5 Minutes

A newly identified dinosaur named Khankhuuluu — literally “dragon prince” in Mongolian — offers the clearest glimpse yet of how small predators evolved into the bone-crushing Tyrannosaur giants. Unearthed from fossils in Mongolia and described by an international team led by researchers at the University of Calgary, this species rewrites a chapter in tyrannosaur evolution and points to a key migration between Asia and North America.

From museum drawers to a missing link

The fossils that revealed Khankhuuluu had been sitting in collections for decades after initial study in the 1970s by paleontologist Altangerel Perle, who compared them to Alectrosaurus from China. In 2023, Jared Voris, a PhD candidate at the University of Calgary, re-examined specimens at Mongolia’s Institute of Paleontology and spotted distinctive features that separated this animal from previously named species. Working with associate professor Darla Zelenitsky and an international team, Voris published the formal description in Nature.

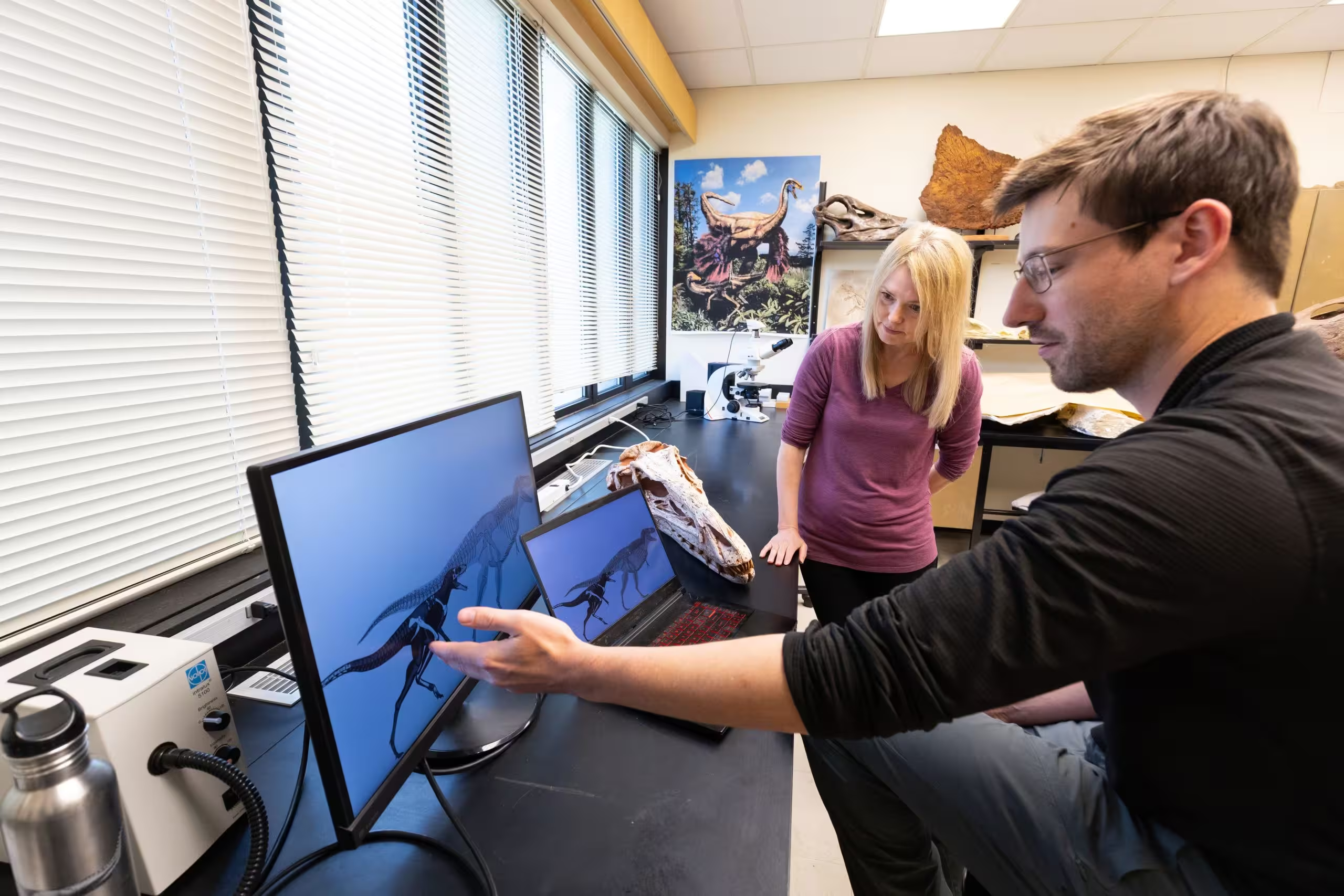

UCalgary paleontologist Darla Zelenitsky and PhD candidate Jared Voris, left, helped identify the dinosaur species using fossils found in Mongolia. Credit: Riley Brandt/University of Calgary

What Khankhuuluu looked like and how it behaved

Khankhuuluu was roughly two to three times smaller than later apex tyrannosaurs such as Tyrannosaurus rex. At about 750 kg — comparable to a modern horse — it combined speed, agility and a lightly built skull, marking it as a mesopredator rather than a bone-crunching scavenger.

Key anatomical traits

- Long, shallow skull: Unlike later tyrannosaurs, Khankhuuluu lacked the robust, deep skull adapted to deliver bone-crushing bites.

- Rudimentary horns: Tiny protuberances on the head suggest the early stages of display or intraspecific signaling that would become more pronounced in relatives like Albertosaurus and Gorgosaurus.

- Slender, athletic body: Limb proportions indicate a fast-running predator that relied on pursuit and agility to subdue prey.

Associate professor Darla Zelenitsky and first author Jared Voris. Credit: Riley Brandt/University of Calgary

Voris describes Khankhuuluu as a transitional form: “This new species provides us the window into the ascent stage of Tyrannosaur evolution; right when they’re transitioning from small predators to their apex predator form.” That transition involved shifts in skull mechanics, body size and feeding ecology over millions of years.

Evolutionary implications: migrations and origins

