5 Minutes

Specially engineered "young" immune cells generated from human induced pluripotent stem cells appear to restore some cognitive function and brain-cell health in aged mice, according to a new study from Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. The work hints at a cell-based route to counter age-related decline and certain Alzheimer’s features, although important limitations remain.

Why immune cleaners matter for aging brains

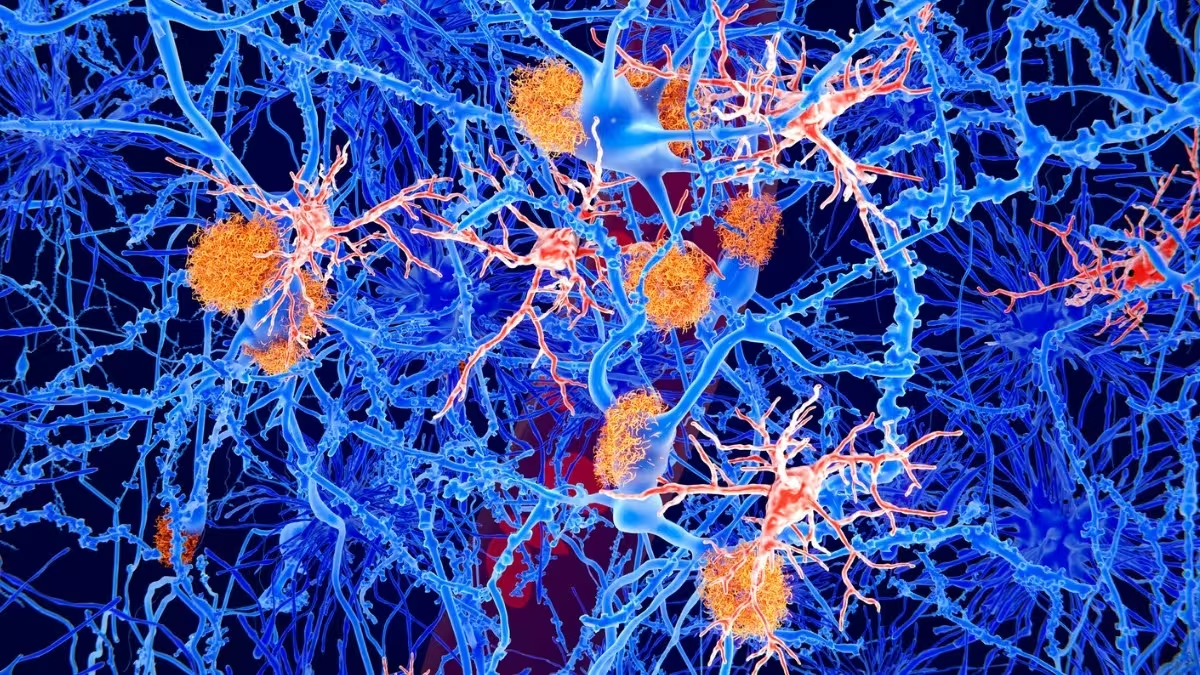

Mononuclear phagocytes are mobile immune cells that patrol the body removing waste and dead cells. In the brain, their specialized form — microglia — helps control inflammation and clear aggregated proteins. But with age, these scavengers become less efficient and more prone to promoting inflammation, a combination linked to cognitive decline and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

How the researchers built a younger immune system

Instead of transfusing young blood, the team led by Cedars-Sinai scientists created batches of mononuclear phagocytes in the lab from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). iPSCs are reprogrammed adult cells that can be coaxed to differentiate into many cell types, offering a renewable and patient-specific source of therapeutic cells. The researchers injected these engineered, youthful mononuclear phagocytes into older mice and into mouse models carrying Alzheimer’s-like pathology to test whether the cells could change cognition and brain health.

