5 Minutes

A novel hybrid immune-cell therapy has fully prevented and reversed type 1 diabetes in mice without long-term immunosuppression, according to researchers at Stanford School of Medicine. By creating a mixed immune system containing cells from both donor and recipient, the team restored insulin-producing islets and blocked the autoimmune attack that causes the disease.

Why this approach matters: resetting the immune system and replacing islets

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disorder in which the body's immune system mistakes pancreatic beta islet cells for invaders and destroys them. Without those cells, insulin production collapses and blood sugar regulation fails. Conventional islet transplantation can restore insulin production, but transplanted cells face the same autoimmune attack — and patients often need life-long immunosuppressive drugs to prevent rejection.

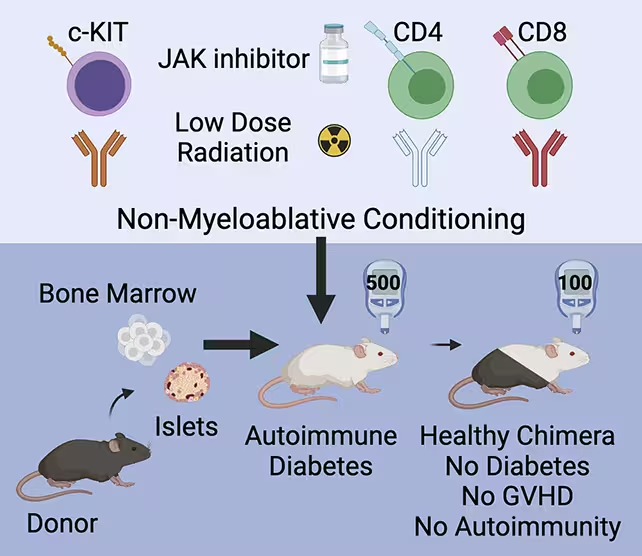

The Stanford team took a different route: instead of only replacing islets, they prepared recipients so their immune systems could accept donor cells and operate in balance with them. Their hybrid strategy mixes blood-forming (hematopoietic) stem cells and donor islet cells with a conditioning regimen that subtly reboots the recipient immune system. The result is a chimeric or hybrid immune system containing both recipient and donor immune cells that tolerates the transplanted islets without ongoing immunosuppression.

How the experiment worked: conditioning, transplant and tolerance

In the study, prediabetic and diabetic mice received a brief conditioning protocol: a short course of an immune system inhibitor, low-dose radiation, and select antibodies designed to reduce specific immune populations but not wipe the system clean. Donor blood stem cells were infused alongside healthy donor islets.

Animals were given a conditioning treatment to prepare their immune systems for the cell transplant.

That mild conditioning allowed donor stem cells to engraft and produce a population of donor-derived immune cells that coexisted with the host's immune cells. Rather than triggering graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) — a common complication when cells from one individual attack another — the hybrid animals maintained immune balance. Transplanted islets were protected, and beta cell function recovered, normalizing blood glucose in mice with established diabetes and preventing disease in prediabetic animals.

