5 Minutes

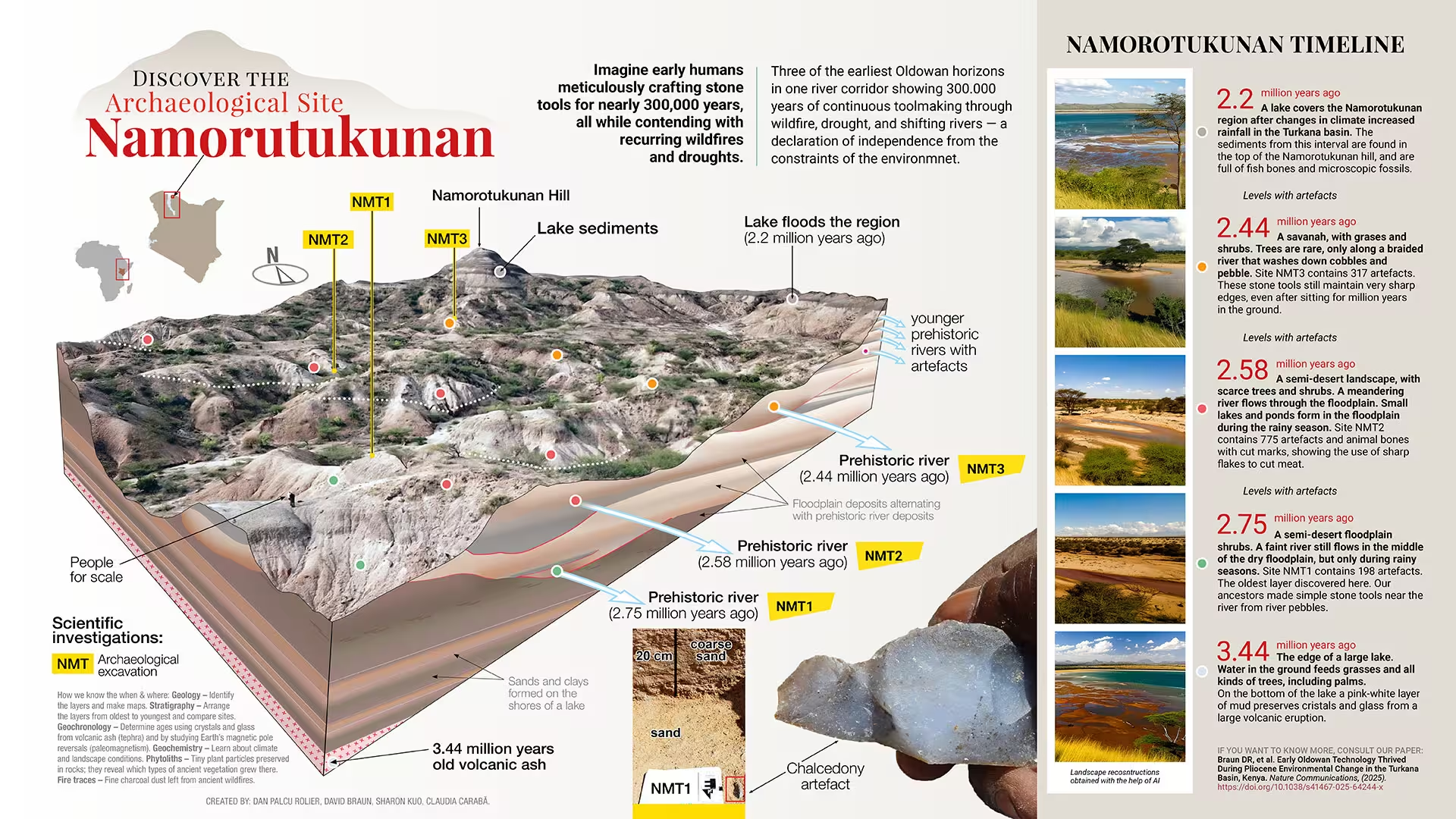

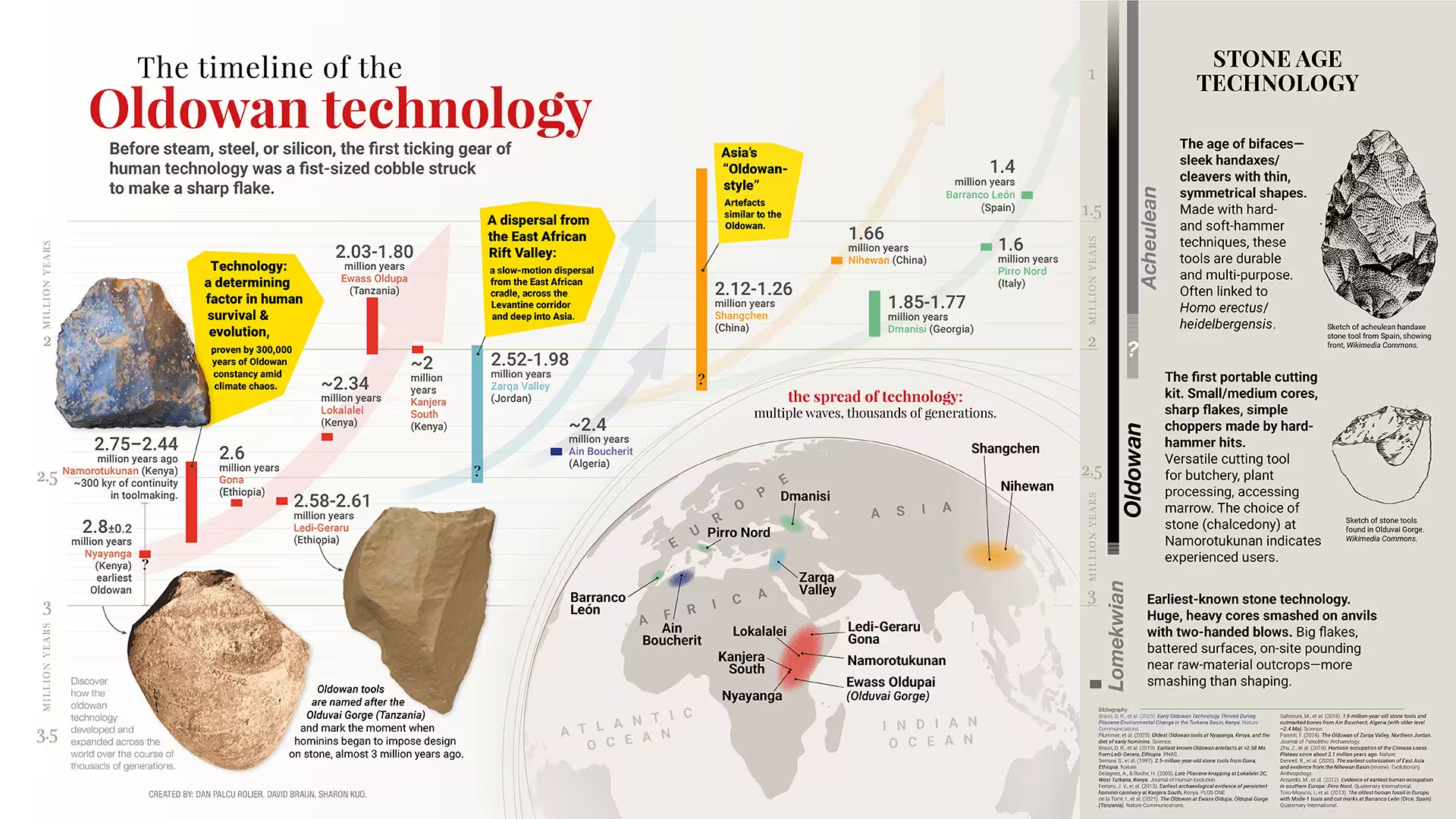

Imagine a single toolmaking tradition surviving for nearly 300,000 years while rivers shifted course, fires swept through the landscape, and long dry spells tightened the earth. Excavations at the Namorotukunan site in Kenya’s Turkana Basin reveal that early hominins repeatedly produced the same sharp-edged stone implements between about 2.75 and 2.44 million years ago — a signal of technological continuity that changes how we think about early human adaptation.

