5 Minutes

Time-restricted eating (TRE), a popular form of intermittent fasting, promises better metabolism and heart health by compressing daily eating into a shorter window. A new controlled trial from the German Institute of Human Nutrition Potsdam-Rehbruecke (DIfE) complicates that promise, suggesting calories may matter more than the clock itself.

What the trial tested and why it matters

Researchers enrolled 31 women with overweight or obesity and assigned them to two TRE schedules for two weeks each: an early window from 8am to 4pm, and a later window from 1pm to 9pm. Importantly, participants were allowed to eat their usual foods and maintain roughly the same total daily calories, making this an isocaloric study designed to isolate the role of timing rather than calorie reduction.

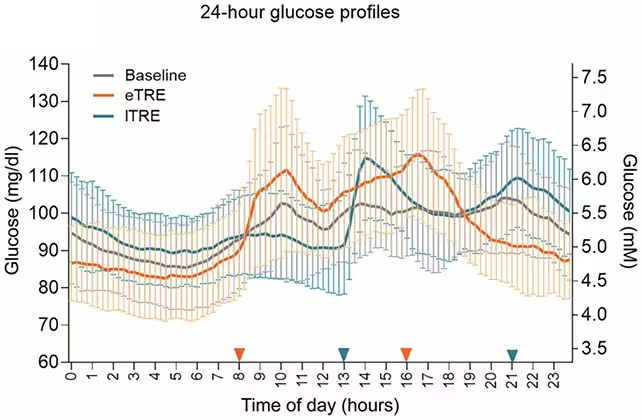

The team measured key metabolic and cardiovascular indicators: fasting glucose, blood pressure, cholesterol, body weight, and markers tied to circadian rhythm. If timing alone were a powerful metabolic lever, the study would show improvements in these markers independent of calorie intake.

Surprising results: modest weight loss, no metabolic wins

After each two-week TRE period, participants experienced small drops in body weight, but the study did not find the expected changes in blood sugar, blood pressure, or cholesterol. In short, compressing the eating window without cutting calories did not produce clear cardiometabolic benefits over the short term.

The researchers note that previous studies reporting benefits from TRE may have mixed effects of reduced calorie intake with timing, meaning that calorie restriction could be the main driver of improved metabolic markers rather than the act of restricting eating hours.

The paper states that in this nearly isocaloric trial, no improvements in metabolic parameters were observed after two weeks of TRE. That phrasing highlights a narrowing of what TRE alone can be expected to do for metabolic health, at least in short-term, small-sample settings.

The researchers looked at health indicators like glucose levels

Body clocks shifted, showing another layer of influence

Although classic metabolic measures remained unchanged, TRE did shift participants' circadian timing. Eating earlier or later nudged internal clocks tied to sleep and other daily rhythms, confirming that meal timing can reset biological timing cues. That shift could still be meaningful: eating late at night is associated in other studies with poorer metabolic outcomes, and TRE may help prevent those patterns when it indirectly reduces late-night intake.

'Those who want to lose weight or improve their metabolism should pay attention not only to the clock, but also to their energy balance,' says biologist and nutritionist Olga Ramich of DIfE, underscoring the study's practical takeaway: timing can be useful, but it is not a magic bullet if calorie intake remains unchanged.

Context and limits: small sample, short duration

This trial is valuable because of its controlled isocaloric design, but it has limitations. Two weeks is a brief interval to capture longer-term metabolic adaptations, and the sample size of 31 women limits generalizability. Different populations, other TRE windows, and longer follow-ups could show different effects.

Researchers emphasize that calorie restriction under TRE might still produce additive benefits. In other words, if TRE leads to reduced calories in practice, both mechanisms could work together to improve glucose control, lipids, and blood pressure. The team calls for further research on whether hypocaloric TRE, individual differences in optimal meal timing, or longer trials yield clearer metabolic advantages.

Practical takeaways for readers

- If your goal is metabolic improvement, pay attention to calorie balance as well as when you eat.

- TRE can shift circadian rhythms, which may reduce harmful late-night eating patterns for some people.

- Short-term, isocaloric TRE may not lower blood sugar or cholesterol on its own; long-term studies and calorie-restricted versions of TRE remain important to test.

Expert Insight

'This study helps separate two effects that are often conflated in fasting research,' says Dr. Emily Hart, a hypothetical nutrition scientist familiar with circadian metabolism. 'Timing influences the body clock and behavior. Calorie restriction influences energy balance and metabolic markers. The interaction between the two is where future breakthroughs are likely to come.'

The DIfE trial adds nuance to how clinicians and the public should approach intermittent fasting. For individuals and practitioners, the takeaway is pragmatic: use timing to shape habits and sleep-friendly schedules, but do not rely on timing alone to correct insulin resistance or cardiovascular risk factors without addressing overall calorie intake and diet quality.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

Armin

wow, didn't expect null metabolic gains — but clock shifts are cool. TRE might work by changing habits, not magic. If that sticks, could help sleep and…

bioNix

Is the effect just calories not timing? seems likely, but 31 ppl and 2 weeks is tiny sample… curious about longer trials, other ages, diet quality too

Leave a Comment