8 Minutes

Why headline TPS often misrepresents real scalability

Blockchain transactions per second (TPS) is widely used as a shorthand for performance, but headline TPS figures rarely reflect what a live, decentralized network can sustain. High TPS numbers are attractive in white papers and marketing decks, yet every extra transaction increases the computational and network burden on the nodes that keep a ledger decentralized. That tension — between raw execution speed and the cost of decentralization — explains why theoretical TPS often collapses once a chain runs in production.

Benchmarks vs. production networks

Many early benchmarks or pre-mainnet tests measure TPS under idealized conditions: a single node or a tightly controlled testnet. Those conditions measure virtual machine speed or isolated execution throughput rather than full network scalability. Carter Feldman, founder of Psy Protocol and a former hacker and block producer, notes that single-node measurements are misleading because they omit the costs of relaying and verifying transactions across a distributed topology.

"Many pre-mainnet, testnet or isolated benchmarking tests measure TPS with only one node running. At that point, you might as well call Instagram a blockchain that can hit 1 billion TPS because it has one central authority validating every API call," Feldman has said.

Execution is only one piece of the puzzle

A blockchain's performance profile includes multiple layers: how fast the virtual machine executes transactions, how nodes communicate (bandwidth and latency), and how leaders and validators relay and confirm data. Benchmarks that separate execution from relay and verification measure something closer to VM throughput than network scalability. In practice, the network must ensure that every full node can verify transactions and that invalid data is rejected — the very feature that guarantees decentralization.

New projects advertise high TPS, though live network usage rarely approaches those ceilings.

Historical examples: EOS and Solana

EOS published a theoretical TPS ceiling in the millions, yet it never achieved that level on mainnet. Whitepaper claims of up to ~1 million TPS were eye-catching, but realistic tests and research painted a different picture. Whiteblock testing and other real-world analyses showed throughput falling to roughly 50 TPS under practical network conditions.

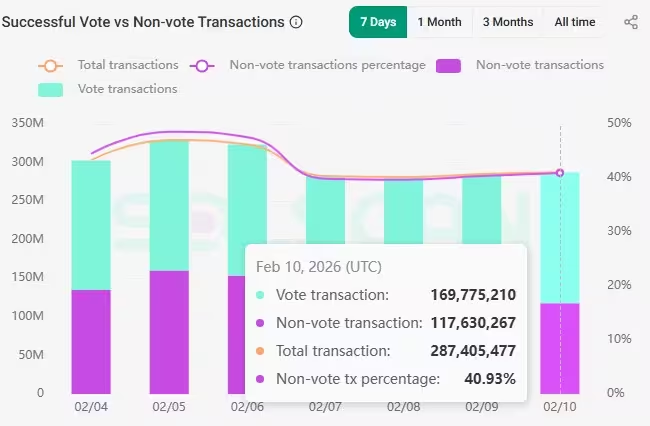

More recently, Jump Crypto’s Firedancer validator client demonstrated 1 million TPS in controlled tests. That achievement validates how far engineering can push execution speed. However, the Solana network in live conditions typically processes on the order of 3,000–4,000 TPS; a material share of that figure is consumed by vote or consensus traffic rather than pure user transactions. Around 40% of on-chain activity in Solana’s totals can be non-user or non-vote traffic, so actual user-facing throughput is lower.

Solana recorded 1,361 TPS without vote transactions on Feb. 10.

These examples illustrate a consistent pattern: isolated performance records are not the same as sustainable mainnet throughput where decentralization, network propagation, and verification costs are all in play.

The linear scaling problem and decentralization costs

Throughput typically scales linearly with workload: twice as many transactions equals roughly twice the work. That linear relationship becomes a problem because each node must receive and verify a growing volume of data. Bandwidth caps, CPU limits, storage I/O, and synchronization delays eventually form hard bottlenecks. As you push TPS higher without changing the verification model, the set of machines able to run a full node shrinks, concentrating validation power and eroding decentralization.

That trade-off is fundamental in many existing blockchain architectures: raw TPS gains come at the expense of the diversity and geographical distribution of validators. Project teams often mitigate the pressure by increasing hardware requirements, but this shifts the network toward a smaller, more professionalized validator set.

