7 Minutes

This year’s Antarctic ozone hole was unexpectedly small and short-lived, according to NOAA and NASA analyses. Scientists point to falling chlorine levels in the stratosphere and a weaker polar vortex as the primary drivers behind a significantly reduced ozone loss during the 2025 Southern Hemisphere spring.

A surprisingly small ozone hole in 2025

During its peak season from September 7 through October 13, 2025, the Antarctic ozone hole averaged about 7.23 million square miles (18.71 million square kilometers). Its largest single-day extent came on September 9, when the depleted region reached 8.83 million square miles (22.86 million square kilometers). That single-day peak is roughly 30% smaller than the largest ozone hole on record (2006), which averaged 10.27 million square miles (26.60 million square kilometers).

Relative to long-term records stretching back to the satellite era (1979), the 2025 hole ranks among the smaller events: it is the fifth smallest since systematic records began in 1992 and the 14th smallest in the 1979–2025 satellite record. Perhaps more striking, the hole began to break apart nearly three weeks earlier than the typical timing observed over the past decade.

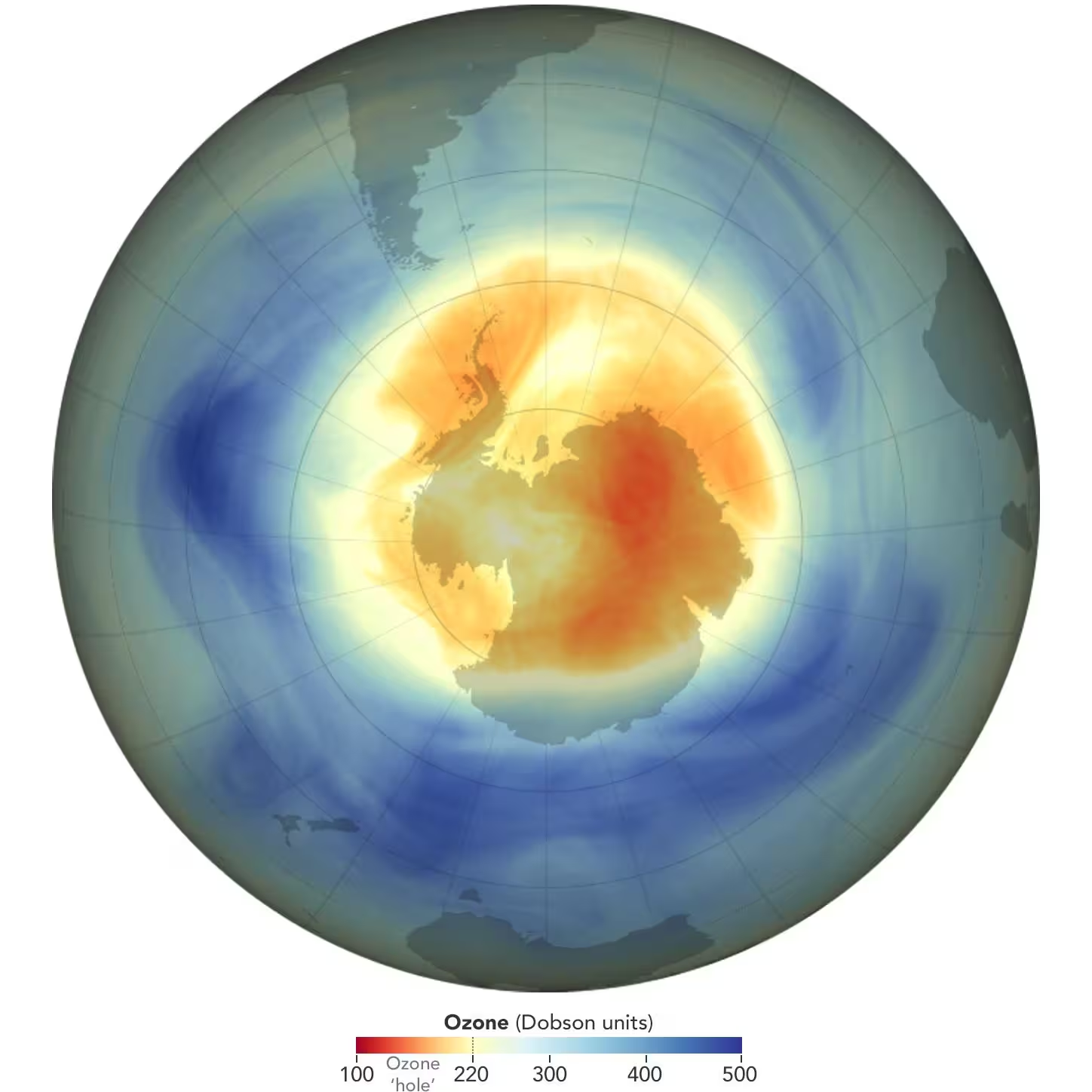

This illustration shows the size and shape of the ozone hole over the South Pole on the day of its 2025 maximum extent. Moderate ozone losses (in orange) are visible amid areas of more potent ozone losses (in red). Scientists describe the ozone “hole” as the area in which ozone concentrations drop below the historical threshold of 220 Dobson Units. Credit: NASA Earth Observatory image by Lauren Dauphin created with data courtesy of NASA Ozone Watch and GEOS-5 data from the Global Modeling and Assimilation Office. Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

How scientists measured the 2025 ozone dip

Tracking the ozone layer requires multiple, complementary instruments. Satellites — including NASA’s Aura, NOAA-20 and NOAA-21, and the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership — provide broad, continuous views of stratospheric ozone. On the ground and in situ, NOAA teams launch weather balloons fitted with ozonesondes that directly sample ozone concentrations from the surface into the stratosphere.

