7 Minutes

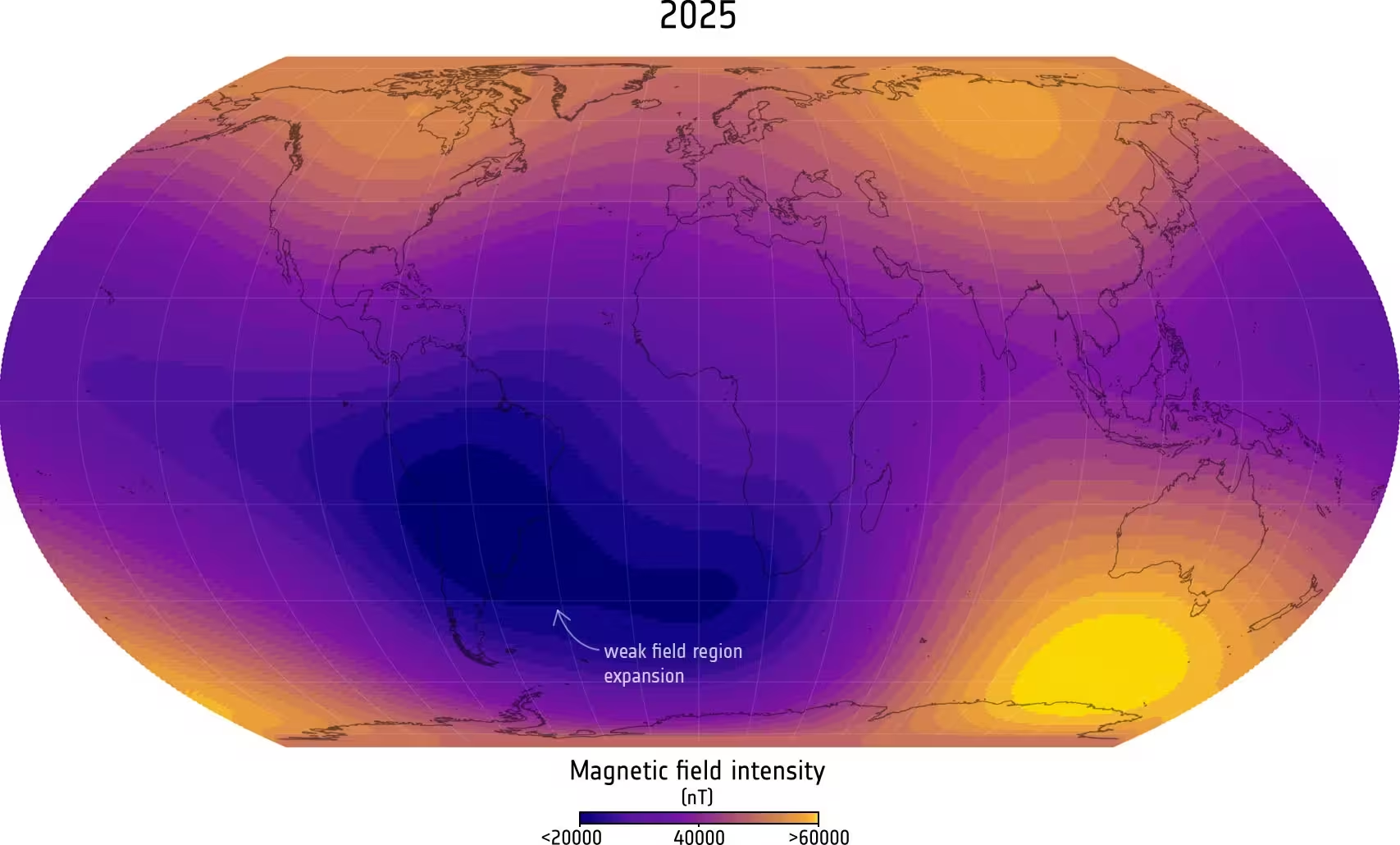

Long-term satellite observations reveal that a weakening patch in Earth's magnetic shield over the South Atlantic has grown dramatically in the past decade. New analyses of data from ESA's Swarm mission show the anomaly has expanded by an area almost half the size of continental Europe since 2014, driven by shifting flows deep inside our planet.

A mysterious weak spot that keeps growing

The South Atlantic Anomaly (SAA), first noted in the 19th century southeast of South America, is a region where Earth's magnetic field is markedly weaker than elsewhere. Using 11 years of precision measurements from ESA's Swarm satellite constellation, scientists have documented a steady expansion of this weak zone between 2014 and 2025. In particular, the SAA has been weakening more rapidly since about 2020 in a section of the Atlantic southwest of Africa, effectively enlarging the anomaly by an area comparable to nearly half of Europe.

