4 Minutes

Researchers have found a surprising new route to create insulin-producing cells: by reprogramming human stomach tissue. Using lab-grown stomach organoids and a genetic 'switch,' scientists converted gastric cells into beta-like cells that can secrete insulin and help control blood sugar in diabetic mice.

From stomach organoids to insulin factories

Type 1 diabetes occurs when the pancreas loses or destroys the specialized beta cells that make insulin, leaving patients dependent on lifelong insulin injections and glucose monitoring. To replace lost beta cells, researchers have explored many avenues — from stem cell–derived islets to donor transplants — but each approach faces obstacles such as immune rejection, limited donor tissue, and complex manufacturing.

Now, an international team led by Xiaofeng Huang (Weill Cornell Medicine, USA) and Qing Xia (Peking University, China) adapted a clever alternative: take advantage of cells already present in the body. Building on earlier mouse experiments, the researchers grew miniature human stomach models called organoids that mimic key features of gastric tissue. They then introduced a programmable set of genetic factors — effectively a switch — that can coax those stomach cells to adopt a beta-like identity when activated.

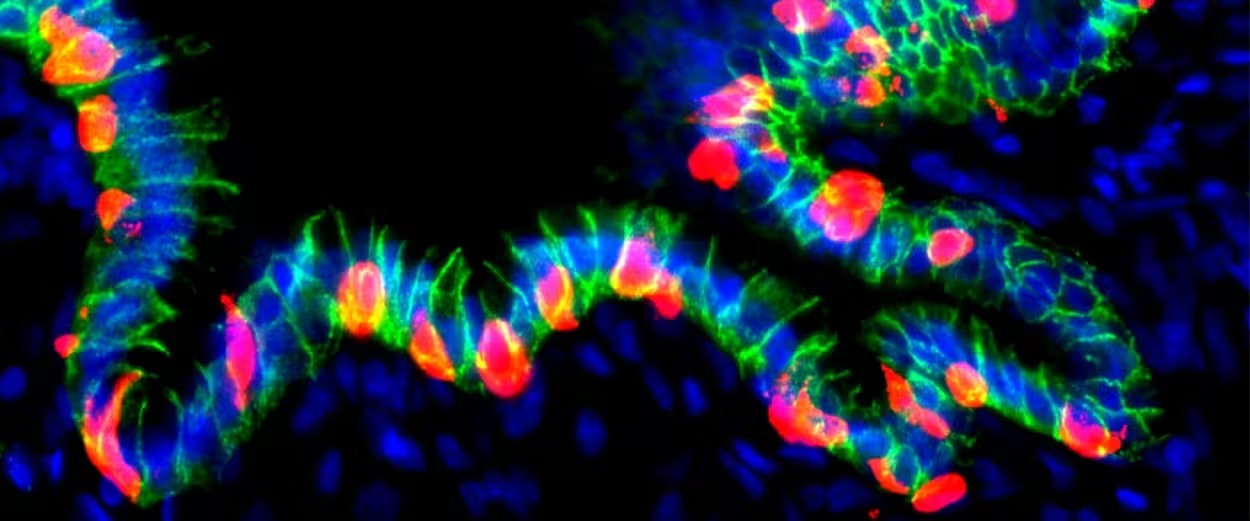

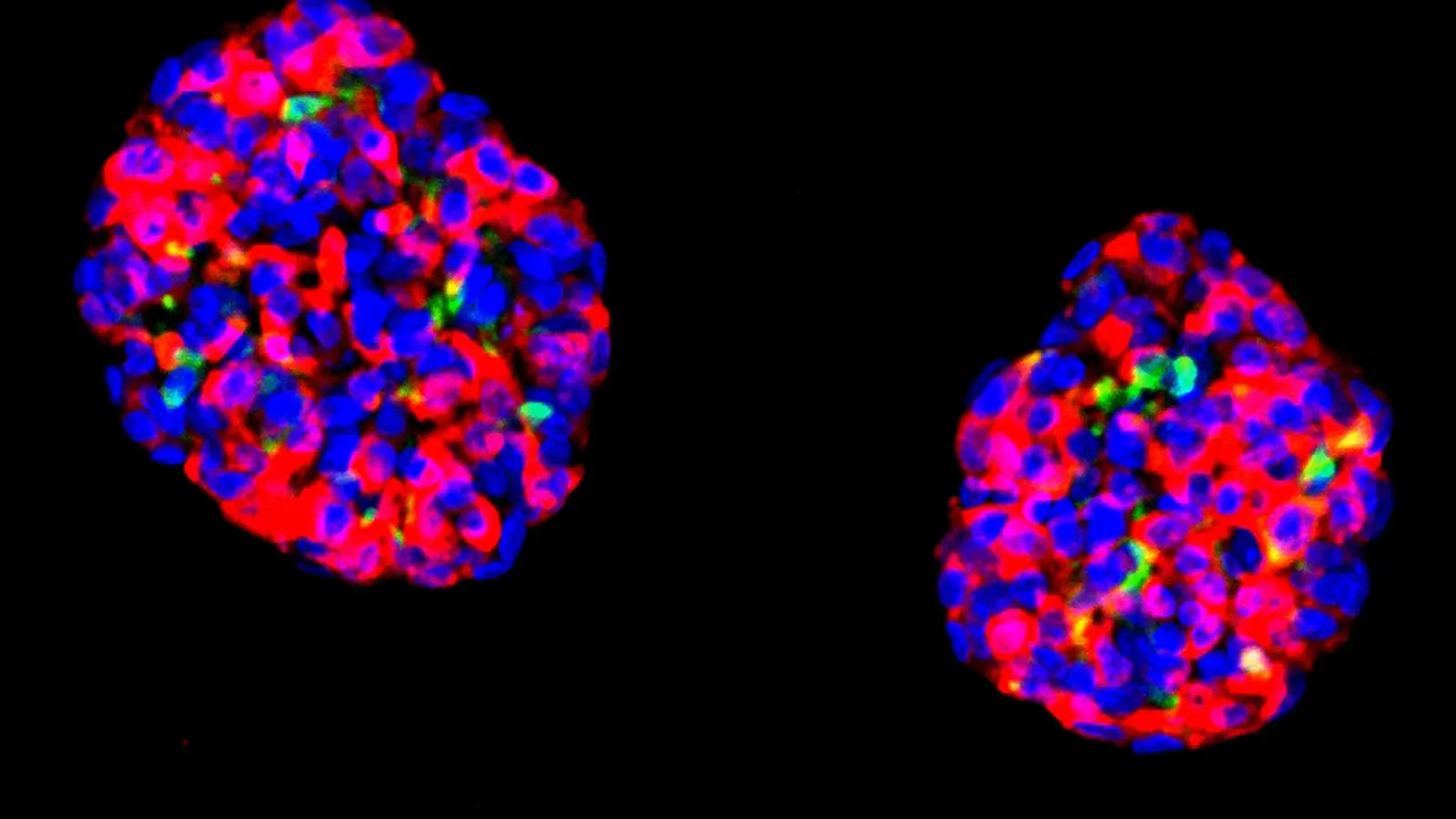

Grafted hGO-NPM generates insulin+ cells

How the reprogramming worked

- The team cultured human gastric organoids in vitro to obtain a renewable source of cells.

- They engineered the organoids with a controllable genetic program that triggers beta-cell genes and protein expression.

- After transplanting these engineered organoids into the abdomen of mice, the tissues integrated with local blood vessels and survived for months.

