6 Minutes

When Ford Tried to Remove the Crankshaft

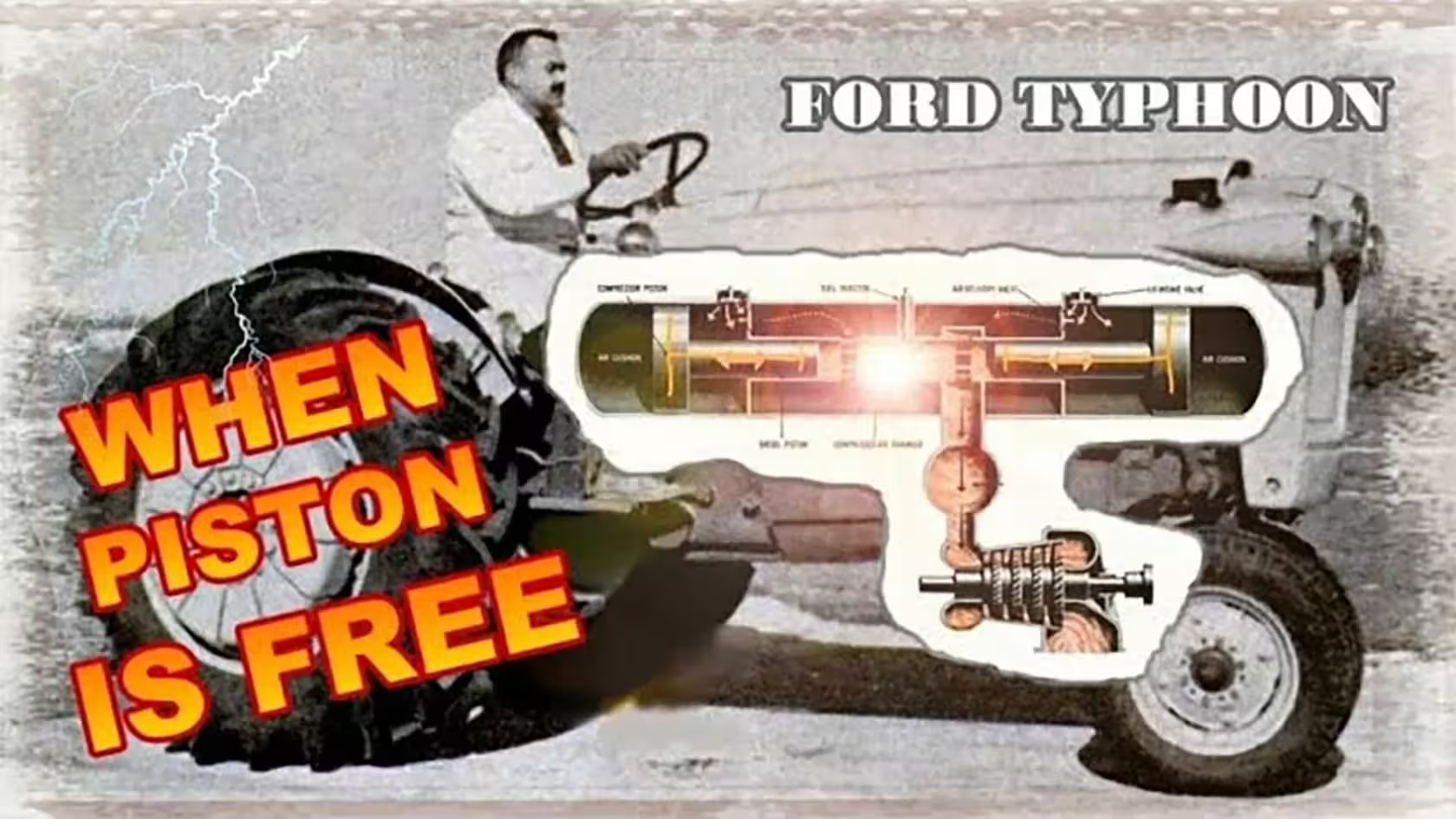

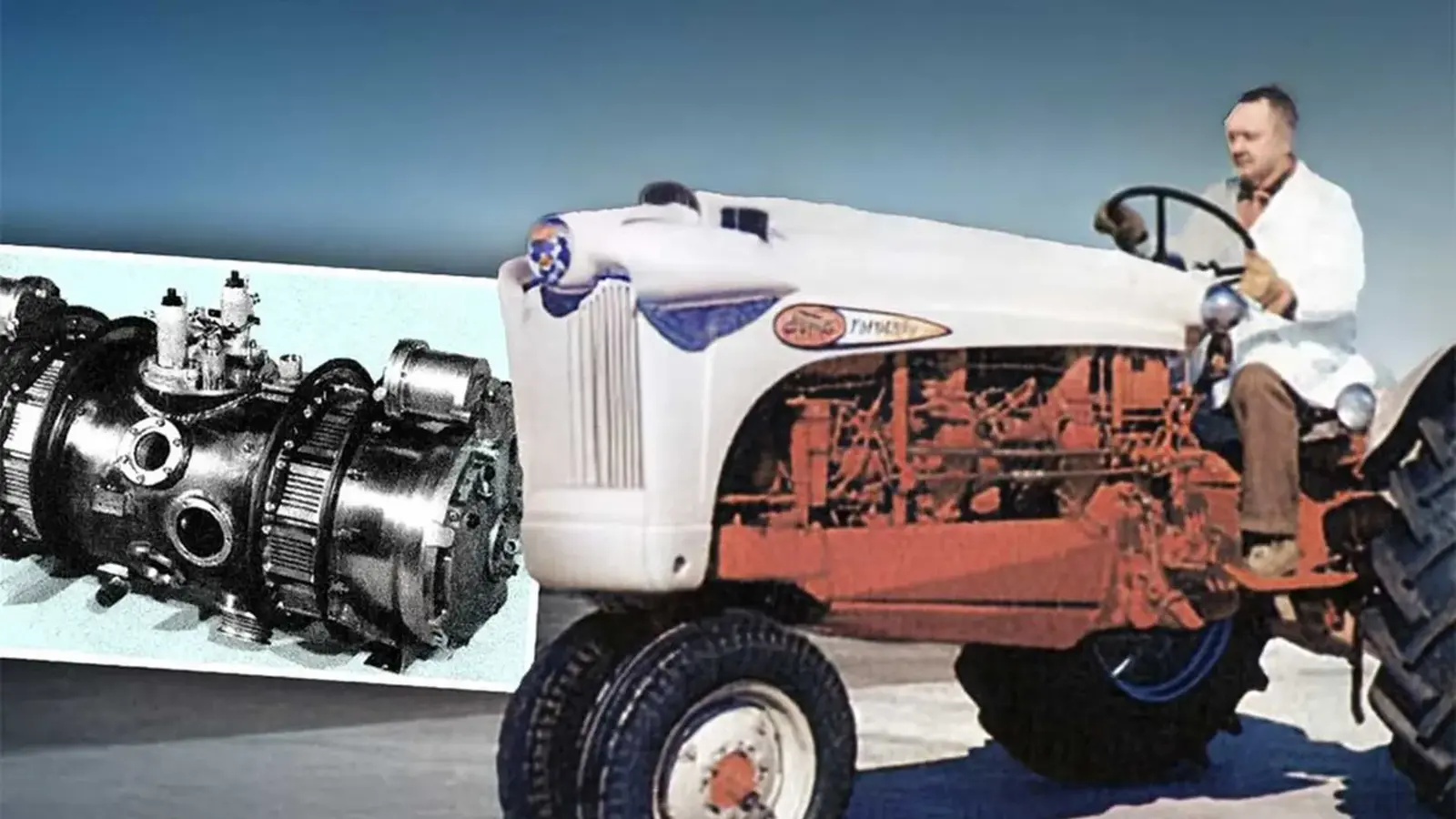

Forget everything you know about internal-combustion engines. In the 1950s Ford built an engine with no crankshaft and no camshaft — a machine that looked nothing like conventional powerplants and was installed in a tractor called the Typhoon. Branded at the time as a possible “engine of tomorrow,” this free-piston design promised fewer moving parts, lower cost, and the ability to run on many fuels.

From a Cold Shed to a Public Reveal

The story doesn’t start in an ultra-modern R&D center. In 1954 an engineer named Paul Klotsch (working with three assistants) pressed his idea on Ford management and was initially dismissed. Undeterred, he and his small team retreated to an unheated shed on Ford’s grounds and built a crude 10-horsepower prototype in freezing conditions. That humble demonstrator convinced executives the idea deserved funding.

