7 Minutes

Astronomers have completed a detailed census of thousands of nearby K-type stars — the so-called orange dwarfs — and identified hundreds of mature, quiet stars that make promising targets in the hunt for habitable worlds. These stars strike a balance between longevity and calm stellar behavior, offering planets long stretches of stable conditions that could allow complex life to develop.

Why orange dwarfs matter: stability, lifespan, and habitability

When astronomers weigh which stars are most likely to host habitable planets, lifetime and stellar activity are critical factors. Some massive stars exhaust their fuel in mere millions of years — too short for life as we know it to emerge. At the other extreme, red dwarfs can survive far longer than the present age of the Universe, but their frequent energetic flares and strong ultraviolet output can strip atmospheres or sterilize planetary surfaces.

K-type stars sit in a sweet middle ground. Slightly cooler and less massive than our Sun (a G-type star), orange dwarfs are long-lived and relatively calm. While Sun-like G stars remain on the main sequence for about 10 billion years, K dwarfs can burn steadily for tens of billions of years — estimates range roughly from 20 to 70 billion years. That added longevity, combined with lower flare rates compared with many M-type red dwarfs, makes them attractive targets for studies of exoplanet habitability.

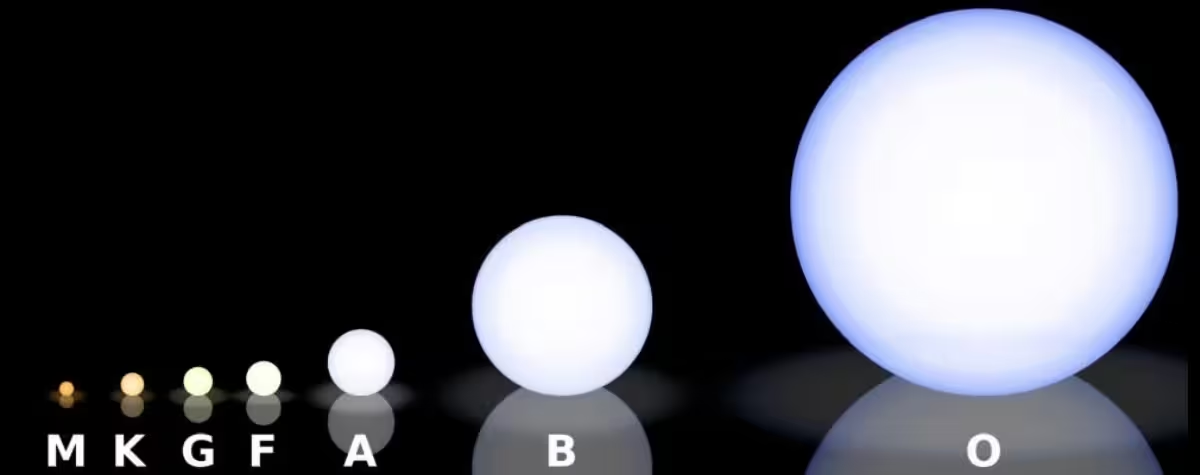

Main-sequence stars range from cool, long-lived red dwarfs (left) to hot, short-lived blue giants (right).

What the new survey did and why it matters

A team led by Sebastián Carrazco-Gaxiola at Georgia State University completed an observational census of more than 2,000 K-type stars in the solar neighborhood and obtained high-resolution spectra for hundreds. Using spectrographs on two 1.5-meter telescopes — CHIRON on the SMARTS telescope in Chile and TRES on the Tillinghast Telescope in Arizona — the team measured stellar ages, rotation rates, temperatures, chemical composition (metallicity), and galactic locations. These properties collectively determine whether a star provides a stable, long-lived environment for planets.

Presented at the American Astronomical Society meeting and described in a paper submitted to The Astronomical Journal, the survey identifies 529 mature, inactive K dwarfs within about 33 parsecs (roughly 108 light-years) as prime targets for terrestrial-planet searches. According to the NASA Exoplanet Archive, only a small fraction — about 7.5% or 44 — of these nearby K stars were previously known to host confirmed exoplanets. That gap reflects observational bias rather than a real scarcity: brighter Sun-like stars and the favorable planet-to-star mass ratios of M dwarfs have guided most earlier searches.

