5 Minutes

Forty years after Voyager 2's historic flyby, researchers at the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) propose a compelling explanation for the spacecraft’s puzzling radiation measurements at Uranus: a powerful solar wind disturbance may have boosted the planet’s electron belts to extreme levels.

Scientists now think a major solar wind event supercharged Uranus’ radiation belts during Voyager 2’s flyby, offering a new explanation for puzzling decades-old measurements. Credit: Shutterstock Powerful waves unleashed by solar storms could be the key to understanding extreme radiation.

A decades-old puzzle: what Voyager 2 actually saw

When Voyager 2 swept past Uranus in January 1986 it recorded unexpectedly intense electron radiation trapped within the planet’s magnetosphere. The measured energies were far higher than models and comparisons with other planets predicted. At the time, researchers assumed Uranus’ unusual tilt and magnetospheric geometry made the readings anomalous — but there was no convincing mechanism to produce such sustained high-energy populations.

Voyager 2 remains the only spacecraft to visit Uranus, so that single dataset has framed our understanding of the planet’s space environment for decades. The anomaly raised practical and theoretical questions: how do Uranus’ unique magnetic geometry and occasional solar wind disturbances interact, and could transient space weather create brief but extreme radiation conditions?

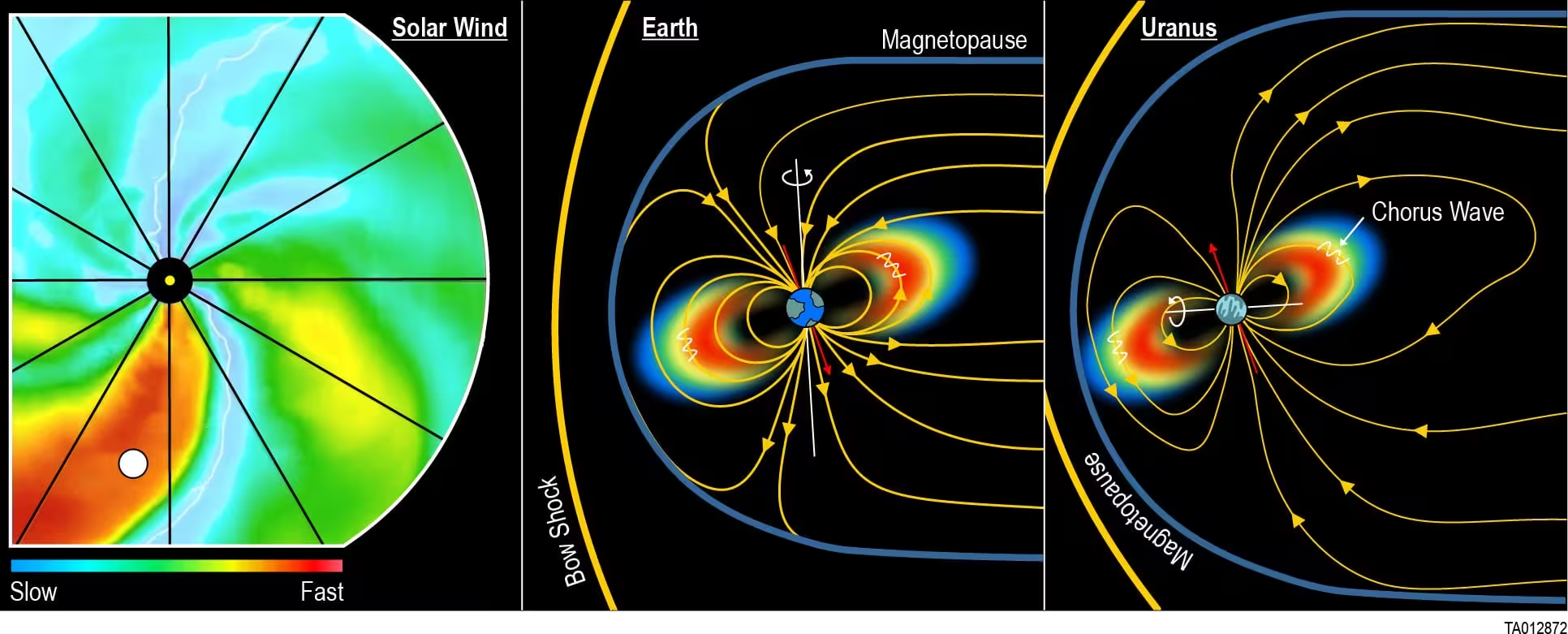

SwRI scientists compared space weather impacts of a fast solar wind structure (first panel) driving an intense solar storm at Earth in 2019 (second panel) with conditions observed at Uranus by Voyager 2 in 1986 (third panel) to potentially solve a 39-year-old mystery about the extreme radiation belts found. The ‘chorus’ wave is a type of electromagnetic emission that may accelerate electrons and could have resulted from the solar storm. Credit: Southwest Research Institute

How a solar wind feature could have powered Uranus’ belts

The new analysis centers on a structure called a co-rotating interaction region (CIR) — a boundary in the solar wind where fast and slow plasma streams collide, compressing magnetic fields and driving intense wave activity. At Earth, CIRs and related disturbances can trigger 'chorus' electromagnetic emissions that efficiently accelerate trapped electrons to higher energies.

Dr. Robert Allen of SwRI, lead author on the study, says the team used a comparative approach: ‘‘Science has come a long way since the Voyager 2 flyby. We decided to take a comparative approach looking at the Voyager 2 data and compare it to Earth observations we’ve made in the decades since.’’ Their findings show that the signature Voyager recorded at Uranus resembles conditions produced when a CIR or other fast solar wind structure passes through a magnetosphere, producing high-frequency waves that both scatter and, under certain circumstances, accelerate electrons.