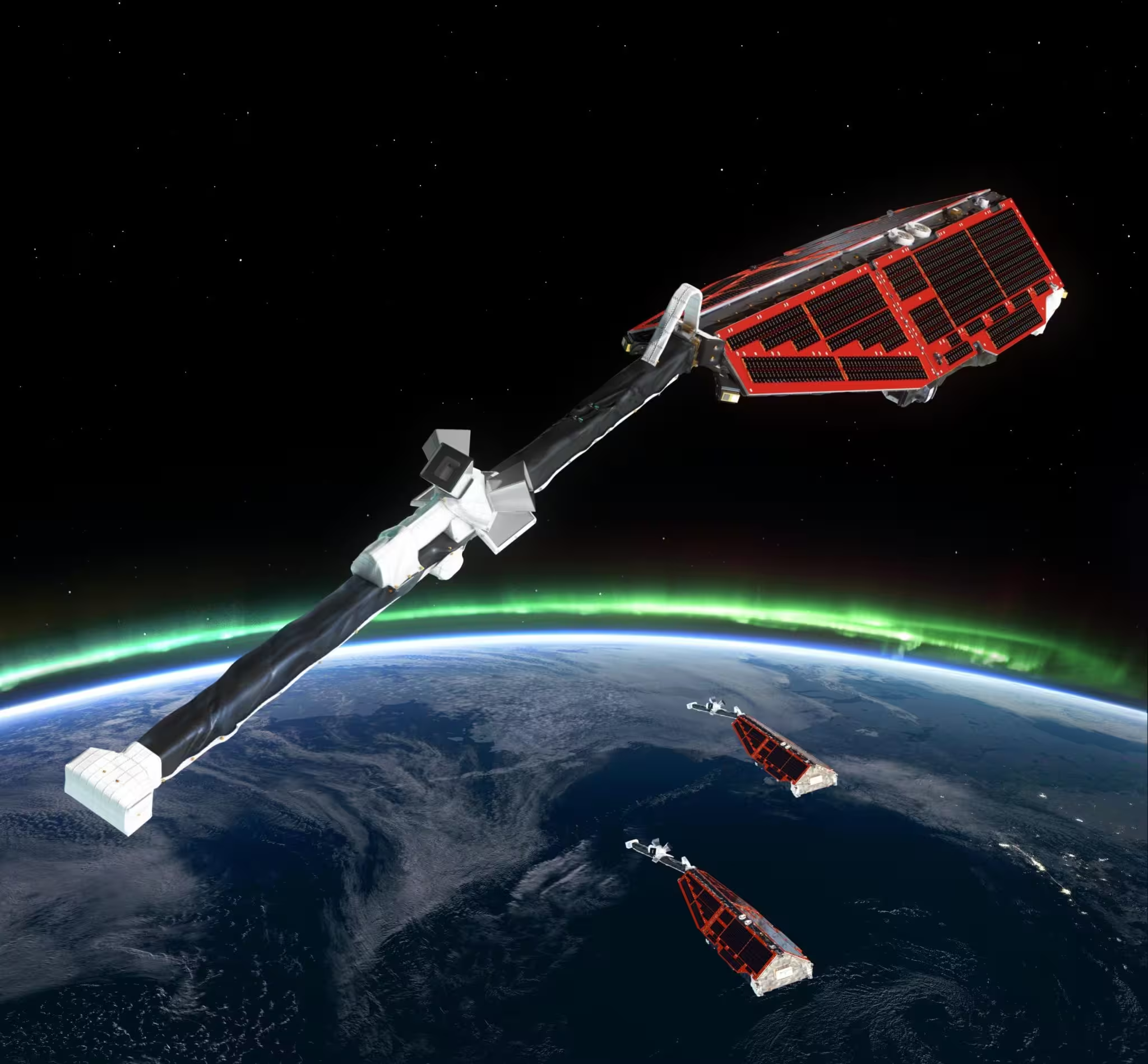

Swarm is ESA's first dedicated magnetometry constellation, designed to separate magnetic signals produced by Earth's core, mantle, crust, oceans, ionosphere and magnetosphere. The mission's three identical satellites provide the continuous, high-resolution records needed to tease apart these sources and reveal how the planet's protective field is changing over time.

Swarm is ESA’s first constellation of Earth observation satellites designed to measure the magnetic signals from Earth’s core, mantle, crust, oceans, ionosphere and magnetosphere, providing data that will allow scientists to study the complexities of our protective magnetic field.

