6 Minutes

Finasteride has long been a go-to prescription for men facing androgenetic alopecia, promising slowed hair loss and in many cases visible regrowth. But recent regulatory updates and accumulating patient reports have sharpened focus on a troubling question: can this effective drug also trigger serious mental-health side effects?

How finasteride works and why it helps hair

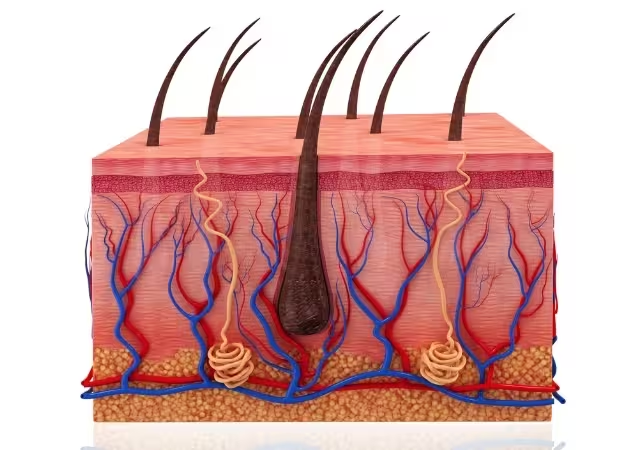

Finasteride treats androgenetic alopecia — commonly called male pattern baldness — by targeting a hormone pathway that affects hair follicles. In the body, testosterone is converted by an enzyme called 5-alpha-reductase into dihydrotestosterone (DHT). DHT binds to scalp hair follicles and shortens their growth cycle, a process called follicle miniaturization, which produces thinner, shorter hairs over time.

By inhibiting 5-alpha-reductase, finasteride reduces DHT levels by roughly 60–70% in many men. The usual dose for hair loss is an oral 1 mg tablet taken daily; higher doses (5 mg) are used for benign prostatic hyperplasia, not baldness. Because the drug acts on hormonal conversion, it is not routinely prescribed to women for this indication.

What clinical trials and post-market monitoring reveal

Initial clinical trials that led to finasteride’s approval focused on efficacy — stopping hair loss and encouraging regrowth — and documented common side effects such as decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, and reduced semen volume. Those sexual side effects are well established and listed in prescribing guidance.

However, mental-health effects were not prominent in early randomized trials. As finasteride moved into wider use over decades, spontaneous reports and observational studies began to accumulate descriptions of depressed mood, anxiety and, in some cases, suicidal thinking. Because these reports largely rely on self-reporting and observational data, establishing direct causation is challenging: depression itself is common, and hair loss can contribute to psychological distress independently.

Regulatory updates: Europe and the U.S.

Regulators have recently taken more definitive steps. In May 2025 the European Medicines Agency (EMA) concluded that suicidal thoughts are a confirmed adverse effect of finasteride and advised patients and prescribers to be aware of the risk of depressed mood and depression. In the U.S., the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warning in April 2025 noting that topical formulations of finasteride — compounded versions applied to the scalp — can carry similar mental-health risks to the oral formulation, including depression and anxiety.

These regulatory actions do not mean every user will experience these effects. Rather, they reflect a precautionary stance based on reported cases and the principle that patients should be informed and monitored for mood changes while taking the drug.

Assessing personal risk and spotting warning signs

There is no single test to predict who will develop mood symptoms while on finasteride. Known risk factors for depression — a personal or family history of mood disorders, recent major life stressors, or concurrent medication use that alters mood — should prompt a careful discussion with a clinician before starting treatment.

Red flags to watch for

- Persistent low mood or hopelessness

- New or worsening anxiety

- Loss of interest in activities you usually enjoy

- Thoughts of self-harm or suicide

If you notice these symptoms after starting finasteride, contact your healthcare provider promptly. For mild changes, clinicians may suggest pausing the medication and monitoring mood, or combining the medication with mental-health support. For more severe symptoms, discontinuing finasteride and seeking rapid psychiatric assessment is often advised.

Alternatives and practical choices

Not everyone who seeks treatment for hair loss needs to use finasteride. Topical minoxidil is a well-established first-line treatment available over the counter in many countries. It stimulates hair growth through a different mechanism and tends to have fewer systemic effects because it’s applied to the scalp. Local irritation is the most common complaint; reports linking minoxidil to mood changes are rare.

Dutasteride, another 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor, works similarly to finasteride and may carry comparable mental-health risks, so it is not usually recommended as an alternative for patients who experienced adverse mood effects on finasteride.

For some men the best approach combines treatments — for example, topical minoxidil with lifestyle measures that support scalp and overall health — while others may opt for non-pharmacological options like hair transplants.

Expert Insight

“Finasteride remains one of the most effective medical treatments for male pattern hair loss,” says Dr. Aaron Mitchell, a fictional dermatologist and hair-loss researcher. “But medicine is about balancing benefits and risks. Clinicians should screen for psychiatric vulnerability before prescribing and maintain open follow-up: ask directly about mood and suicidal thoughts, because patients don’t always volunteer that information.”

Dr. Mitchell adds that informed consent matters: “A patient who understands potential sexual and mental-health side effects can make a more confident, monitored choice — and that monitoring is the safety net we need to catch rare but serious outcomes early.”

Practical takeaways for patients and prescribers

- Discuss mental-health history with your clinician before starting finasteride.

- Monitor mood regularly; report any persistent low mood, anxiety, or suicidal thoughts immediately.

- If symptoms appear after beginning treatment, pausing the drug is a reasonable first step under medical guidance; most side effects improve after cessation, though a minority report persistent symptoms.

- Consider topical minoxidil or non-drug options if systemic hormone effects are a concern.

Understanding the balance between efficacy and safety is essential. For many men, finasteride offers meaningful hair regrowth and improved quality of life. For a smaller group, however, the risk to mental well-being means careful decision-making, informed consent, and active monitoring are non-negotiable parts of responsible care.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

Armin

Had a mate take finasteride, mood tanked after a few months. Doc paused it, mood improved quick. Not proof but if you're starting, be cautious

atomwave

Is this even true? Regulators now warn but causation still fuzzy. Hair loss hurts the psyche too, so messy. Anyone got solid data?

Leave a Comment