5 Minutes

Microplastics found inside human bones

Microplastics and smaller nanoplastics — particles derived from fossil fuels and typically smaller than 5 mm — are increasingly detected throughout the human body. A new synthesis of 62 studies indicates these particles can reach deep into skeletal tissue, including bone marrow, and may interfere with bone metabolism and growth. The review brings together evidence from human tissue analyses, animal experiments and cell-culture work to outline potential risks to skeletal health.

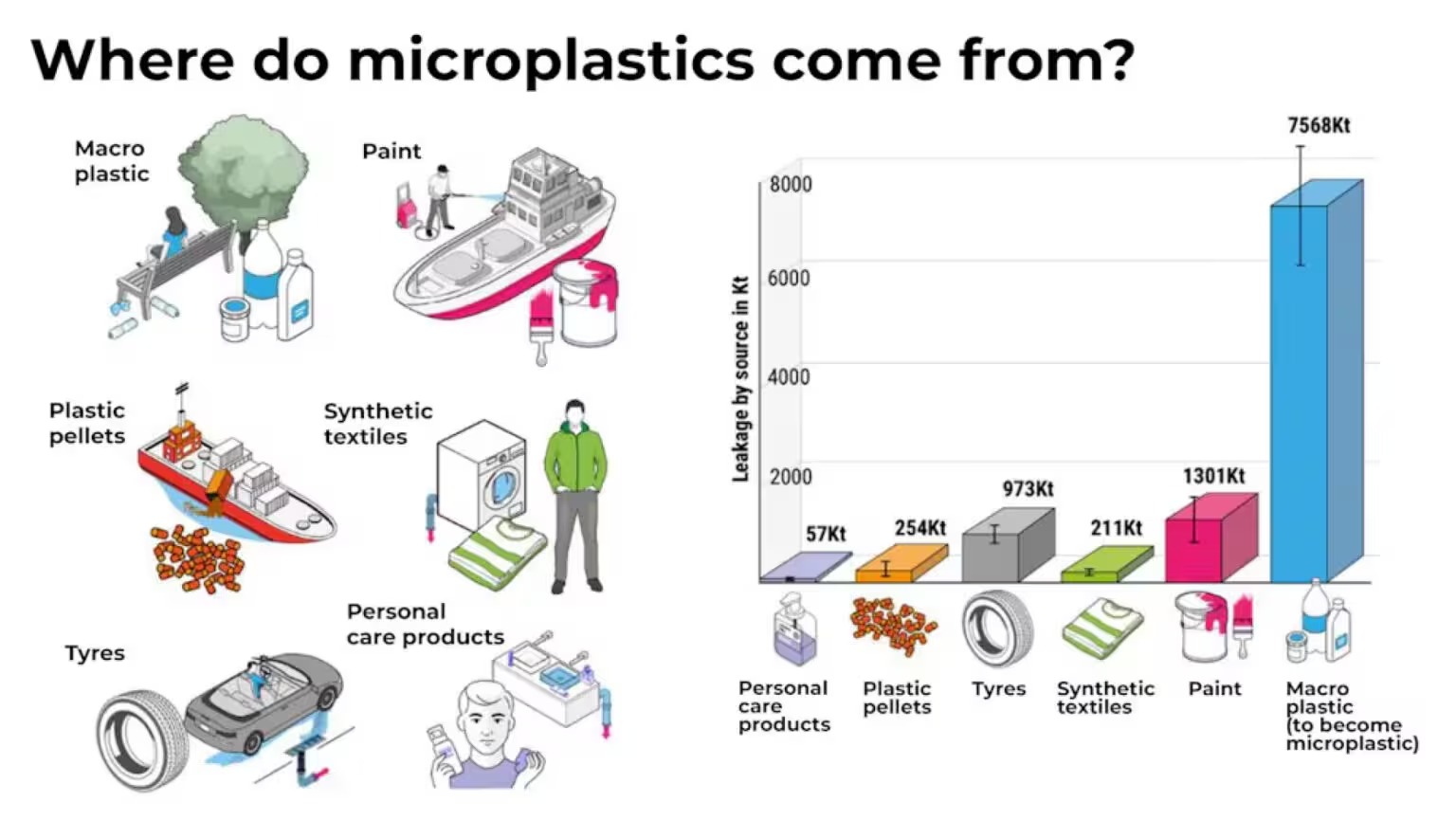

Evidence and pathways into bone

Sources of microplastic

Several human studies included in the review report microplastic particles in bone samples. The most plausible entry route is translocation from the gut into the bloodstream after ingestion, followed by distribution to organs and tissues. Animal models closely mirror this pathway: ingested microplastics migrate to internal tissues, and laboratory analyses show accumulation in bone and marrow.

