies than to soundstage-bound productions.

Industry context and fan reaction

The film community’s response has been mixed: excitement at the possibility of cinema in true microgravity, and skepticism about feasibility. Fans praised the daring concept but many noted that the constraints of insurance and safety should come first. Industry insiders say studios are increasingly interested in spectacle to drive theatrical attendance, but practical limits — especially when human lives and multi-million-dollar rockets are involved — impose hard boundaries.

"Ambition alone can't replace infrastructure," says cinema historian Elena Marquez. "The story of a cancelled space shoot is as much about institutional limits as it is about star power. It reveals how filmmaking now intersects with geopolitics and aerospace policy."

Trivia: NASA has previously allowed film crews limited access to facilities and flown actors on reduced-gravity flights for authenticity, but no mainstream commercial feature has staged scenes aboard an orbital vehicle. Space agencies, companies like SpaceX, and studios are still experimenting with how entertainment and spaceflight might collaborate safely.

Whether the project is dead or merely deferred, the headlines highlight a new chapter in film production — one where government, private space firms, and Hollywood must align. Even if this particular dream is paused, the appetite for real-space filmmaking is unlikely to disappear.

In short: the idea was bold, the obstacles were real, and for now the cameras will keep rolling on Earth.

Leave a Comment