By March 1957 Ford publicly revealed the Typhoon tractor, and under its hood was an engine that defied expectations: one cylinder, two opposing pistons — and a gas turbine driven by combustion gases rather than a crankshaft-driven flywheel.

How the Free-Piston, Crankless Engine Worked

Design and basic operation

At its heart the engine resembled a dumbbell. A single horizontal cylinder housed two pistons that moved toward and away from each other. The cycle began with compressed air pushing the pistons together. Fuel was injected into the intensely hot air between them, producing a powerful combustion event that drove the pistons outward. There was no crank to convert linear motion to rotation.

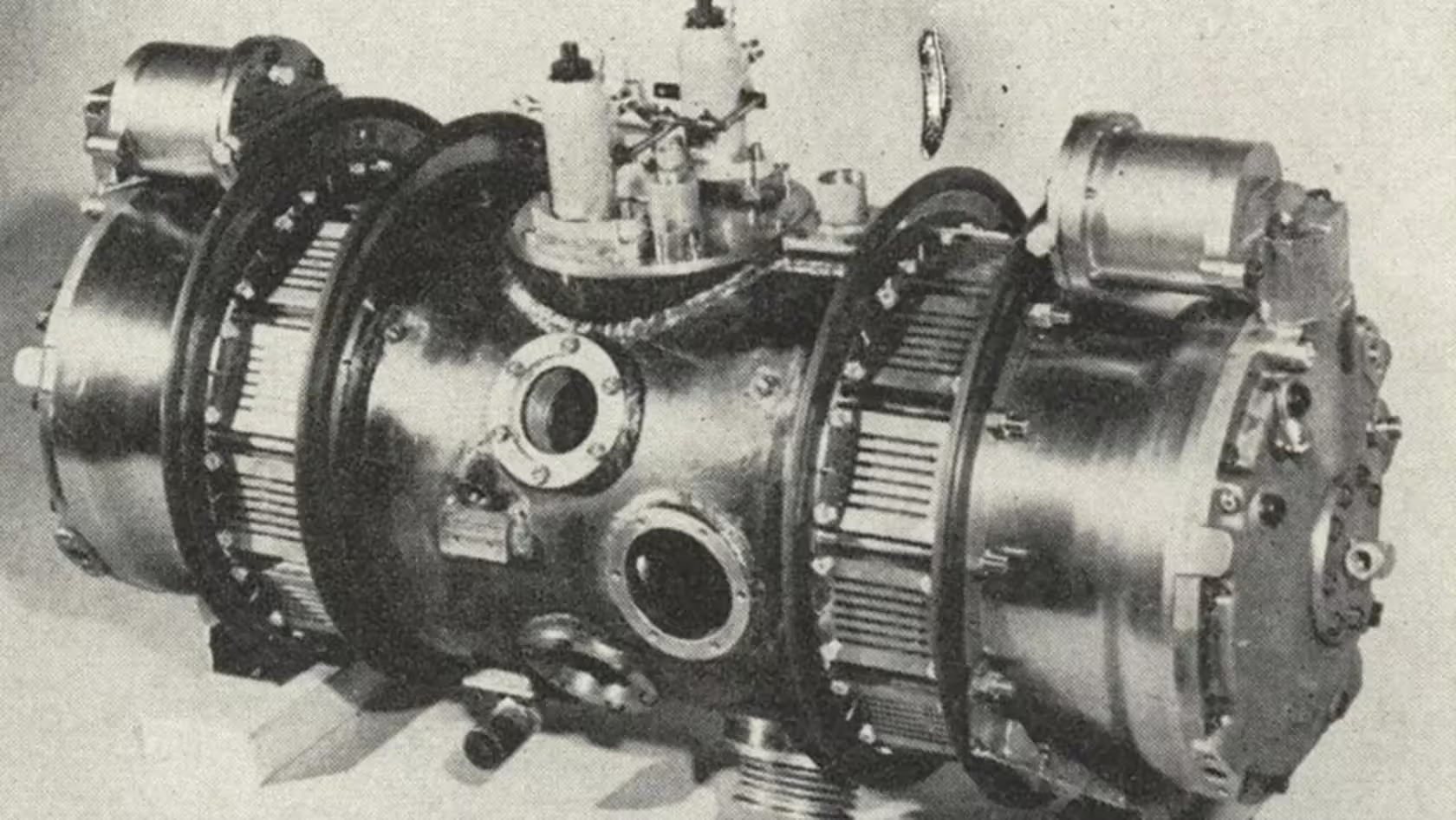

Instead, the reciprocating pistons compressed air into a surrounding chamber. That compressed air mixed with the hot exhaust gases and flowed to a balancing reservoir. This steady stream of hot gas was directed at a compact 13-centimeter turbine wheel.

