7 Minutes

New fieldwork at Aguada Fénix — the vast early Maya complex in Tabasco, Mexico — shows the site was planned as a cosmogram: a monumental, cross-shaped representation of the cosmos. The discovery rewrites assumptions about how large-scale construction and social organization worked in the Middle Formative period, around 1050–700 BCE.

Rediscovering a hidden giant with LIDAR and fieldwork

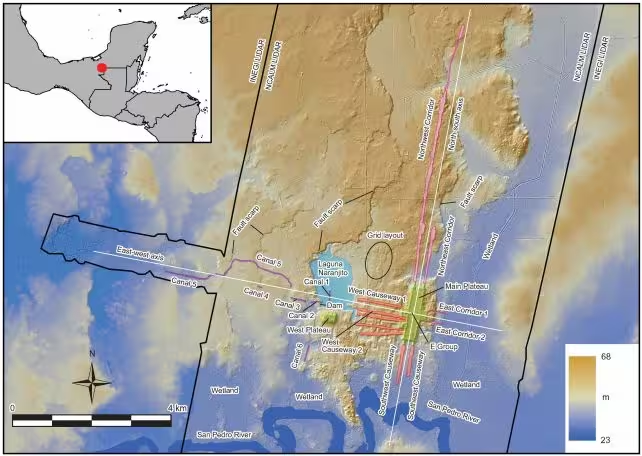

Aguada Fénix first gained widespread attention after airborne LIDAR surveys revealed an unexpectedly large and ordered landscape beneath modern vegetation and settlements in Tabasco, near the Gulf of Mexico. Follow-up LIDAR mapping, targeted excavations and detailed survey work led by Takeshi Inomata (University of Arizona) now show the site is far larger and more deliberately designed than earlier work suggested.

Found at Aguada Fénix, this greenstone object likely depicts a crocodile

The monument’s embedded geometry is striking: a nested, cross-shaped layout with two main axes roughly 9 and 7.5 kilometers long across the broader complex, and a ceremonial hub carved into an artificial plateau. A longest corridor stretching northwest from the center measures approximately 6.3 kilometers and was flanked by raised causeways. These corridors and causeways look less like roads for commerce and more like ritual arteries designed for processions into and out of a central ritual arena.

Cosmogram architecture: mapping the universe in earth and pigment

At the ceremonial heart archaeologists uncovered two nested cross-shaped pits, arranged with deliberate orientation. In the center, a specially curated cache contained pigments placed by direction: blue azurite in the north, green malachite to the east, and yellow ochre with goethite to the south. That ordered placement is the earliest direct evidence of directional color symbolism in Mesoamerica — a motif that later becomes explicit in Classic Maya cosmograms linking colors, directions and elements.

The cache containing the pigment deposits

Alongside pigments were offerings carefully set in the cross-shaped arrangement: seashells suggesting watery associations, and carved jade and greenstone objects depicting crocodiles, birds and even a small ornament interpreted as childbirth imagery. The spatial logic of these deposits — colors, materials and iconography aligned with cardinal directions — points to a worldview materialized in earthworks and ritual practice.

No palaces, no rulers: what egalitarian organization can build

Perhaps the most provocative result from the new investigations is the near-total absence of elite architecture. The site lacks palatial compounds, monumental carved stelae of rulers, or the residential signatures that typically mark a hierarchical center. Instead, the picture is one of large-scale, coordinated communal labor and ceremonial life organized without obvious coercive leadership.

Some of the jade offerings found at the site

Building the main plateau alone required an enormous investment of labor — Inomata and colleagues estimate roughly 10.8 million person-days for earthworks on the Main Plateau and another ~255,000 person-days for associated canals and a dam. Yet, despite sustained use over centuries, parts of the program were left unfinished: canals and waterworks near Laguna Naranjito remain incomplete, hinting at organizational or technical constraints faced by the builders.

Scientific background and methods

LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) has changed archaeology across the Americas by revealing earthworks and settlement patterns under dense vegetation and modern land use. At Aguada Fénix, repeated LIDAR passes provided high-resolution elevation data that allowed archaeologists to map causeways, corridors, plateaus and depressions at landscape scale. Ground-truthing through excavation then linked the features to material culture — pigments, jade, shell — and to radiometric dating, anchoring the construction between about 1050 and 700 BCE.

The layout of Aguada Fénix, with central and western plateaus highlighted in green

Chronology derives from stratigraphic context and radiocarbon dates on charcoal and organic remains associated with construction layers and caches. Combined, those lines of evidence place Aguada Fénix squarely in the Early to Middle Formative period of Mesoamerican prehistory, a time when communities across the region were experimenting with new forms of ritual, settlement and social organization.

Key discoveries and broader implications

- Monumental cosmogram: The nested cross-plan and directional pigment deposits indicate the monument was conceived as a three-dimensional map of the cosmos.

- Egalitarian construction: Large-scale coordination without clear elite architecture suggests collectivized labor and ritual legitimation rather than coercive state control.

- Ritual hydraulics: Canal works near the western axis, left incomplete, emphasize the ritual importance of water but also show technological or organizational limits.

- Cultural continuity: The directional color schema prefigures later Mesoamerican and Maya cosmological systems, linking Aguada Fénix to broader regional symbolic traditions.

The cache offerings include seashells and carved ornaments placed in the cross-shaped pattern, reinforcing the cosmogram interpretation. The shell placements likely signaled water’s ritual role, while jade and greenstone objects connected the monument to luxury exchange networks and cosmological narratives.

Expert Insight

Dr. Elena Morales, archaeologist and specialist in Mesoamerican ritual landscapes, comments: "Aguada Fénix challenges the assumption that monumental scale requires hierarchical power. The site shows how cosmology can mobilize cooperation — pigments, processional corridors and offering caches act as shared language. It’s a reminder that social complexity comes in many organizational forms, not just kings and palaces."

The jade ornament possibly representing childbirth

What this means for archaeology and future research

Aguada Fénix reframes debates about the origins of Maya civilization by showing large, symbolically organized constructions predate the sociopolitical forms once assumed necessary for monumental labor. For archaeologists, the site emphasizes the importance of landscape-scale survey and multidisciplinary integration: remote sensing, careful excavation, pigment analysis and artifact study together reveal how people encoded cosmology into the built environment.

Future work will target unfinished hydraulic features, refine the chronology of construction episodes, and analyze material provenance for jade, shell and pigments to map ancient exchange networks. Researchers also plan comparative studies with contemporaneous sites to determine whether cosmogramic architecture was a localized innovation or part of broader regional trends during the Formative period.

"People have this idea that certain things happened in the past — that there were kings, and kings built the pyramids, and so in modern times, you need powerful people to achieve big things," Inomata said. "But once you see the actual data from the past, it was not like that. So, we don't need really big social inequality to achieve important things."

The findings, published in Science Advances, open a fresh window on how early Maya communities shaped their world: not merely by raising earth and stone, but by transforming it into a lived map of the universe.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

atomwave

is this even true? LIDAR reveals cool stuff but how firm are the dates, could pigments have been moved later?

labcore

wow that plaza scale cosmogram? insane, communal builders, no palaces... mind blown this flips the script

Leave a Comment