6 Minutes

New genetic detective work suggests the first steps toward complex, nucleated cells—ancestors of everything from amoebas to humans—began almost 3 billion years ago. That timing pushes back the origins of eukaryotic complexity by up to a billion years and implies a gradual evolutionary buildup that long preceded Earth’s oxygenation.

Rethinking when complexity began

Life on Earth is often sorted into two broad camps: prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea) and eukaryotes (cells with nuclei and organelles). Prokaryotes appeared first, roughly 4 billion years ago, as compact, efficient cells with free-floating DNA and minimal internal structure. Eukaryotes, by contrast, possess internal membranes, a nucleus, and organelles such as mitochondria that support larger, more regulated genomes and cellular functions.

But exactly when and how that leap toward cellular complexity occurred has been debated. A key uncertainty has been the timing of the mitochondrial takeover—the ancient partnership in which a free-living bacterium became the cell’s energy factory. Did mitochondria trigger the rise of eukaryotic features, or did proto-eukaryotes develop complexity first and then acquire mitochondria?

How a molecular clock rewrites the timeline

To address this, a team led by paleobiologist Christopher Kay (University of Bristol) applied a broad molecular clock analysis across hundreds of species. Molecular clocks estimate divergence times by comparing DNA or protein sequences and applying mutation rates calibrated with fossil constraints. The project combined phylogenetics, paleontology and molecular biology to place the emergence of specific gene families on an absolute timeline.

The team's timeline of the evolution of eukaryotes

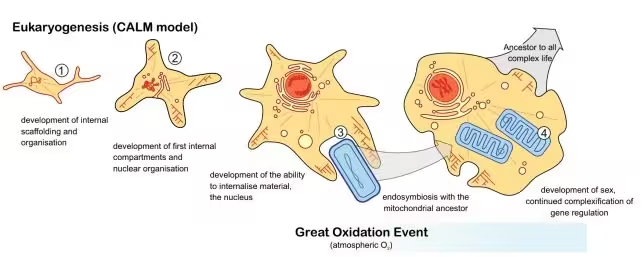

The researchers developed a model called CALM—Complex Archaeon, Late Mitochondrion—to map when eukaryotic traits first appeared. Rather than relying on a few marker genes, they traced hundreds of gene families that underlie hallmark eukaryotic structures and processes.

Key findings: early scaffolding, late mitochondria

The results are striking. Signatures for proteins involved in building a cytoskeleton—actin and tubulin—along with rudimentary cytoskeletal structures and an incipient protonucleus appear around 2.9 to 3.0 billion years ago. Subsequent waves of innovation included evolution of internal membranes, components related to the Golgi apparatus, and expanded systems for gene expression such as diverse RNA polymerases.

In contrast, the lineage leading to mitochondria is dated significantly later, at roughly 2.2 billion years ago. That timing aligns closely with the Great Oxidation Event, when atmospheric oxygen rose sharply. The implication: many eukaryotic innovations were already underway in low-oxygen conditions, but the arrival of mitochondria and changing redox conditions likely accelerated diversification and complexity.

Why this matters for evolutionary biology

If early eukaryotic traits emerged billions of years before mitochondria, it suggests a drawn-out sequence of innovations rather than a single, dramatic leap. Simple cytoskeletal systems and compartmentalizing membranes would have provided organizational advantages—improved genome management, intracellular transport, and spatial regulation—even in an anoxic world.

Then, when oxygen levels rose and mitochondria were incorporated, cells could harness more efficient energy metabolism (ATP production) and expand energy-intensive processes, facilitating larger genomes, increased cellular complexity, and new ecological roles.

Methodological depth and interdisciplinary work

What distinguishes this study is its gene-level resolution tied to absolute time. By analyzing protein interactions, functionally grouping gene families, and anchoring molecular rates with fossil evidence, the authors reconstructed not just a divergence tree but the sequential emergence of cellular systems. This required cross-disciplinary expertise—paleontology to provide age constraints, phylogenetics to build robust trees, and molecular biology to interpret gene function.

As the lead investigators note, such an approach makes it possible to ask precise evolutionary questions: which molecular modules arose first, which were co-opted later, and how environmental shifts influenced biological innovation.

Implications and future directions

These findings recalibrate our view of the deep history of life. They suggest that complex cellular organization evolved slowly under low-oxygen conditions and then expanded rapidly when energy availability increased. That has implications for how we search for complex life elsewhere: life can assemble complexity in stages, perhaps long before planetary oxygenation.

Future research will refine timing estimates, test the CALM model against additional genomes, and explore how environmental variables—nutrients, redox states, and microbial ecology—shaped early eukaryotic evolution. Ancient rock records, novel biomarkers, and increasingly complete genomes from diverse microbial lineages will all contribute to a finer-grained picture.

Expert Insight

"These results paint a picture of incremental innovation rather than an overnight transformation," says Dr. Elaine Moreno, an evolutionary biologist not involved in the study. "Seeing cytoskeletal components and membrane systems appear so early suggests natural selection was experimenting with internal cellular architecture long before mitochondria showed up. When oxygenation and mitochondrial endosymbiosis occurred, those pre-adapted systems could scale up quickly."

"From a practical standpoint, this work underscores the value of integrating fossils, functionally informed gene trees, and broad taxonomic sampling. It’s a powerful template for studying deep evolutionary transitions," she adds.

What to watch next

- Expanded genomic sampling of archaea and deep-branching eukaryotes to test the ubiquity of early eukaryotic markers.

- Geochemical studies refining the timing and regional variability of oxygen increases on early Earth.

- Experimental work on ancestral protein reconstructions to evaluate how primitive cytoskeletal elements functioned in low-oxygen environments.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

coinpilot

Wait, how reliable are these molecular clocks? Fossil calibrations can be messy, so is 3.0 Ga solid or a stretch... idk, curious.

bioNix

Whoa, 3 billion years? mind blown. If cytoskeleton came that early, life was tinkering for ages, wild..

Leave a Comment