5 Minutes

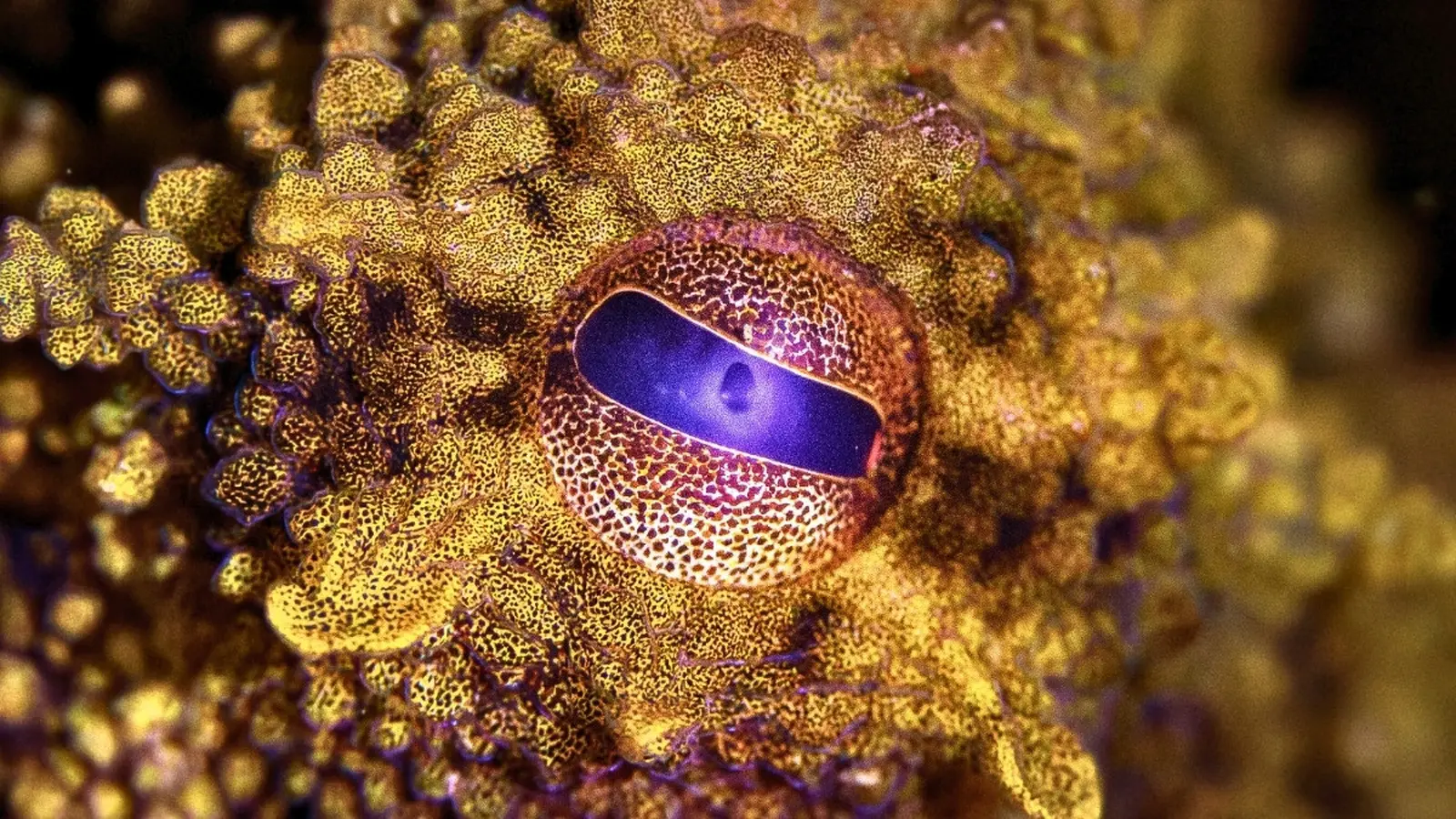

Octopuses, squids and their cephalopod relatives are famous for vanishing acts that look like magic. The secret behind their color shifts includes a rare pigment called xanthommatin — until recently, nearly impossible to obtain at scale. A team led by researchers at UC San Diego has now engineered bacteria to churn out this pigment efficiently, opening new doors for understanding cephalopod camouflage and for greener chemical manufacturing.

How researchers persuaded microbes to make a cephalopod pigment

Producing xanthommatin in the lab has long been impractical. Collecting it from animals is inefficient and chemical synthesis routes are low-yield and costly. To solve that bottleneck, scientists turned to an emerging approach in synthetic biology: program microbes to manufacture complex molecules.

Rather than simply inserting pigment-making genes and hoping for the best, the team developed a strategy they call "growth-coupled biosynthesis." In plain terms, they rewired bacteria so that survival depended on producing xanthommatin. The engineered cells could only grow when two compounds were synthesized simultaneously: the pigment itself and formic acid, which served as metabolic fuel.

Tricking bacteria into choosing pigment over thrift

Bacteria are efficient — they don't waste energy on nonessential products. The researchers took advantage of that practicality by making pigment production essential to cell growth. Each time a bacterium made one molecule of xanthommatin, it also generated the fuel needed to divide. The result: a feedback loop that pushed cells to prioritize pigment synthesis.