At the cellular level, experiments with bone-derived cell lines reveal consistent biological effects. Microplastic exposure can reduce cell viability, accelerate cellular senescence (premature aging), shift how stem cells differentiate into bone-forming cells, and trigger inflammatory signalling. These local cellular changes are a likely mechanism behind the impaired bone formation observed in some animal studies.

Impact on bone growth and strength

Animal experiments in the reviewed literature document reduced skeletal growth following exposure to microplastics and nanoplastics. The particles appear to disrupt the balance between osteoblasts (bone-forming cells) and osteoclasts (bone-resorbing cells). When osteoclasts are altered, bone remodeling and repair can be compromised, leading to weaker bone architecture, increased deformities and a higher risk of fractures in experimental animals.

Medical scientist Rodrigo Bueno de Oliveira of the State University of Campinas, Brazil, summarized the concern: 'A significant body of research suggests microplastics can penetrate bone tissue, including the marrow compartment, and potentially disturb its metabolic function.' He notes that the observed cellular dysfunctions — inflammation, impaired viability and altered differentiation — culminate in interrupted skeletal growth in animals.

Broader public-health context

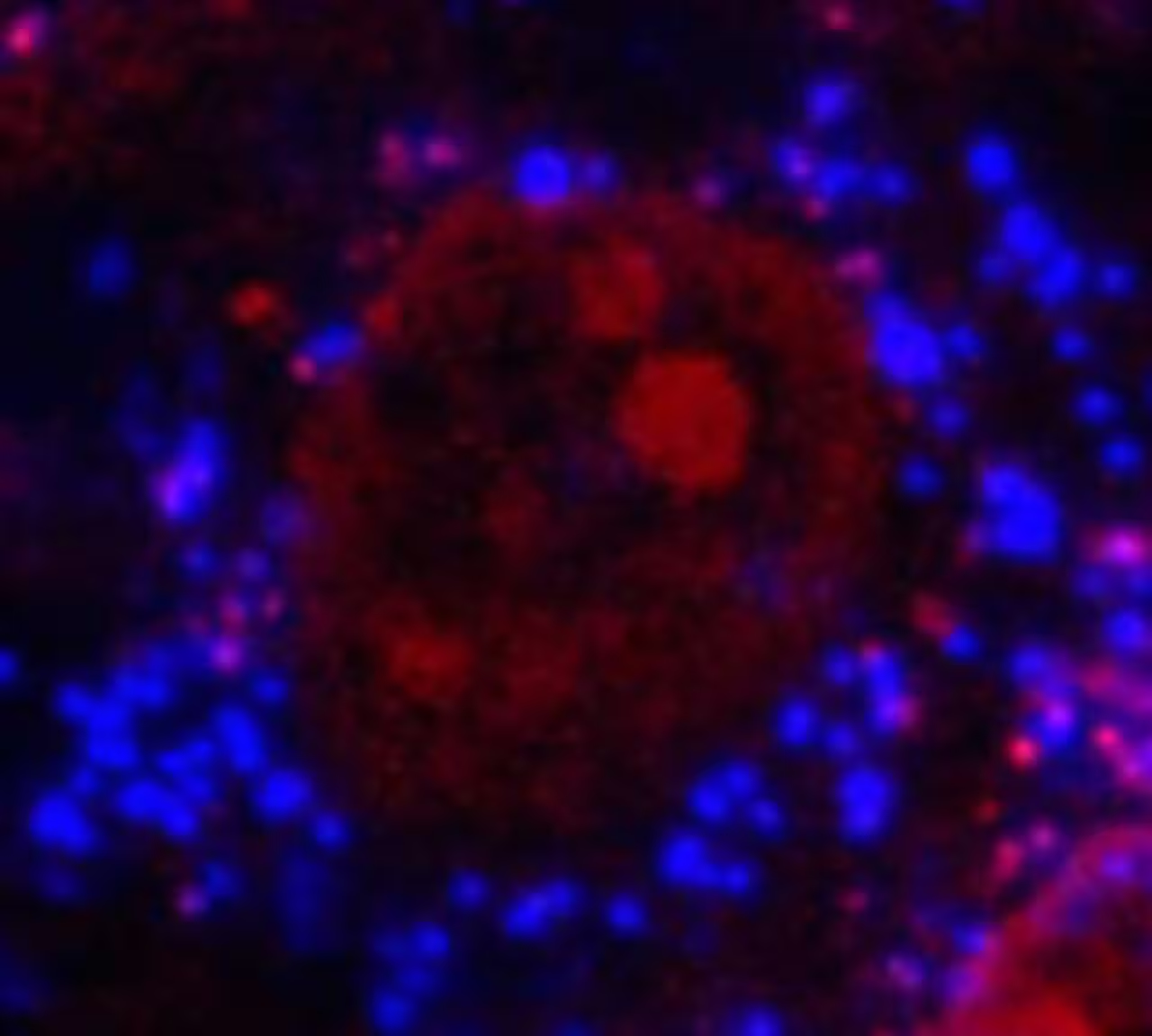

Interior of an MG-63 bone cell magnified 400x with microplastic spheres highlighted in blue and the cell nucleus in red. (Mariana Cassani de Oliveira/LEMON/FCM-UNICAMP)

Translating animal and in vitro findings to human disease remains challenging. Nevertheless, global rates of osteoporosis and age-related bone fragility are rising in many countries, driven by demographic aging and lifestyle factors such as alcohol use and physical inactivity. Researchers now consider microplastic exposure a plausible additional contributor, one that has been underrecognized during decades of plastic production.

Current production of synthetic polymers exceeds 400 million metric tons per year globally, and plastic manufacture and disposal contribute substantially to greenhouse gas emissions (around 1.8 billion metric tons of CO2-equivalent annually). These production and waste streams sustain continuous environmental and human exposure to microplastics.

Limitations and research needs