Illustration of amyloid plaques (orange) and microglia cells (red) among neurons

Encouraging improvements — but not a cure-all

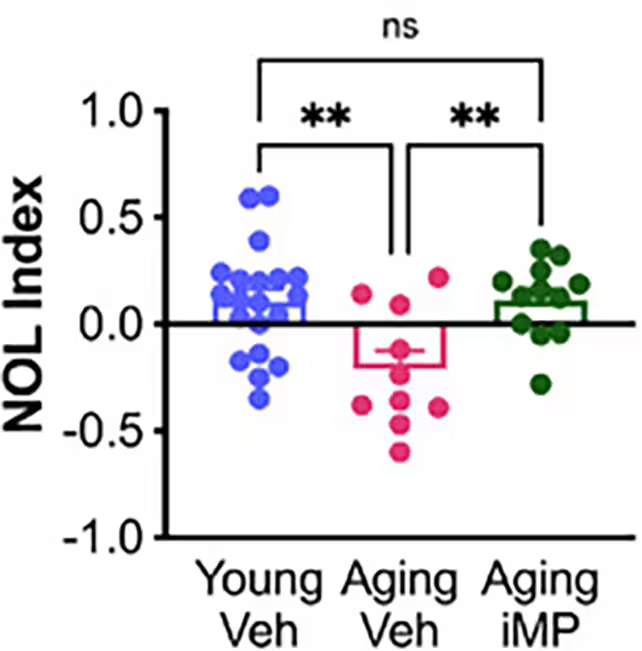

In behavioral experiments such as the novel object location task, older mice that received the lab-grown immune cells (termed "Aging iMP" in the study) performed at levels comparable to younger control animals. The treated animals also showed signs of healthier microglia and a preservation of mossy cells — a population of hippocampal neurons that supports memory function and typically declines in aging and Alzheimer's.

Lead author Alexandra Moser and colleagues report that mossy cell numbers did not fall in treated mice, suggesting a plausible link to the memory gains observed. Coauthor Clive Svendsen framed the strategy as a practical alternative to transfusing young blood: rather than giving whole plasma, the lab-made immune cells could deliver rejuvenating factors while being manufactured to clinical standards.

What actually reached the brain?

Notably, the injected immune cells did not appear to directly migrate into the animals’ brains. This points to an indirect mechanism: the circulating young mononuclear phagocytes may secrete beneficial proteins or extracellular vesicles (tiny parcels that ferry signals between cells) that cross into the brain and reduce inflammation or stimulate resident microglia. Such systemic-to-brain signaling is an active area of research in neuroimmunology.

Limitations and caveats

The benefits were most pronounced in naturally aged mice; results in the Alzheimer’s-model animals were more modest. Significant Alzheimer’s-associated damage — including amyloid-beta accumulation — was not fully reversed. And, crucially, rodent results do not guarantee similar outcomes in humans. Translating this approach will require demonstrating safety, determining dosing and delivery strategies, and showing durable benefits in larger, clinically relevant models.

Potential path to therapy and future directions

If iPSC-derived mononuclear phagocytes can be produced from a patient’s own cells, they might avoid some complications of plasma transfusion or bone marrow transplantation. The team suggests that short-term systemic treatment could be enough to re-tune immune signaling and improve cognition, opening avenues for targeted cell- or vesicle-based therapies aimed at age- and Alzheimer’s-related cognitive decline.

Expert Insight

"This study highlights the immune system as a lever for brain rejuvenation," says fictional neuroimmunologist Dr. Lena Ortiz of the Institute for Brain Health. "Even without cells entering the brain directly, peripheral immune cells can send molecular messages that reshape inflammation and support neuronal networks. The challenge now is to translate those molecular signals into a reproducible, safe treatment for people."

Where the research fits in the bigger picture

The findings add to a growing body of evidence that systemic factors — blood-borne proteins, immune cells, and extracellular vesicles — influence brain aging. Past experiments showed cognitive improvements when older animals received young blood or bone marrow; this study isolates mononuclear phagocytes as a plausible mediator and provides a manufacturable way to replicate the effect.

Next steps include mapping the active molecules released by the engineered cells, testing extracellular vesicles as a cell-free therapy, and running preclinical safety studies. If the molecular mediators can be identified, they could become targets for drugs or biologics that mimic the rejuvenating signal without requiring cell transplantation.

While far from a clinical solution to Alzheimer’s, the research offers a strategic shift: instead of trying to remove every amyloid plaque, supporting the brain’s immune environment and neuronal support cells may preserve function and delay decline.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

Tomas

hmm, interesting but are we sure the cells didn't need to enter the brain? sounds like vesicles did the job, so why not just isolate those? also animal models often fail in humans, idk.. safety and dosing??

bioNix

Whoa this is wild. Lab-made young immune cells actually improving memory in old mice? If that translates to humans it'd be huge, but they gotta ID the secret proteins and prove safety, not just flashy headlines. Fingers crossed, but cautious.

Leave a Comment