Separation of execution and verification

One way to reduce per-node burden is to separate execution from verification. Instead of every node executing every transaction, nodes verify a compact proof that the transactions were processed correctly. That approach lowers verification costs for ordinary nodes while concentrating intense work on specialized provers.

Feldman highlights zero-knowledge (ZK) proofs as a key tool for this design. Zero-knowledge cryptography lets a prover convince verifiers that a batch of transactions was executed correctly without revealing all intermediate data or requiring every node to replay every transaction. This reduces the verification load that each full node must bear.

Recursive ZK-proofs and proof aggregation

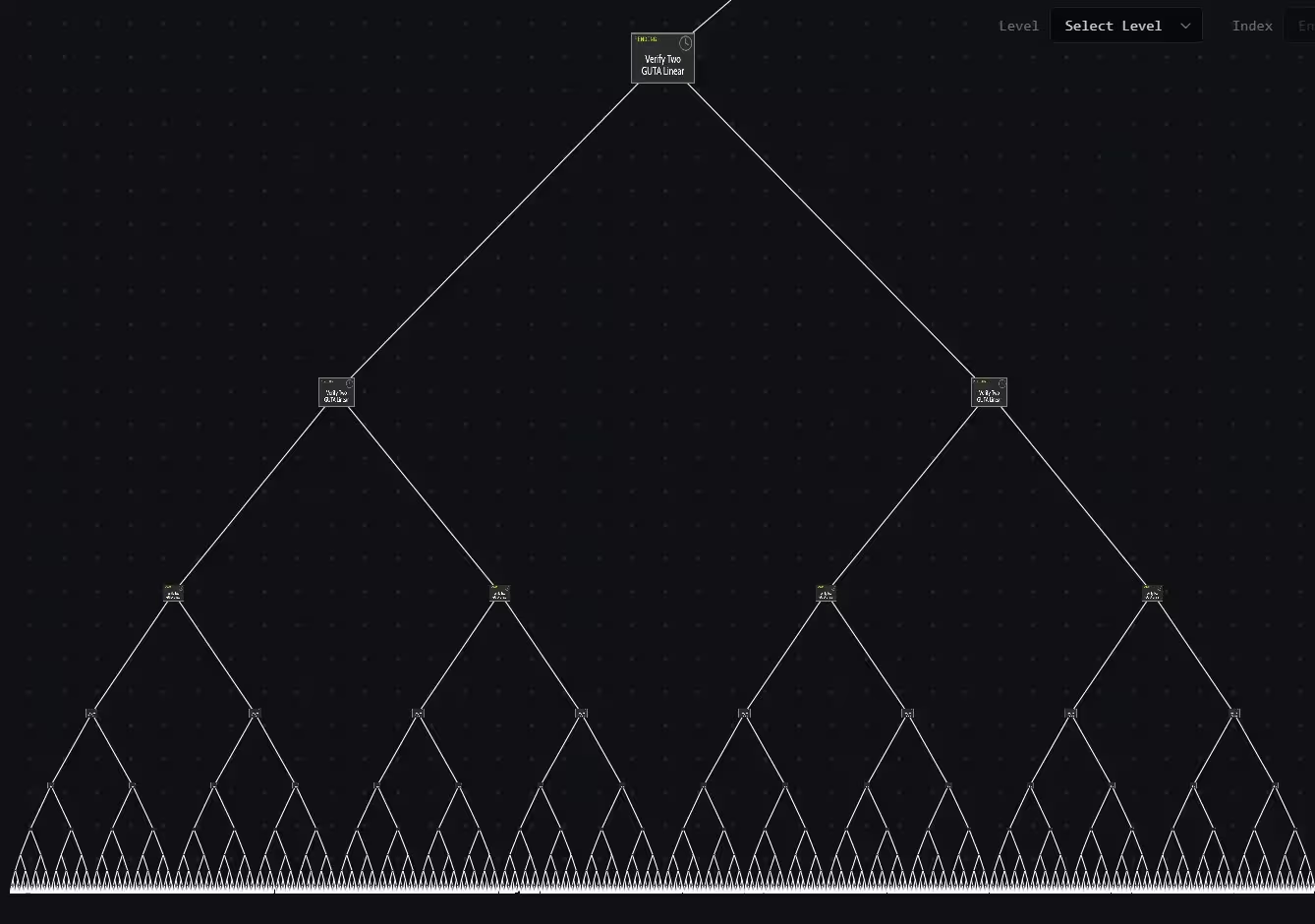

Recursive ZK-proofs let multiple proofs be combined into a single proof that attests to the correctness of many prior proofs. Feldman illustrated this with a proof tree: 16 user transactions can become eight proofs, which in turn compress into four proofs, then two, and eventually one compact proof. The end result is a single, small artifact that proves the correctness of a large batch of transactions.

How several proofs become one.

Using recursive proofs, throughput can increase without a proportional rise in per-node verification costs. That means higher effective TPS at the network level while keeping validation cheap for ordinary nodes. However, the cost doesn't disappear — it shifts. Generating ZK proofs can be computationally expensive and typically requires specialized hardware or infrastructure. The heavy lifting is moved to provers, which can be centralized if not carefully designed, again creating trade-offs with decentralization.

Why most chains still use traditional models

Adopting proof-based verification often means redesigning core components of a blockchain: state representation, execution models, and how data availability is handled. Retrofitting ZK-based validation into a conventional EVM or sequential execution model is complex. That explains why many established networks continue to rely on traditional execution and verification despite the theoretical benefits of ZK approaches.

Feldman also noted historical funding dynamics: early investors and teams favored projects that matched familiar execution models (like EVM-compatible chains). Building a ZK-native execution stack required more time and novel engineering, which initially made fundraising harder for some teams.

Performance metrics beyond raw TPS