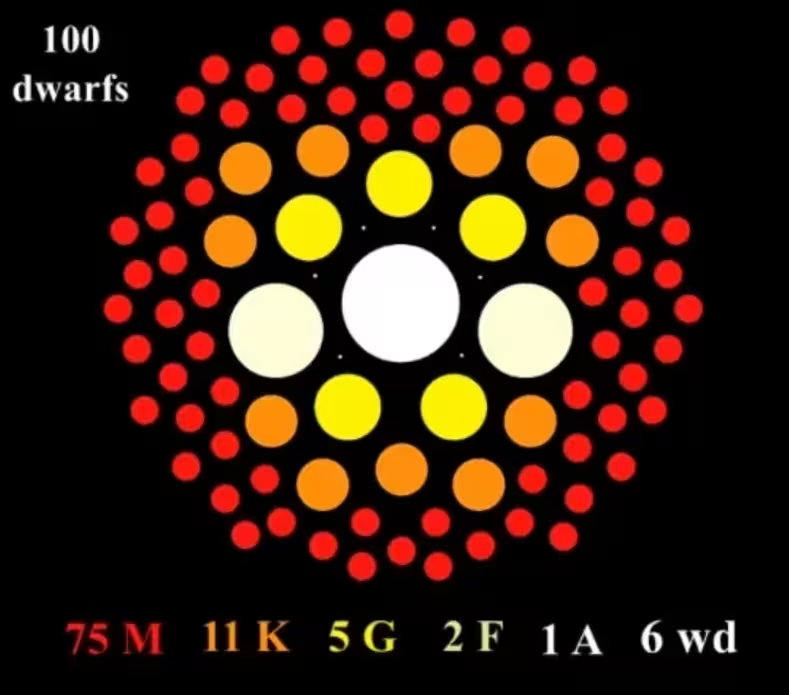

This graphic shows dwarf star types within 10 parsecs of the Sun. K-type stars are the second most common but are underrepresented in exoplanet surveys.

Survey techniques and what the spectra reveal

High-resolution echelle spectroscopy is a powerful tool for stellar characterization. By resolving thousands of spectral lines, astronomers infer surface temperatures, elemental abundances, and rotation velocities. Rotation slows as stars age, so spin rates can act as a clock for stellar maturity. The survey used these diagnostics to separate young, active K dwarfs (which often show more magnetic flaring and high-energy radiation) from older, quiescent stars that are friendlier to planetary atmospheres.

All-sky coverage was essential. With complementary spectrographs in both hemispheres, the team could observe K dwarfs across the full sky, minimizing selection biases tied to telescope location. Identifying stars in the Milky Way's thin disk — where metallicity tends to be higher and the environment less hostile — also helps prioritize targets likely to have rocky planets with substantial atmospheres.

Implications for exoplanet searches and future missions

Survey catalogs like this one act as a filter: they let planet hunters focus valuable telescope time and instrumentation on the most promising nearby systems. Instruments that search for small, Earth-sized planets by radial velocity or transit methods benefit when stellar noise is low and stellar parameters are well known. Similarly, future direct-imaging missions and next-generation space telescopes will need carefully vetted target lists to allocate costly observing time to systems most likely to reveal biosignatures or atmospheric signs of habitability.

Todd Henry, a senior author on the study and distinguished professor at Georgia State University, noted that this database will underpin decades of follow-up work and, far into the future, may point to destinations for interstellar probes when that becomes feasible.

Potential caveats and remaining questions

Although K dwarfs are promising, not every orange dwarf will host habitable planets. Planet formation depends on local disk chemistry, migration history, and chance. Metallicity measurements improve estimates of rocky-planet likelihood, but only direct planet detections can confirm habitability potential. Moreover, even quiescent stars can host sporadic flares or magnetic cycles that affect atmospheres over long timescales, so ongoing monitoring remains important.

Expert Insight

'K-type stars give us a long, steady laboratory to study atmospheres and climate evolution on other worlds,' says Dr. Maya Richardson, an exoplanet researcher at the Institute for Planetary Sciences. 'Because these stars change slowly over billions of years and tend to be less eruptive than many red dwarfs, planets have a better chance to hold onto atmospheres and develop complex chemistry. That doesn't guarantee life, but it raises the odds and makes K dwarfs an efficient place to search.'

Richardson adds that combining high-resolution spectroscopy with space-based transit surveys and precision radial-velocity instruments will be key to turning the survey's candidate list into a roster of confirmed, characterizable worlds.

What to watch next

- Follow-up radial-velocity and transit observations to discover Earth-size planets around the identified K dwarfs.

- Long-term monitoring for stellar activity cycles to refine which stars remain truly quiescent over timescales relevant to biology.

- High-contrast imaging and spectroscopy with future telescopes to probe atmospheres for water vapor, oxygen, methane, and other biosignature gases.

By narrowing thousands of nearby stars to a few hundred high-priority targets, the survey helps focus the search for life in our cosmic neighborhood. The orange dwarfs may not be as flashy as massive blue stars or as numerous as faint reds, but their quiet persistence could make them our best bet for finding worlds where life had the time and stability to flourish.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

skyspin

Seems plausible but is the 529 count biased by detection limits? Only 44 known planets, hmm telemetry bias much, need more transits and RV followup

astroset

Whoa, orange dwarfs sound like sleeper hits for life, tens of billions of years? mind blown. But what about those rare flares, still nervous...

Leave a Comment