Lead author Leah Bushin described the approach as creating "sick" cells that only recover through continuous pigment production. Senior author Bradley Moore emphasized that this was the first time a team produced xanthommatin in a bacterium at industrially meaningful yields.

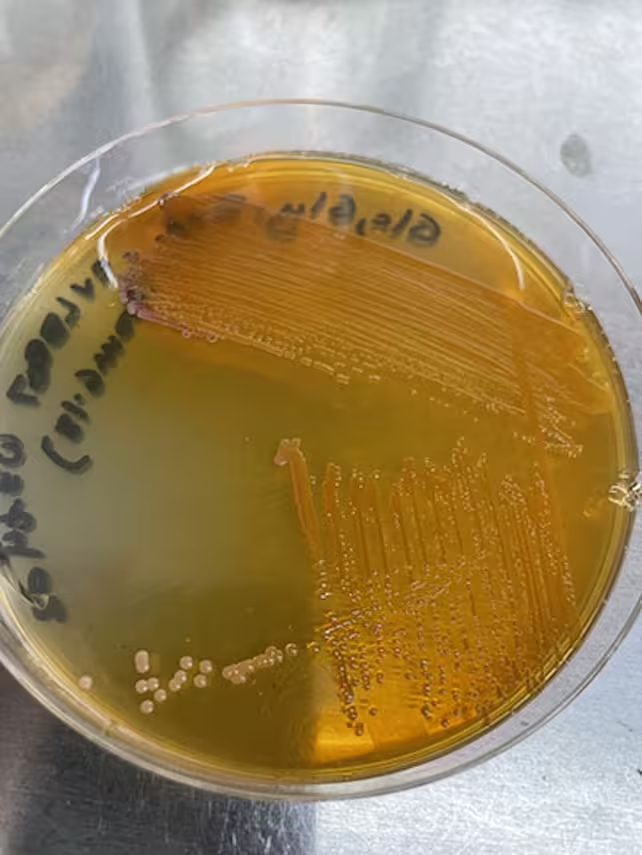

Bacteria producing xanthommatin on a petri dish in the lab

What the team achieved — and why it matters

The engineered strains achieved production levels of up to about 3 grams of pigment per liter of medium — roughly 1,000 times higher than prior methods, which yielded only a few milligrams per liter. While 3 g/L sounds modest compared with bulk commodity chemicals, for a complex natural pigment like xanthommatin this represents a dramatic breakthrough.

Beyond the raw numbers, the study combined several modern tools: adaptive laboratory evolution to let microbes optimize themselves under selective conditions, and bioinformatics to streamline pathways that let the microbes make pigment from a single, simple feedstock such as glucose. Together, these steps reduced the need for multiple nutrient inputs and manual pathway tweaks.

Why chase a cephalopod pigment? For biologists, easier access to xanthommatin will accelerate experiments probing how cephalopods control color at cellular and molecular scales. For engineers and materials scientists, it offers a natural dye with unique optical properties that could inspire adaptive camouflage, responsive coatings or new photonic materials. In a broader sense, the work is a proof of concept: growth-coupled biosynthesis could be adapted to produce other valuable or hard-to-make compounds, improving sustainability in chemical manufacturing.

- Scientific background: Xanthommatin is an ommochrome pigment involved in light absorption and color modulation in many cephalopods.

- Method highlight: Making pigment production essential to growth forces microbes to allocate resources toward the target compound.

- Potential impact: From biological study of camouflage to biomimetic materials and sustainable biosynthesis pipelines.

Expert Insight

Dr. Maya Chen, a synthetic biologist unaffiliated with the study, commented: "This work elegantly merges evolutionary selection with rational engineering. By coupling a desired product to fitness, the researchers sidestep some of the trial-and-error that typically slows strain development. It’s a powerful idea for sustainable biomanufacturing — but translating lab-scale yields to industrial reactors will require further optimization and careful process design."

The team also noted practical considerations: scaling production will involve fermentation engineering, downstream purification, and regulatory review if pigments are used in consumer-facing applications. There are biosecurity and biosafety frameworks to follow, but the pathway — from gene edits to meaningful quantities of pigment — has been demonstrated.

Wider implications and next steps

Think of this result as more than a pigment factory. It demonstrates a way to coax microbes into producing scarce, structurally complex natural products with much higher efficiency than before. If the same growth-coupled logic can be applied to other pathways, manufacturers could produce pharmaceuticals, specialty dyes, or biomaterials with reduced waste and lower carbon footprints.

For cephalopod research, having reliable access to xanthommatin removes a major experimental constraint. Scientists can now run controlled studies on skin optics, test how pigments interact with structural color elements like iridophores, and prototype materials that mimic rapid color change.

Moments of serendipity still fuel discovery: Bushin recalled setting up a culture and returning the next morning to find it abundant with pigment. "It was one of my best days in the lab," she said — a reminder that creative engineering and patient experimentation continue to reveal surprising ways to harness biology.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

atomwave

If they really hit 3 g/L in bacteria that's cool but is it reproducible in big fermenters? sounds like lab luck sometimes.. curious about downstream cleanup

labcore

Whoa that's wild, bacteria forced to make squid pigment? Mind blown. Hope they nail safety and scaling tho, purity, cost.. lots to check. Still, feels huge. quick comment

Leave a Comment