Overwintering NOAA technicians prepare to launch a weather balloon carrying an ozonesonde. This instrument measured the annual formation of the Antarctic Ozone Hole over the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station on September 15, 2025. Credit: Dr. Simeon Bash (University of Chicago/South Pole Telescope)

Balloon profiles and satellite retrievals reported a minimum local value of 147 Dobson Units directly above the South Pole on October 6, 2025. To put that in context, the most depleted air measured there ever reached 92 Dobson Units in October 2006. Scientists define the ozone "hole" as regions where column ozone drops below about 220 Dobson Units; the lower the number, the more UV radiation can penetrate to the surface.

Why the 2025 hole was smaller: chemistry and circulation

Two factors combined this season to limit ozone loss: a long-term decline in chlorine- and bromine-bearing chemicals in the stratosphere, and a naturally weaker polar vortex during austral winter and early spring. The polar vortex is a ring of low-temperature, high-speed winds encircling Antarctica; when it is strong and cold, conditions favor chemical reactions on polar stratospheric clouds that release reactive chlorine and bromine and accelerate ozone destruction.

“As predicted, we’re seeing ozone holes trending smaller in area than they were in the early 2000s,” said Paul Newman, senior scientist and longtime leader of NASA’s ozone research efforts. Observations show that levels of many ozone-depleting substances have been steadily declining since they peaked around 2000.

NOAA senior scientist Stephen Montzka notes that, relative to the era of the largest ozone holes, chlorine abundances in the Antarctic stratosphere have fallen substantially. "Since peaking around the year 2000, levels of ozone-depleting substances in the Antarctic stratosphere have declined by about a third relative to pre-ozone-hole levels," Montzka said. NASA researchers estimate that, had stratospheric chlorine remained at levels seen 25 years ago, the 2025 ozone hole would have been more than one million square miles larger.

Legacy emissions and the long road to recovery

Despite the clear recovery signal, the ozone layer will not rebound overnight. Many ozone-depleting chemicals — notably chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and halons — are long-lived and remain trapped in older products, building insulation, and landfill materials. Those legacy sources continue to release small amounts of chlorine and bromine that slowly decay over decades.

Scientists project that, if current policies remain in place and emissions from legacy sources continue to decline, the Antarctic ozone hole will steadily shrink and likely return to near pre-1980 conditions by the late 2060s. Natural variability — particularly changes in stratospheric temperatures and the strength of the polar vortex — means that some years will be better or worse than the trend line, but the overall trajectory is toward recovery.

Public health and ecological stakes

The ozone layer is Earth’s built-in shield against harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation. As stratospheric ozone declines, more UV-B radiation reaches the surface, increasing risks for skin cancer, cataracts, and damage to crops and marine ecosystems. The improvements documented in 2025 therefore carry real public-health and environmental benefits, but they do not eliminate the need for ongoing prevention and monitoring.

American scientific and policy leadership has played a central role in identifying the problem and driving solutions. The Montreal Protocol — the 1987 international treaty phasing out ozone-depleting substances and later strengthened by amendments — remains the most important single policy success behind the ozone layer’s recovery to date.

Monitoring the future: satellites, balloons and models

Maintaining and improving the satellite fleet and ground-based networks that monitor stratospheric composition will be critical. Continued observations from NOAA and NASA platforms, in combination with global modelling efforts, help researchers separate the effects of chemistry and dynamics, identify unexpected emissions, and fine-tune recovery timelines.

Scientists also emphasize the value of public communication: explaining what Dobson Units measure, why the polar vortex matters, and how international policy connects to tangible improvements in atmospheric health helps sustain public and political will for long-term environmental stewardship.

Expert Insight

“The 2025 season gives us a clear, encouraging datapoint,” said Dr. Elena Morales, an atmospheric chemist at the University of Colorado Boulder. “It demonstrates how effective international policy, combined with relentless observation, can change the chemistry of the atmosphere in measurable ways. That said, the path to full recovery is decades long — we must keep monitoring, and remain vigilant about legacy sources and new chemicals that could cause setbacks.”

As the atmosphere slowly heals, each season’s measurements — whether showing large holes or small ones like in 2025 — become a critical chapter in an international success story that links science, policy and public health.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

Marius

So smaller hole cuz vortex was weak and chlorine fell? ok but how certain are the satellite/balloon numbers... natural variability can trick stats, no?

astroset

wow didnt expect such a small ozone hole! real proof policies work, but legacy CFCs still leaking, decades to go. bittersweet.

Leave a Comment