What the rock record reveals

An international research team assembled one of the most complete Oldowan tool records yet discovered. The stone flakes and cores from Namorotukunan are simple in form but consistent in manufacture: they served multiple functions and were produced by skilled hands across many generations. Rather than a one-off innovation, the pattern points to a durable cultural practice — a kind of early technology that hominins relied on while their world changed dramatically.

How scientists dated and reconstructed the environment

Dating the site required a toolkit of modern methods. Volcanic ash layers (tephra) provided primary time markers. Magnetostratigraphy — the study of preserved magnetic signals in sediments — helped position those layers in Earth’s polarity timeline. Geochemical sourcing of raw stone revealed where toolmakers obtained material, and microscopic plant fossils (phytoliths) traced shifts from wetlands to open grassland and semidesert. Combined, these techniques built a high-resolution environmental story that frames the tools in context.

Why multiple methods matter

Each method checks the others. Tephra dates anchor sediments in time; magnetostratigraphy fills gaps between ash layers; geochemistry ties tools to raw-material landscapes; plant microfossils show how vegetation — and therefore available food — evolved. Together they make the long span of tool use at Namorotukunan a robust finding, not a quirk of preservation.

Resilience, diet and behavioral implications

The archaeological signature includes cutmarks on bones that match the use-wear and edge morphology of the stone tools. That linking of tools to butchery suggests these hominins broadened their diet to include meat and marrow — a shift with big nutritional and social consequences. In volatile climates, a reliable set of tools that opened new food resources could be a major survival advantage.

"This site reveals an extraordinary story of cultural continuity," says David R. Braun, the study’s lead author and an anthropology professor at George Washington University. "What we’re seeing isn’t a one-off innovation — it’s a long-standing technological tradition."

Scientific background: Oldowan technology and the Turkana Basin

Oldowan refers to some of the earliest known stone tool industries, characterized by simple flakes and cores struck from cobbles. The Turkana Basin has long been central to paleoanthropology because its sediments preserve long sequences of fossils, artifacts, and environmental proxies. Finding an extended Oldowan record here strengthens the idea that early stone technology was a foundational, repeatable strategy — not just isolated sparks of innovation.

Key discoveries and broader significance

- Longevity of practice: Toolmaking styles remained remarkably consistent across roughly 300,000 years, implying knowledge transfer between generations.

- Environmental resilience: Tools persisted through episodes of fire, aridity, and landscape change, suggesting technological steadiness amid ecological instability.

- Dietary expansion: Cutmarks and contextual evidence point to sustained meat use, aligning technology with nutritional shifts in early hominin lifeways.

Expert Insight

"When you put the dating, the environmental record, and the tool evidence together, a clear picture emerges: early hominins used technology as a stabilizing strategy," says Dr. Maya Chen, a paleoecologist not involved in the study. "This research helps explain how cultural behaviors — making and using tools — could buffer small-brained hominins against rapid ecological change."

Findings from Namorotukunan invite a reassessment of how early technology influenced survival strategies and social learning. If a simple, consistent toolkit could persist and spread across generations in such a turbulent context, it suggests that cultural transmission and behavioral flexibility were already important threads in the deep history of our lineage.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

Marius

If that's real then the dating looks crucial. tephra, magnetostratigraphy etc, cool but complex. did they rule out reworking of layers, or is that accounted for.. curious

labcore

wow, nearly 300k years of the same toolkit? mind blown. shows culture way earlier than i thought, weird and cool. makes me think about how social learning started...

Leave a Comment