6 Minutes

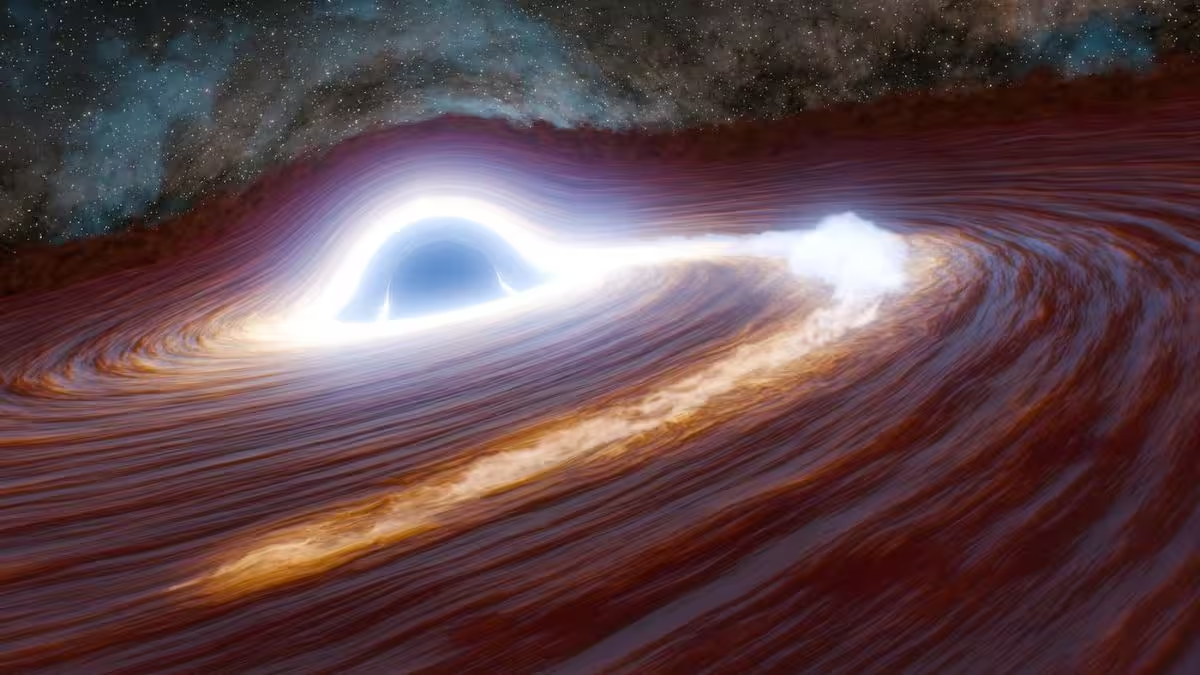

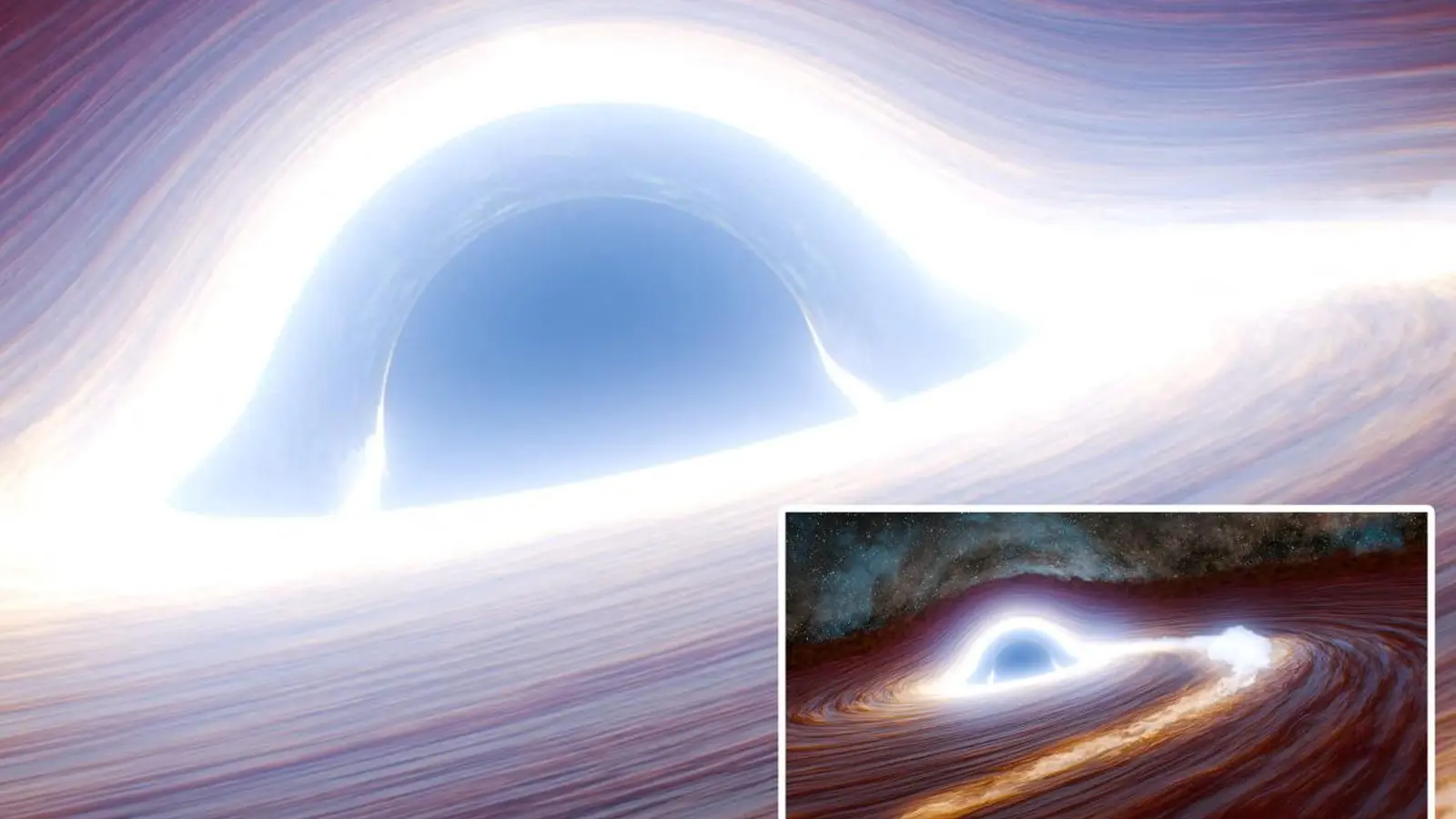

In a burst of light that traveled some 10 billion years to reach Earth, astronomers have observed the most powerful and most distant black-hole flare ever recorded. The eruption, briefly outshining entire galaxies, reached a peak luminosity equivalent to roughly 10 trillion Suns and offers a rare window into extreme physics at the centers of distant galaxies.

A flare that rewrote the record books

The source, catalogued as J2245+3743, erupted suddenly in 2018, brightening by a factor of about 40 over a few months. At its peak it was roughly 30 times brighter than the previous top active galactic nucleus (AGN) flare—an outburst colloquially known as “Scary Barbie.” By the time the discovery team submitted their analysis in March 2025, the flare had released close to 1e54 erg of energy, a scale equivalent to converting the Sun’s entire mass into electromagnetic radiation.

Lead author Matthew Graham of Caltech describes the object bluntly: its energetics and distance set it apart. “This is unlike any AGN we’ve ever seen,” he said, noting both the intensity and the remote origin of the light. The team’s interpretation: a tidal disruption event (TDE), where a supermassive black hole—estimated at roughly 500 million solar masses—tears an unlucky star apart.

Why astronomers think it was a tidal disruption event

Several cosmic phenomena can produce bright, slowly fading flares. Gamma-ray bursts tied to supernovae (the so-called BOAT, Brightest Of All Time), kilonovae from neutron star mergers, and intrinsic AGN variability can all mimic parts of a TDE light curve. To distinguish among them, the team analyzed the flare’s spectral evolution, brightness profile, and multiwavelength behavior.

The evolving light curve of J2245+3743 best matched models where a star—likely very massive, perhaps around 30 solar masses—was shredded by tidal forces near the black hole. The debris forms an accretion disk that radiates intensely as material spirals inward. Over years of monitoring the object has slowly faded but remains about two magnitudes brighter than its pre-flare baseline, indicating the black hole is still consuming the last remnants of the star.

Could the star really have been so large?

Massive stars are rare in ordinary galactic environments, but there’s a plausible mechanism for producing unusually heavy stars inside AGN disks. Astronomer K. E. Saavik Ford of the City University of New York notes that stars embedded in a dense accretion disk can accrete additional mass from surrounding material, growing larger than their more isolated cousins. That scenario would help explain how a ~30-solar-mass star could end up on a collision course with a central black hole.

Cosmological time dilation: watching the event in slow motion

