6 Minutes

New research suggests that a handful of gargantuan, short-lived stars—each thousands of times the mass of the Sun—left chemical fingerprints on the universe’s oldest star clusters and helped shape the first galaxies.

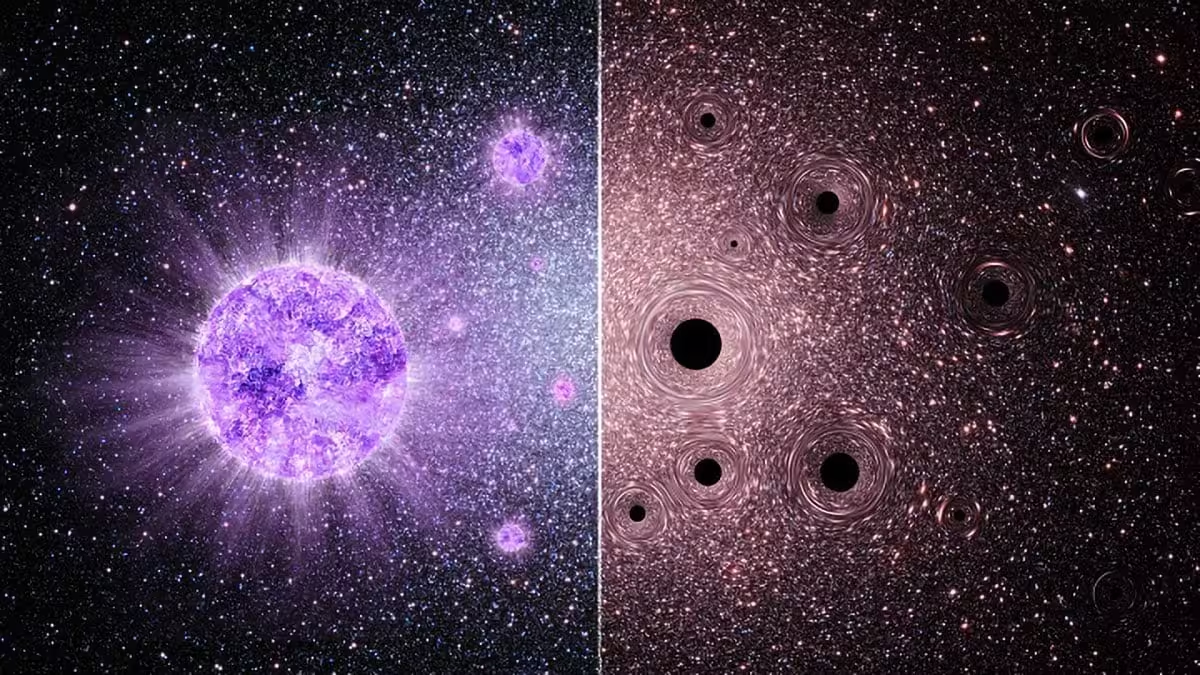

On the left, an artist’s impression of a globular cluster near its birth, hosting extremely massive stars with powerful stellar winds that enrich the cluster with elements processed at extremely high temperatures. On the right, an ancient globular cluster as we observe it today: surviving low-mass stars retain traces of the winds from those extremely massive stars, which have since collapsed into intermediate-mass black holes. Credit: Fabian Bodensteiner; background: image of the Milky Way globular cluster Omega Centauri, captured with the WFI camera at ESO’s La Silla Observatory.

Ancient star clusters as chemical time capsules

Globular clusters are dense, spherical assemblies of stars that orbit galaxies, including our own Milky Way. Typically containing hundreds of thousands to millions of stars, many of these clusters formed more than 10 billion years ago—soon after the Big Bang—and act as fossil records of early star formation and chemical evolution.

Yet globular clusters have posed a stubborn puzzle: their stars show unusual and recurring abundance patterns. Instead of uniform chemical compositions, many clusters host multiple stellar populations with unexpected levels of helium, nitrogen, sodium, oxygen, magnesium and aluminium. For decades astronomers have debated what produced these anomalies, and how such processed material could be incorporated into later generations of stars inside the same compact cluster.

