8 Minutes

For many, human evolution feels like a chapter closed in prehistory — a story of primitive people becoming modern through tools, cities and medicine. Yet evolution did not stop once civilization began. Our genes continue to respond to environments shaped by nature and culture alike, producing new variations in skin, diet tolerance and disease resistance that affect survival and reproduction today.

Why evolution still matters for modern humans

Evolution is the process by which traits that improve survival and reproduction increase in frequency across generations. That process does not require a savannah or stone tools — it simply requires variation, heredity and selective pressures. In humans, those pressures now include cultural innovations: what we eat, where we live, how we treat disease and the technologies we use to modify our surroundings.

Think of culture as a double-edged factor. On one hand it blunts some environmental challenges: houses, clothing and heating reduce immediate exposure to cold; antibiotics and vaccines lower mortality from many infections. On the other hand, culture creates new selective environments. Farming changed diets and disease exposure, urban living concentrates pathogens, and global travel rapidly spreads novel infections.

Sunlight, skin pigment and the vitamin D trade-off

Skin pigmentation is a clear example of evolutionary change shaped by geography and lifestyle. Melanin — the pigment that darkens skin — protects against harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation. In regions with intense sunlight, darker skin lowers the risk of sunburn and skin cancers. But too much melanin can impede the skin's ability to produce vitamin D in low-UV environments.

When ancient human groups migrated out of equatorial zones into higher latitudes with less sunlight, selection favored genetic variants that reduce melanin production and improve vitamin D synthesis. This shift helped prevent rickets and supported healthy bone development in children, illustrating how the physical environment continues to sculpt human genomes.

Lactase persistence: a classic case of cultural and biological co-evolution

About 10,000 years ago, the domestication of livestock created a new resource: milk. Initially, most adult humans were lactose intolerant because the enzyme lactase declines after weaning in most mammals. But in some pastoralist populations, genetic mutations that keep lactase active into adulthood — a trait called lactase persistence — rose rapidly in frequency.

Where drinking milk provided calories, hydration and important nutrients, individuals with lactase persistence had a survival and reproductive advantage. This is a textbook example of cultural practices (dairying) altering natural selection and producing a biological response in the human population.

Diet, metabolism and local adaptations

Dietary pressures have driven many other local adaptations. For example, Arctic populations like the Inuit show genetic changes associated with fatty acid metabolism that may mitigate cardiovascular risks in diets rich in marine fats. In East Africa, some Turkana herders possess genetic variants that allow them to tolerate long periods with limited water, a trait that buffers physiological stress in arid environments.

Turkana women often dig holes several feet deep find water for themselves and their herds.

These examples highlight how food systems, subsistence strategies and climate interact with genetics. Different diets and lifestyles create different selective landscapes, yielding a mosaic of human adaptations around the globe.

Pathogens, pandemics and the evolution of resistance

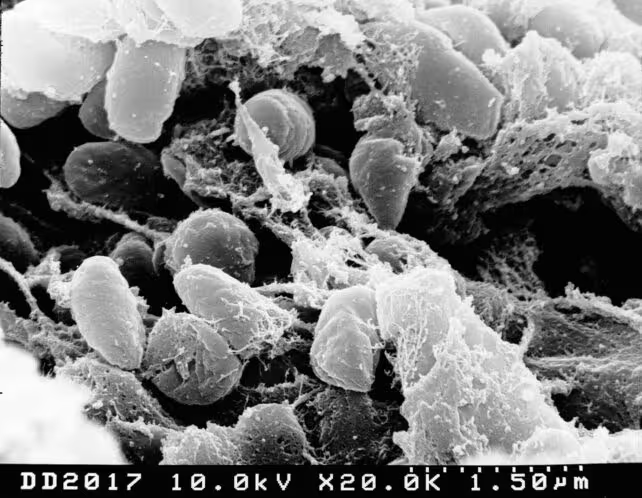

Infectious disease has long been a major selective force in human history. Epidemics can remove large proportions of a population — and survivors often carry genetic variants that confer partial resistance. After the medieval bubonic plague, for instance, some survivors likely carried alleles that improved resistance to Yersinia pestis, the bacterium that causes plague. Those alleles increased in frequency among descendants and influenced susceptibility patterns for centuries.

Scanning electron micrograph depicting a mass of Yersinia pestis bacteria (the cause of bubonic plague) in the foregut of the flea vector.

More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic revealed how modern medicine and social measures shape selective pressures. Vaccination reduced mortality dramatically, altering which infections produce strong selection. Still, genetic differences in immune response influence susceptibility and disease severity, and they may shape long-term population-level responses to novel pathogens.

Culture as an agent of evolutionary change

Culture doesn't simply shelter us from selection; it creates new niches. Urbanization, cooking, agriculture and antibiotics have all changed the selective landscape. For example, cooked food reduces the need for large jaws and certain digestive adaptations, while antibiotic use has exerted strong selection on microbes and indirectly on human microbiomes.

We can therefore think of human evolution in two interacting streams: biological evolution driven by genetic changes over generations, and cultural evolution — fast changes in behavior, technology and social organization that feed back into genetic selection. The interplay between the two is dynamic and ongoing.

Implications for health and society

Recognizing that humans are still evolving has practical implications. Medical researchers study genetic variants that influence drug metabolism, disease risk and vaccination responses. Public-health planners must consider genetic diversity when designing interventions for nutrition, infectious disease control and chronic conditions.

Moreover, awareness of how culture interacts with biology can guide policy: changes in diet and lifestyle can have long-term evolutionary consequences, and some adaptations that are beneficial in one environment may be harmful in another. Understanding local genetic variation helps tailor health care and reduce disparities.

Expert Insight

'Human evolution is not something boxed into the deep past,' says Dr. Elena Ramirez, an evolutionary anthropologist at the Institute for Human Ecology. 'We're witnessing selection in real time — from metabolic genes that influence how people process modern diets to immune genes that affect responses to emerging pathogens. The difference today is the speed and complexity of cultural change, which often reshapes selective pressures within just a few generations.'

Dr. Ramirez emphasizes that culture can both mitigate and amplify selection: 'Vaccines reduce mortality and can relax selection for certain immune traits, while changes in diet or environment can create new pressures that favor different genetic variants. The takeaway is that evolution and culture are partners in shaping who we become.'

What scientists are still learning

Research continues to map genetic variation across populations and to link specific variants with traits and environmental challenges. Large-scale genomic datasets, interdisciplinary studies combining archaeology, anthropology and genetics, and new statistical tools help trace how alleles rose or fell in frequency over time.

Future work will refine our understanding of how rapid cultural shifts — climate change, globalized diets, migration — influence evolution. The field is not just academic: it informs public health, conservation of genetic diversity and how societies adapt to environmental change.

Far from being a relic of the past, human evolution is an active process shaped by our environments and the cultures we create. As we change the world, we continue to change ourselves — with consequences that matter for health, equity and the future of our species.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

Lukas

is this even true? evolution now, in a few generations? feels sketch, medicine hides selection but culture selects too, hmm

genoFlux

wow didnt expect evolution to be this active today. skin, milk, immune tweaks... wild, but also worrying for health equity, tbh

Leave a Comment