One striking aspect of J2245+3743 is how long the flare appears to persist from our vantage point. Although the bright phase has been visible for more than six years on Earth, relativistic cosmological effects stretch both the light’s wavelength and the apparent duration of the event. In other words, expansion of the Universe slows the observed timeline: what lasted a couple of years close to the source may replay to us at a quarter-speed.

“It’s cosmological time dilation,” Graham explains. “The light takes so long to cross expanding space that both its color and the timing get stretched. Seven years here corresponds to about two years where the event actually happened.” Correcting for this effect is crucial for building accurate models of how TDEs progress and for comparing events across cosmic distances.

Implications for discovery and archival searches

Recognizing J2245+3743 as a TDE has practical consequences. Many past transient detections in wide-field surveys could be misclassified AGN variability or other phenomena. With refined templates that account for redshifted, time-dilated light curves, astronomers can re-sift archival data to hunt for similarly extreme events that were previously overlooked.

Finding more distant and energetic TDEs helps astronomers probe black hole demographics, the physics of accretion under extreme conditions, and stellar populations inside AGN disks. The discovery also demonstrates the value of long-term, multiwavelength monitoring programs capable of catching slow, luminous transients across cosmic history.

Where this research was published

The analysis and interpretation of J2245+3743 have been published in Nature Astronomy. The paper combines photometric and spectroscopic monitoring, modeling of the flare’s energetics, and contextual comparison with other rare cosmic explosions such as gamma-ray bursts and kilonovae.

Expert Insight

“Observations like J2245+3743 are a reminder that the Universe still holds outliers that challenge our models,” says Dr. Mira Halvorsen, a fictional astrophysicist who studies black hole accretion. “This event stretches our understanding of how much energy can be liberated during a tidal disruption—and how the environment around a black hole, such as an AGN disk, can shape both the progenitor star and the light we eventually observe.”

Long-term follow-up—across X-ray, optical, and radio bands—will reveal how quickly J2245+3743 finally fades back to its baseline and will refine estimates of the mass of the disrupted star and the black hole. For now, it stands as a record-holder: a flare brighter than anything previously documented, sent to us from the deep past and replayed in slow motion by cosmic expansion.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

mechbyte

wait, converting a Sun's mass to radiation? sounds like hyperbole, or am i missing physics here... redshift time dilation is wild tho

astroset

wow, 10 trillion suns?? that's insane. kinda spooky that we watch it in slow-mo, like cosmic replay. if true, mad props to the teams

Leave a Comment