How extremely massive stars could solve the mystery

An international team led by ICREA researcher Mark Gieles (Institute of Cosmos Sciences, University of Barcelona) has now proposed a model that ties these chemical oddities to extremely massive stars (EMS)—stars with masses between roughly 1,000 and 10,000 times that of the Sun. Published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, the study adapts an "inertial-inflow" model of star formation to the dense, turbulent conditions of the early universe.

In those extreme environments, gas flows and turbulence concentrate mass quickly, enabling the creation of a few EMSs inside the largest protoclusters. These giants burn hydrogen at extraordinarily high central temperatures and drive powerful stellar winds loaded with the products of high-temperature nuclear reactions. When those winds mix with the surrounding pristine gas, they seed the next generation of stars with distinct chemical fingerprints.

"Our model shows that just a few extremely massive stars can leave a lasting chemical imprint on an entire cluster," says Mark Gieles. The scenario naturally explains how processed material—produced early and rapidly—becomes incorporated into later-born, lower-mass stars that we still observe today.

Fast processes, clean gas: timing matters

One crucial aspect of the model is speed. The EMS-driven enrichment happens on timescales of about one to two million years—remarkably fast compared with the lifetimes of massive stars that explode as supernovae. Because the winds and chemical mixing occur before the first supernovae detonate, the enriched gas stays free from heavy-element contamination that would otherwise erase the distinctive abundance patterns.

Researchers Laura Ramírez Galeano and Corinne Charbonnel of the University of Geneva note that nuclear reactions in the cores of extremely massive stars were already known to generate the right mix of elements. "We now have a model that provides a natural pathway for forming these stars in massive star clusters," they add, pointing to the inertial-inflow mechanism as a plausible formation route.

From star clusters to galaxies and black holes

The implications reach beyond individual clusters. The same EMS-rich clusters could be common building blocks of the earliest galaxies. Observations by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have revealed high-redshift galaxies with unusually strong nitrogen emission—signals that match the chemical output expected from EMS-enriched systems.

"Extremely massive stars may have played a key role in the formation of the first galaxies," says Paolo Padoan (Dartmouth College and ICCUB-IEEC). Their intense luminosity and chemical processing provide a natural explanation for the nitrogen-enriched proto-galaxies JWST is beginning to uncover.

When EMSs exhaust their fuel they are unlikely to explode as ordinary supernovae. Instead, many models predict a direct collapse into intermediate-mass black holes (IMBHs)—objects with masses of a few hundred to a few thousand suns. These IMBHs are promising sources of gravitational waves when they merge, and could seed the growth of the supermassive black holes found in galaxy centers today.

Related technologies and future prospects

The idea that EMSs influenced early galaxy chemistry can be tested with next-generation observations. JWST spectroscopy, ground-based surveys targeting stellar populations in old globular clusters, and gravitational-wave detectors searching for IMBH merger signals will all provide complementary constraints. Improved simulations of turbulent gas inflows and stellar wind mixing are also essential to refine the model’s predictions.

Expert Insight

Dr. Ana Ribeiro, an astrophysicist specializing in early star formation, comments: "This model elegantly links dynamics, nucleosynthesis and observational signatures. If EMSs were common in the first massive clusters, we should see coherent chemical patterns across many old clusters and a population of intermediate black holes lurking in their cores. It's an exciting time—JWST and gravitational-wave astronomy may finally let us test these ideas."

Whether EMSs turned the chemical dials of nascent galaxies or simply added a noteworthy footnote to cosmic history, the new model offers a cohesive framework. It connects the physics of star formation, the detailed chemistry locked in ancient stars, and the origins of black holes—opening fresh paths for observation and theory as we probe the universe’s first billion years.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

DaNix

Are we sure these 1k-10k Msun stars actually form that often? Paper sounds neat but formation efficiency seems optimistic, needs more sims and obs, no?

astroset

wow didnt expect gargantuan stars to be the culprits... IMBH seeds, JWST nitrogen lines, mind blown 🤯 If true, cosmic history just got way weirder

Leave a Comment