The review highlights several important knowledge gaps. Quantitative exposure–response relationships are not established for humans: we lack robust data on how much and what kinds of particles reach bone tissue over a lifetime, and what concentrations produce clinically relevant effects. Analytical challenges also remain; reliably identifying and measuring nanoplastics in biological tissues is technically difficult and requires standardized methods.

Researchers call for coordinated epidemiological studies, long-term animal experiments that use environmentally relevant particle types and doses, and improved analytical tools for detecting nanoplastics in human samples. Investment in these areas will be essential to determine whether microplastic contamination meaningfully contributes to bone disease at the population level.

Practical steps to reduce exposure

While science catches up, individuals and institutions can lower exposure risk through straightforward measures: filtering or treating drinking water to remove particulates, reducing use of single-use plastics, choosing natural-fiber clothing over synthetic textiles, and minimizing consumption from plastic bottles and food packaging.

Expert Insight

Dr. Emily Carter, an environmental toxicologist at a university research centre, commented: 'The evidence that microplastics reach deep tissues is growing. Even if direct causation of osteoporosis in people is not yet proven, the cellular effects we see in the lab — inflammation, impaired cell function and altered bone cell differentiation — are biologically plausible pathways for harm. Prioritizing better exposure assessment and standardized detection methods will let us move from concern to concrete public-health guidance.'

Conclusion

The review of 62 studies underscores a pressing scientific and public-health question: microplastics are detectable in bone and bone marrow, and experimental data show they can disrupt the cellular machinery that maintains healthy bone. Although causation in humans is not established, the combination of rising plastic production, documented tissue accumulation and plausible biological mechanisms supports calls for more targeted research and precautionary exposure reduction. Policymakers, researchers and the public should treat skeletal exposure to microplastics as a legitimate area for urgent study and risk mitigation.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment