5 Minutes

New research indicates that a surprisingly large number of people who recovered from COVID-19 may now be living with reduced or absent smell — and many don’t even know it. Objective tests reveal lingering olfactory deficits that patients often underestimate, a finding with public-health and quality-of-life implications.

Large study finds hidden smell loss after COVID-19

Scientists in the United States evaluated nearly 3,600 adults to measure long-term changes in smell after SARS-CoV-2 infection. The team ran standardized smell tests on 2,956 volunteers with a confirmed history of COVID-19 and 569 people who reported never having had the virus. On average, testing occurred around 671 days — nearly two years — after participants’ first COVID-19 test.

The results were striking. Among the COVID-19 group, 1,393 participants reported noticing smell problems; objective testing confirmed impairment in roughly 80% of those cases. But perhaps more alarming: of the 1,563 people in that same group who said their smell seemed normal, two-thirds (about 66%) actually had measurable hyposmia (reduced smell) or anosmia (loss of smell) when tested.

“Our findings confirm that those with a history of COVID-19 may be especially at risk for a weakened sense of smell, an issue that is already underrecognized among the general population,” says Dr. Leora Horwitz of the New York University Grossman School of Medicine, a co-author on the published paper.

Why many people don’t notice smell loss

The study also tested the control group — people who reported no COVID-19 history — and found that about 60% showed some smell deficiency. That number is higher than expected and likely reflects both underreporting and undetected infections. The researchers note that infections can damage sensory cells and neural pathways in the nose, and some people may simply adapt to a dulled aroma world without realizing it.

Smell is more than a luxury

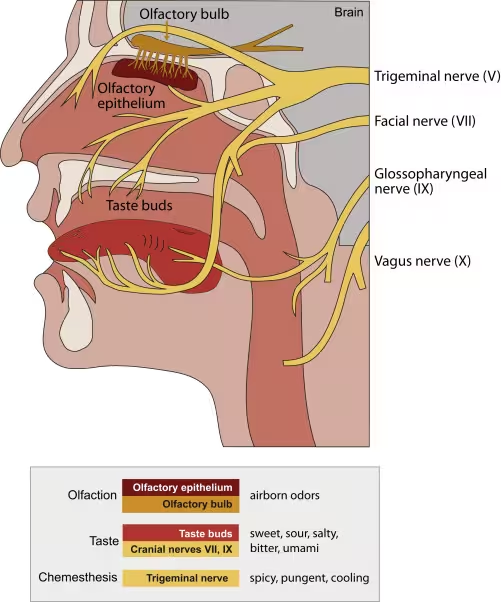

Smell plays important roles beyond pleasure and memory. It warns of hazards such as gas leaks, spoiled food and smoke, and it’s closely linked to taste and appetite. Loss of smell has also been associated with cognitive decline in other contexts, like Alzheimer’s disease, which raises questions about overlapping mechanisms and long-term brain health after viral infections.

COVID-19’s effect on smell was one of the most visible early symptoms of the pandemic, but most attention focused on acute anosmia. This study shifts the spotlight to persistent, often-unrecognized olfactory deficits that can last months or years and that patients may underestimate.

Study methods and real-world implications

The researchers used validated olfactory tests rather than self-report alone, which is key: previous surveys suggested links between COVID-19 and smell loss, but objective testing provides stronger evidence. The team points out that extrapolating from sample to global population has limits, yet if these patterns hold more broadly, millions could be living with reduced smell without knowing it.

That has practical consequences. A dulled sense of smell affects nutrition, safety and mental well-being. People who can’t detect odors may eat less or lose interest in food, and they might miss environmental warning signs. The authors recommend integrating smell testing into post-COVID care and developing interventions to restore olfactory function where possible.

Smell receptors and taste buds in the nose and mouth. Chemesthesis is the detection of chemical compounds by pain-sensing and touch neurons.

What the research adds to the big picture

This paper, published in JAMA Network Open, corroborates earlier small-scale studies and survey data that suggested underappreciated long-term olfactory dysfunction after SARS-CoV-2 infection. It also highlights a diagnostic gap: many patients underestimate their own smell loss, so routine screening would identify problems that otherwise go unnoticed.

The causes of unrecognized smell loss remain uncertain. Damage to peripheral olfactory receptors, inflammation in nasal tissue, or changes in central brain processing could all play a role. The study authors also raise the possibility that COVID-19-related brain changes might blunt people’s subjective awareness of sensory loss.

Expert Insight

“Objective testing is a wake-up call,” says Dr. Ana Morales, a clinical neurologist and sensory researcher. “Smell is a sentinel sense — it informs safety, nutrition and emotional memory. If millions have reduced smell after COVID-19, we need screening programs and accessible rehabilitation, such as olfactory training, plus more study of the neural mechanisms so therapies can be targeted.”

Practical next steps include wider adoption of simple smell tests in primary care, longitudinal studies tracking recovery trajectories, and trials of interventions that might restore smell after viral damage. For individuals, paying attention to changes in appetite, food enjoyment and awareness of household hazards can be an important first line of defense.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

Tomas

I lost my smell after Covid, took months to notice. Food tasted blah, still paranoid about gas leaks. Olfactory training helped a bit, not a miracle tho

labcore

Wait, 66% who said their smell was fine actually had loss? Is the test that sensitive or are there confounders?? if that's real then...

Leave a Comment