One of the most significant outcomes of the study is its contribution to the debate over where large tyrannosaurs first evolved. Zelenitsky and colleagues argue that Khankhuuluu, or a close relative, migrated from Asia into North America around 85 million years ago. Once in North America, descendants of that immigrant lineage grew into the continent’s dominant apex predators.

According to the team’s analysis, the fossil record indicates that after this immigration event, Tyrannosaurs were largely restricted to North America for a few million years. Later movements back into Asia set the stage for a split in the family tree: one branch evolved into even larger apex predators culminating in T. rex, while another remained medium-sized with elongated snouts (nicknamed the “Pinocchio rexes”).

“Our study provides solid evidence that large Tyrannosaurs first evolved in North America as a result of this immigration event,” Zelenitsky explains, highlighting how migration and local ecological opportunity combined to produce the group’s remarkable size increase.

Why Khankhuuluu matters to paleontology

Finding a closest-known ancestor in the Asian fossil record fills a long-standing gap in our understanding of tyrannosaur origins. Khankhuuluu is important because it captures an intermediate stage: larger than earlier small-bodied tyrannosauroids but not yet equipped with the extreme cranial strength and bite force of later giants.

Beyond taxonomy, the discovery informs models of faunal exchange between Asia and North America during the Late Cretaceous, the timing of evolutionary innovations like enlarged skulls and reinforced teeth, and the ecological roles early tyrannosaurs occupied as mesopredators before rising to apex status.

Expert Insight

Dr. Elena Márquez, an evolutionary paleobiologist not involved in the study, comments: “Khankhuuluu is a textbook example of how museum collections and fresh fieldwork together reshape evolutionary narratives. It shows us the stepwise nature of adaptation — size, skull form and behavior changing across a lineage as it encounters new environments. This find narrows the gap between small-bodied progenitors and the iconic T. rex.”

Looking forward, researchers aim to trace even earlier ancestors of the apex tyrannosaurs and to refine the timing and pathways of transcontinental migrations. New fieldwork in the Bayanshiree Formation and reexamination of older collections may continue to yield surprises.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

DaNix

Is the migration timeline solid tho? Fossil gaps, sampling bias, could be another explanation... if that's real then huge, but wanna see more specimens

labcore

wow didnt expect a 'dragon prince' to fill that gap, museum drawers still full of surprises. who knew migration played such a big role? wild.

Leave a Comment