- When the switch was flipped, the human-derived gastric cells began producing insulin and showed genetic and protein markers similar to pancreatic beta cells.

Why this matters for Type 1 diabetes

In diabetic mice, insulin released by the converted human stomach cells helped regulate blood glucose and improved symptoms — a key proof of concept. Because stomach tissue is accessible via minimally invasive procedures (for example, endoscopy), this approach raises the possibility of reprogramming a patient’s own cells in situ, avoiding donor shortages and reducing the risk of immune rejection.

Of course, major hurdles remain. The team reports the findings in Stem Cell Reports (November 6), but stresses safety, durability, and long-term function must be demonstrated before human trials. Important questions include controlling the reprogramming precisely, preventing unintended cell behavior, and ensuring the immune system won’t attack the new insulin-producing cells.

What comes next: paths and challenges

Future work will focus on refining the genetic switch, testing longer-term survival and function, and developing strategies to protect converted cells from autoimmune attack typical of Type 1 diabetes. If successful, gastric reprogramming could join other regenerative strategies — such as stem cell–derived islets and encapsulation technologies — in a growing toolkit aimed at restoring physiological insulin production.

For now, this study offers an intriguing proof of concept: the stomach, normally unrelated to blood sugar control, can be repurposed into an insulin source. That shift in perspective opens new possibilities for cell-based diabetes therapies and highlights the creative approaches scientists are using to tackle chronic disease.

Source: scitechdaily

Leave a Comment