5 Minutes

Recent research from the United States reveals a worrying increase in reported memory, attention, and decision-making problems — especially among adults under 40. A decade-long analysis of millions of survey responses points to social and economic forces that may be reshaping cognitive health in younger generations.

What the large study found

A research team led by Ka-Ho Wong at the University of Utah examined more than 4.5 million responses collected between 2013 and 2023 to track self-reported cognitive disability in US adults. The team defined cognitive disability as serious difficulties with memory, concentration, or making decisions, excluding respondents who reported depression.

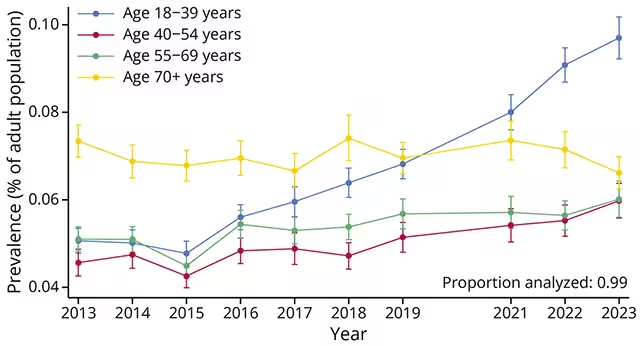

The headline figures are striking. Overall, the share of adults reporting serious cognitive difficulties increased from 5.3 percent in 2013 to 7.4 percent in 2023. But the change was most dramatic among people aged 18–39: their reported rate nearly doubled, rising from 5.1 percent to 9.7 percent over the decade.

Self-reported cognitive disability rates rose in all age groups except those aged 70 and over.

Who is most affected and why it matters

The study did more than calculate totals. It also highlighted patterns linked to income, education and race. Adults with annual incomes below US$35,000 and people with lower educational attainment saw increases larger than the average trend. Among racial and ethnic groups, American Indian and Alaska Native adults reported the highest prevalence.

Vascular neurologist Adam de Havenon of Yale University, a co-author, notes that these results point to social determinants as part of the story. He says that memory and thinking problems appear to be increasing most among people who already face structural disadvantages — an observation with major public-health and policy implications.

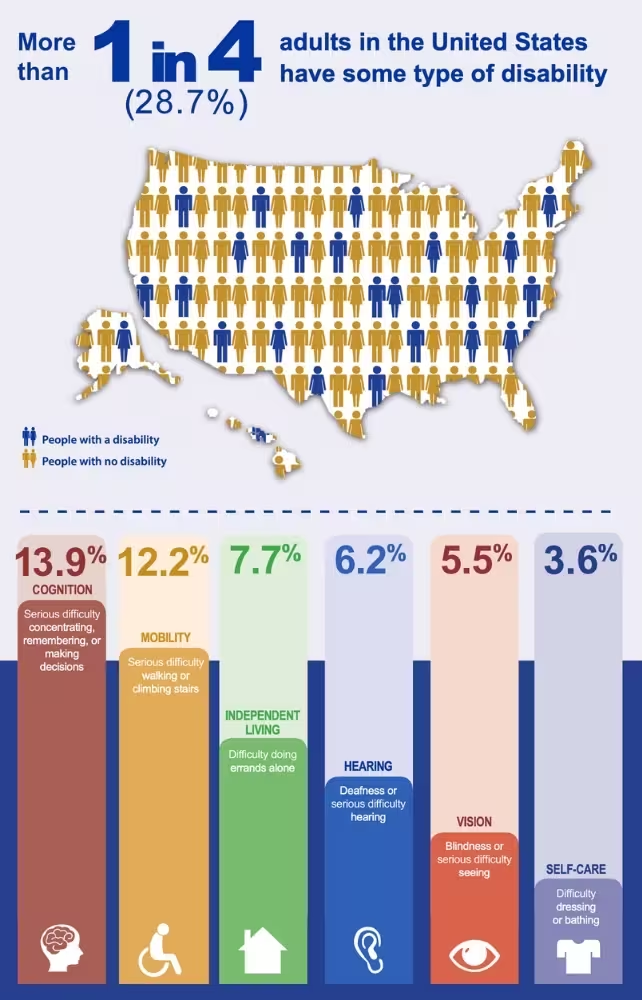

As context, annual CDC surveys estimated that 13.9 percent of US adults had a cognitive disability as of 2022, making it the most commonly reported disability on those surveys.

13.9 percent of U.S. adults have a cognitive disability. (CDC)

Possible drivers: a complex, multi-factor picture

The new analysis does not identify a single cause. Self-reported measures cannot substitute for clinical diagnostics, yet the scale of the increase demands attention. The authors and other experts point to a mix of plausible factors.

- Greater willingness to report mental-health or cognitive concerns, especially among younger adults.

- Lingering and indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on cognition and daily life.

- Rising economic insecurity, precarious work, and stressors linked to career instability.

- Increased time spent on digital devices, shifting attention patterns, and altered sleep habits.

None of these alone explains the trend. The researchers emphasize that intersecting social, economic and behavioral factors are the likeliest explanation, and that the sharp increases among younger adults are particularly concerning given long-term implications for workforce productivity, health care demand and societal well-being.

Study strengths, limits and what to watch next

The study's strengths include its large sample size and decade-long span, allowing researchers to detect changes across diverse populations and age groups. But there are limitations: cognitive status was self-reported via phone surveys rather than measured with standardized clinical testing, and depression was excluded but other comorbidities could influence responses.

Future research should pair population surveys with longitudinal clinical studies, cognitive testing, and biological measures to tease apart causal pathways. Policy responses that address socioeconomic drivers — such as access to health care, education, and stable employment — may be as critical as medical interventions.

Expert Insight

Dr. Lina Morales, a fictional public-health neurologist and science communicator, offers a practical lens: 'When large groups report more problems with memory and focus, it signals an environmental and social change as much as a medical one. We need integrated research that looks at sleep, stress, infection history and workplace conditions together. Interventions will be most effective if they combine clinical care with policies that reduce economic strain and improve mental-health access.'

In short, this Neurology study serves as an alarm bell. It does not settle the scientific debate about causes, but it does make a clear case for urgent research and policy attention to cognitive health in younger adults.

For readers and policymakers alike, that raises practical questions: How should employers, schools and health systems respond? What screening or prevention strategies could help reduce the burden of cognitive disability? The data suggest that answers will need to extend beyond clinics and into the social and economic structures that shape everyday life.

Self-reported cognitive disability rose across most age groups; however, an upward trend was not observed in senior citizens. Rates in those aged 70 and older actually declined slightly, the researchers found, from 7.3 percent in 2013 to 6.6 percent in 2023.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

cryptonav

I've seen this at work, younger teammates keep saying brain fog after late nights and nonstop screens. If true, schools and employers gotta step up, pronto.

labflux

Wait, is this even true? Self-report surveys exclude depression but what about anxiety, long covid, sleep loss... messy, could be reporting bias or a real generational shift?

Leave a Comment