Key results and scientific implications

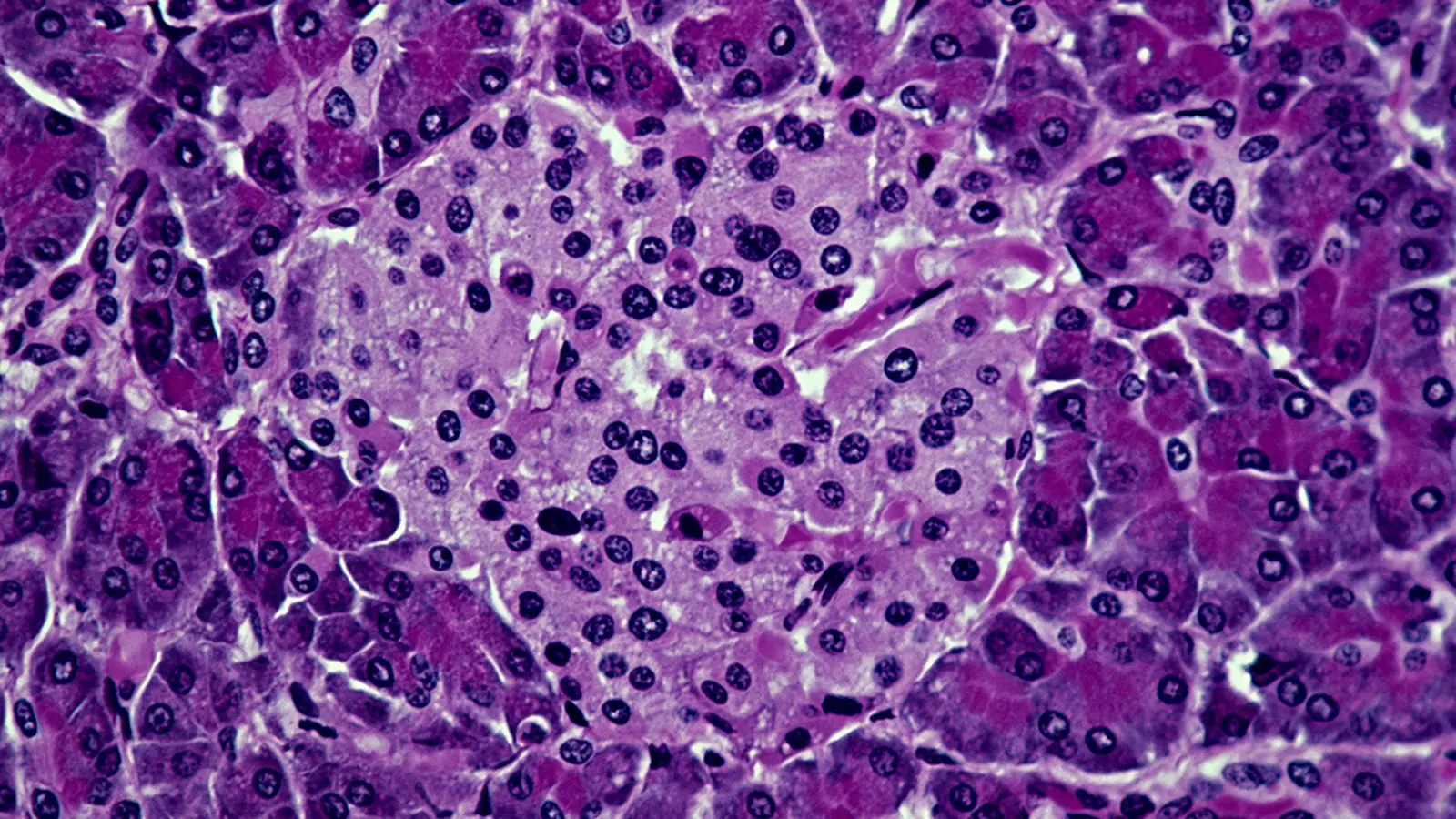

The outcomes are striking: the therapy prevented diabetes in high-risk mice and reversed full-blown disease in others. Importantly, none of the treated animals developed graft-versus-host disease during the observation period, and immune function returned to normal aside from tolerance to the donor islets. A small subset of islet cells showed mild inflammation yet were not destroyed — an encouraging sign that tolerance mechanisms, not blanket suppression, were at work.

Senior author Seung Kim of Stanford described the approach as transformative, suggesting similar hybrid strategies might extend to autoimmune diseases and solid-organ transplants. Mixing donor and recipient immune cells to induce tolerance is not entirely new — earlier transplant studies, including prior work from this group, have shown the principle can work — but the application to type 1 diabetes and the combination with islet replacement is a major step forward.

Challenges ahead: supply, scaling and human translation

Despite the promising results, significant hurdles remain before human patients can benefit. Donated human islets are rare and typically available only post-mortem; clinical protocols would need matched blood stem cells alongside the islets for the hybrid strategy to work as designed. Researchers are exploring ways to increase survival of donated cells and investigating whether islets could be derived from pluripotent stem cells in the lab to provide a reliable supply.

Other open questions include the optimal number of donor stem and islet cells required, the precise conditioning regimen that balances efficacy with safety, and long-term durability of tolerance. The team notes that the core clinical steps used to create hybrid immune systems are already applied in other medical contexts, which could accelerate trial design for people with type 1 diabetes.

Expert Insight

"The dual strategy of replacing lost beta cells while re-educating the immune system addresses both sides of the problem," says Dr. Laura Chen, an immunologist and transplant researcher unaffiliated with the study. "If the hybrid immune state proves durable in humans, it could reduce or eliminate the need for chronic immunosuppression — a huge clinical advantage."

The authors are cautious but optimistic. They emphasize that while the results do not yet translate directly to humans, the mechanistic concept — creating controlled chimerism to induce antigen-specific tolerance — is already present in clinical practice for other conditions. With further optimization and scaled cell production, this hybrid approach could shift how we think about autoimmune disease and cell-based therapy.

For now, the research represents meaningful progress: a laboratory demonstration that autoimmunity and cell replacement can be addressed in tandem. The path to human trials will require solving logistical and biological puzzles, but the prospect of a curative strategy for type 1 diabetes has moved demonstrably closer.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

DaNix

This sounds promising but is it reproducible in humans? donor islet supply sounds like a bottleneck, and conditioning risks... hmm.

bioNix

wow this is wild, mice cured?? if that scales to humans it'd change everything. curious about side effects tho, long term?

Leave a Comment