SwRI co-author Dr. Sarah Vines adds context from a recent terrestrial example: ‘‘In 2019, Earth experienced one of these events, which caused an immense amount of radiation belt electron acceleration. If a similar mechanism interacted with the Uranian system, it would explain why Voyager 2 saw all this unexpected additional energy.’’

Why chorus waves matter and how particles gain energy

Chorus waves are a type of plasma emission observed in many planetary magnetospheres. They arise when energetic electrons interact with magnetic field inhomogeneities and can transfer energy to other electrons via resonant wave–particle interactions. Depending on wave amplitude, frequency and background plasma conditions, these emissions either scatter particles into the atmosphere or accelerate them into higher-energy populations that strengthen radiation belts.

At Uranus, where the magnetic axis is dramatically tilted and offset, the geometry of wave generation and particle trapping is complex. A transient but intense driver such as a CIR could create the right combination of wave power and timing to momentarily boost electron energies — producing the extreme readings Voyager 2 recorded.

Implications for future missions and icy-giant science

These results are more than historical clarification. If brief space weather events can dramatically alter a planet’s radiation environment, mission planners need to account for episodic hazards when designing spacecraft electronics, radiation shielding and measurement campaigns for Uranus or Neptune.

‘‘This is just one more reason to send a mission targeting Uranus,’’ Allen said. ‘‘The findings have some important implications for similar systems, such as Neptune’s.’’ Better in situ measurements would reveal whether the Voyager snapshot captured a rare spike or a recurring phenomenon in the outer solar system.

Expert Insight

Dr. Elena Morales, a planetary space physicist unaffiliated with the study, notes: "Comparative magnetospheric science is powerful. By studying analogous events at Earth we can decode sparse measurements from distant flybys. This work shows how important it is to pair historical data with modern space weather theory — especially before we design instruments for future Uranus missions."

Understanding transient drivers like CIRs, chorus wave generation, and their role in particle acceleration sharpen models of planetary magnetospheres and improve predictions of radiation hazards across the solar system. For now, Voyager 2’s surprising readings are less a mystery than a prompt: outer-planet space weather is dynamic, and our best answers will come from new missions equipped to watch those dynamics in real time.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

Tomas

Is this even true? Voyager was a one-off, solar wind spikes sound plausible but we need more data tho, one flyby isnt enough...

astroset

wow didnt expect Voyager readings to be explained like this, chorus waves?? kinda poetic, but also makes sense, if true insane radiation spike

Leave a Comment