3 Minutes

Researchers at ETH Zurich have built nanoOLED diodes so tiny they disappear to the naked eye. At roughly 100 nanometers across, these emitters are hundreds of times smaller than typical biological cells and could redefine display resolution and optical control in compact devices.

Tiny diodes, gigantic pixel density

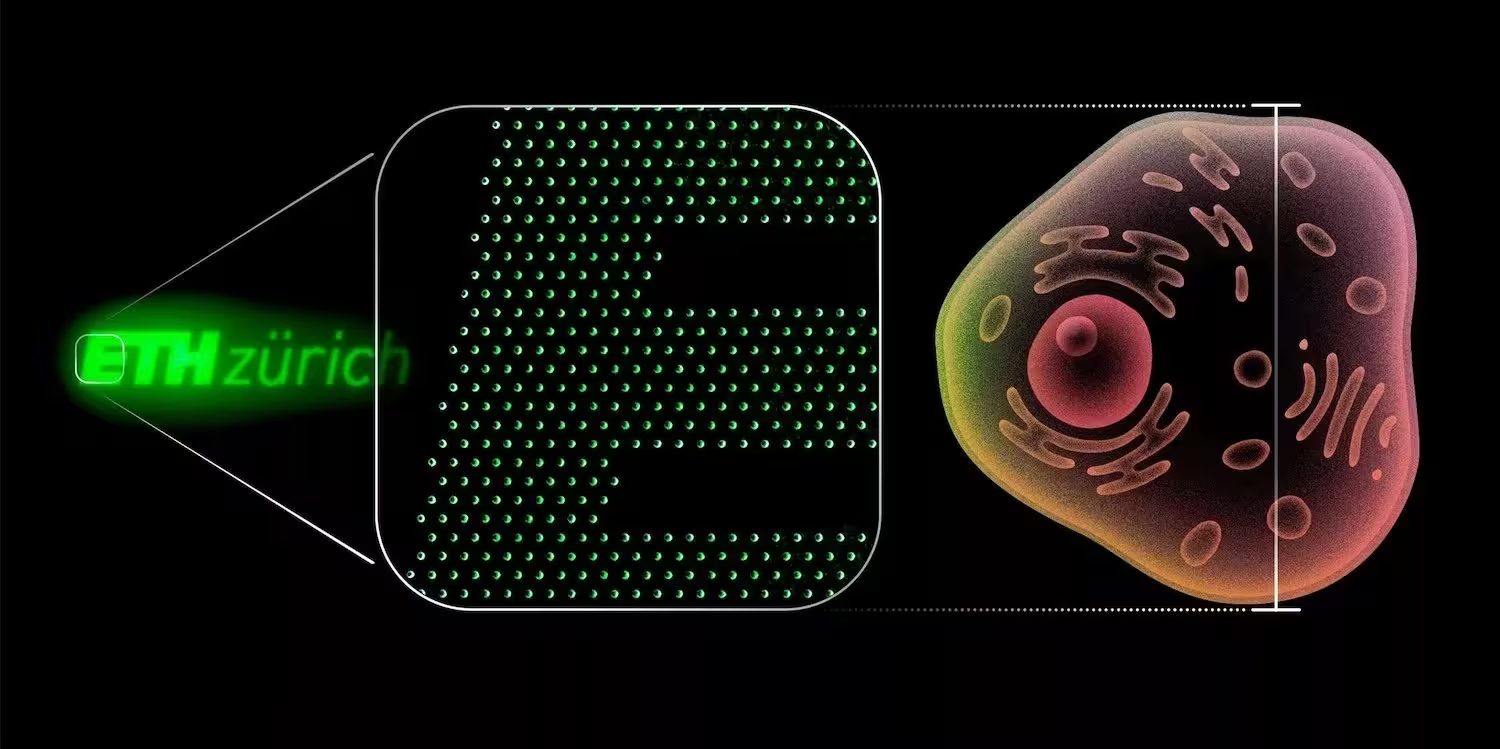

The team reports diodes with diameters near 100 nm — about 50 times smaller than the most advanced pixels used in industry today. To demonstrate scale, researchers recreated the ETH Zurich logo using 2,800 of these diodes; the entire logo occupied just 20 micrometers, a footprint comparable to a single human cell.

That packing density translates into an astonishing 50,000 pixels per inch (ppi), roughly 2,500 times denser than current displays. Imagine a VR headset with so much detail the screen-door effect vanishes entirely — that's the kind of leap this technology promises.

How physics makes ultra-small pixels work

Beyond miniaturization, the breakthrough hinges on light-wave physics. When light sources sit closer than about half a wavelength (roughly 200–400 nm), their waves interact — interfering and reinforcing in patterns that can be steered without moving parts. This circumvents traditional optical limits known as the diffraction limit and enables electronic control of light direction simply by arranging the nanoOLEDs.

Dr. Tommaso Marcato, a lead researcher, likens the effect to "throwing two stones into a calm pond," where the ripples meet, reinforce or cancel each other. By designing the layout of the emitters, the team can steer and focus light electrically, rather than mechanically.

What this enables next

- VR and AR: Ultra-high pixel density could deliver glasses-like headsets with lifelike clarity and no visible pixels.

- Microscopy and lab tools: NanoOLED arrays can serve as precision illumination sources for advanced microscopes.

- Biosensing: Compact, high-resolution light arrays could help detect single-cell neural signals or power ultra-sensitive diagnostics.

- Holography: True 3D holographic displays become more achievable when light can be generated and steered at the nanoscale.

These findings, published in Nature Photonics, mark a step toward displays and optical systems that were previously theoretical. While commercialization will require overcoming manufacturing and integration challenges, the potential applications span consumer electronics, medical devices, and scientific instrumentation.

Leave a Comment