TPS is a useful metric when used correctly — measured in production and including relay and verification costs — but it is not the only indicator of network health. Economic metrics such as transaction fees, fee market behavior, and average transaction finality offer clearer signals of demand and capacity. A blockchain with low fees despite high on-paper TPS may indicate underused capacity, while rising fees at modest TPS can signal congestion and real-world limits.

"I would contend that TPS is the number two benchmark of a blockchain’s performance, but only if it is measured in a production environment or in an environment where transactions are not just processed but also relayed and verified by other nodes," Feldman has emphasized.

LayerZero Labs and others have claimed dramatic TPS ceilings by combining execution innovations with ZK primitives. For example, LayerZero promoted a Zero chain claiming it can scale to millions of TPS by leveraging ZK tech. These approaches are promising, but their long-term decentralized viability depends on how proof generation and validation are distributed across the network.

Practical takeaways for developers and users

- Read TPS claims critically: ask how tests were run and whether relay, bandwidth, and verification costs were included.

- Favor production benchmarks: mainnet measurements under normal user load are more telling than pre-mainnet demos.

- Watch economic signals: transaction fees and mempool behavior provide practical evidence of network limits.

- Assess decentralization impact: higher TPS is valuable, but not if it concentrates validation or requires prohibitive hardware.

- Track advancements in ZK tooling: recursive proofs and proof aggregation can break the linear trade-off, but they introduce their own architectural and economic trade-offs.

Conclusion

Headline TPS numbers are attractive but incomplete. Real-world scalability must account for how transactions are broadcast, verified, and economically incentivized across a decentralized network. Techniques such as separating execution from verification and using zero-knowledge proofs — especially recursive ZK — offer promising paths to higher usable throughput. Still, these solutions shift burdens rather than eliminate them, and they require careful engineering to preserve decentralization. For now, the best metric for gauging a chain’s ability to scale remains production-tested throughput paired with economic indicators like fees and validator distribution.

Source: cointelegraph

Comments

Kaden

is this even true? single-node tests are basically dishonest, but how do you trust proof generation isn't centralized? curious..

bitvector

wow i always thought TPS was just hype, nice breakdown. but ZK sounds like magic, who pays for those heavy provers? feels like centralization risk...

Leave a Comment