Power transfer and turbine behavior

The small turbine spun extremely fast — about 10,000 rpm at idle and up to 45,000 rpm under load — and, through a geartrain, drove the tractor’s wheels and accessories. In effect, the free-piston unit acted as a gas generator: the piston assemblies produced hot working gas that powered a turbine, which provided motive power.

Engineering cleverness: lower temperatures, simpler materials

One key innovation was mixing compressed air with exhaust gases to reduce peak gas temperature to roughly 510 °C. That lower temperature meant Ford could build the turbine from common stainless steel rather than exotic, expensive alloys used in typical gas turbines — a major cost advantage. Paul Klotsch estimated that with mass production each turbine could cost as little as about $18, dramatically undercutting the price of conventional piston engines of the era.

Advantages: what made engineers excited

- Fewer moving parts compared with a conventional diesel.

- Lighter overall package than heavy agricultural diesel engines.

- Faster throttle response and strong initial acceleration compared with some gasoline engines.

- No battery required for starting; the engine used compressed air to initiate the first cycle.

These factors made the Typhoon concept attractive for tractors and other heavy equipment where reliability, fuel flexibility, and low maintenance were priorities.

Why the idea stalled: the practical challenges

Despite the promise, several tough problems prevented mass production.

- Accessory drive complexity: Without a crankshaft, components like an alternator or hydraulic pump needed to be driven off the turbine. Routing mechanical power from a very high-speed turbine complicated packaging and design.

- Inconsistent combustion characteristics: The free-piston cycle produced slightly different explosions each stroke, making precise control of piston stroke and compression ratio difficult. That variability affected efficiency and emissions.

- Noise and vibration: Although Ford claimed the turbine sound would be noticeable mainly at idle, the two-stroke-like combustion and resulting vibration proved problematic in real-world operation.

Ultimately these issues — combined with development costs and the conservatism of the market at the time — pushed the program into a dead end. Ford built at least three prototypes, and other automakers including General Motors experimented with similar concepts, but none reached full-scale production.

Legacy and modern relevance

The Typhoon isn’t just a historical curiosity. Free-piston engines continue to intrigue engineers today, especially as range-extender generators for electric vehicles and for onboard power generation. Companies like Toyota and other research groups have revisited the free-piston concept, applying modern control systems, materials, and sensors to address problems that sank earlier efforts.

Quote: "The Typhoon is a reminder that radical ideas often arrive decades before the technology catches up."

Quick specifications & highlights

- Configuration: Single horizontal cylinder with two opposing pistons

- Turbine diameter: ~13 cm

- Prototype output: Early demonstrator ~10 hp; turbine rpm 10,000 rpm idle / up to 45,000 rpm under load

- Start method: Compressed air

- Key advantage: Fewer moving parts and potential low production cost

Takeaway for car and tractor enthusiasts

Ford’s Typhoon project is a memorable chapter in automotive history — an engineering gamble that traded complexity in traditional drivetrain parts for a boldly different architecture. While it didn’t transform the industry in the 1950s, the free-piston, crankless engine remains a valuable case study for engineers and a reminder that breakthroughs can emerge from small teams working in unlikely places. As electrification reshapes the market, old ideas like the free-piston generator may find a second life as efficient, compact range extenders or power generators in hybrid and electric applications.

Whether you’re into engine design, tractor history, or automotive innovation, the Typhoon is worth remembering: a machine that dared to remove one of the internal-combustion engine’s most sacred parts — the crankshaft — and briefly rewrote what a powertrain could be.

Comments

labcore

Is the inconsistent combustion issue really fixable with modern control systems? Sounds promising, but packaging a 45k rpm turbine, noise and emissions still worry me..

turbo_mk

Wow, Ford actually gutted the crank? That shed-built prototype vibe is brilliant, and a 13cm turbine at 45k rpm sounds mad! Curious how they'd solve the vibration and accessory drive in real farms…

Leave a Comment