What's happening in the core: reverse flux patches and westward motion

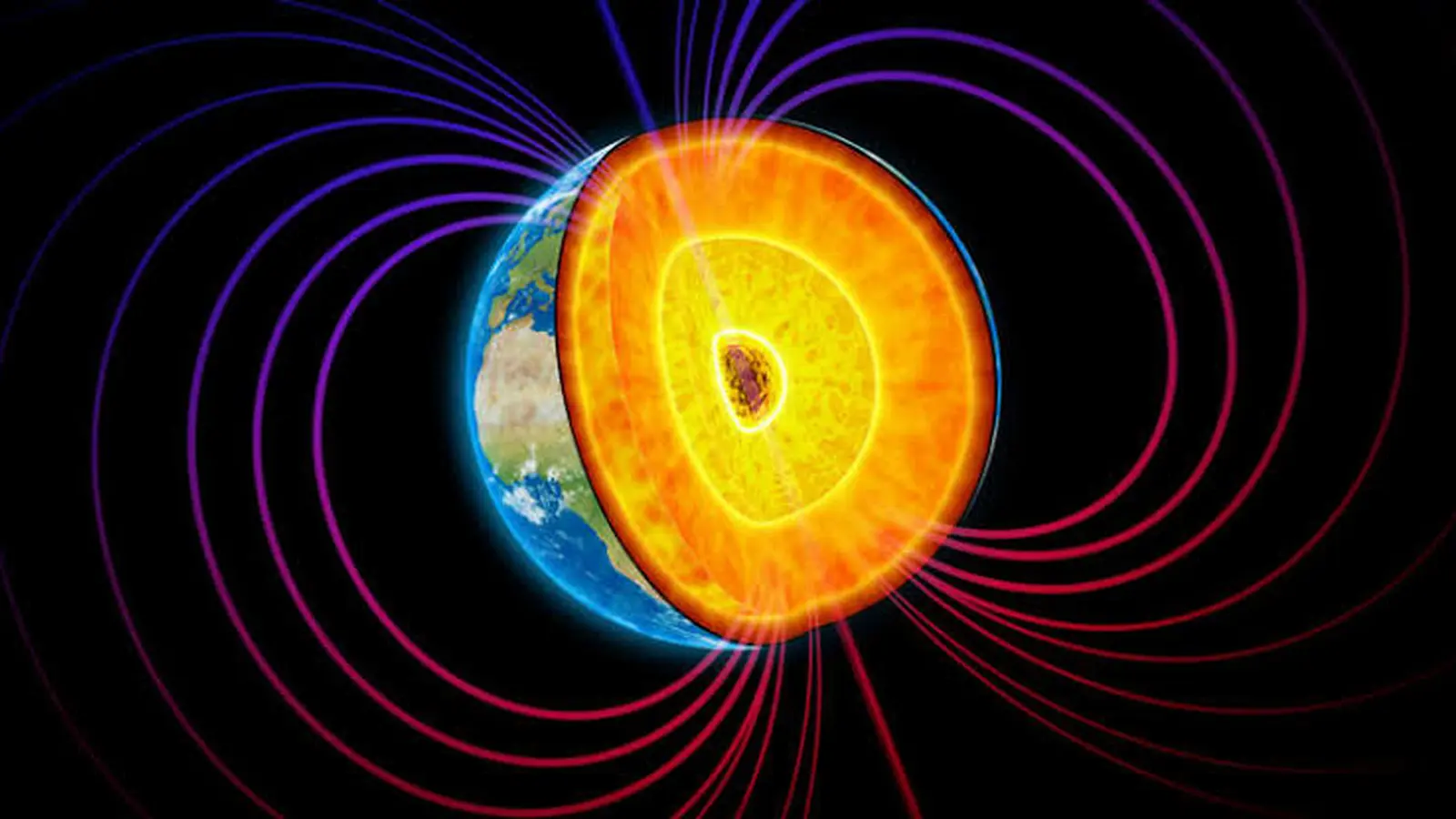

Earth's magnetic field originates in the liquid iron outer core about 3,000 kilometers below the surface. Convection in that electrically conducting fluid creates electrical currents and, in turn, the geomagnetic field. But the core's flows are turbulent and variable, producing complex, evolving patterns rather than a neat bar-magnet dipole.

Researchers link the SAA's unusual behavior to so-called reverse flux patches at the boundary between the outer core and the overlying rocky mantle. In these locations the magnetic field lines, instead of emerging outward from the core as typical, bend back into the core. According to lead author Professor Chris Finlay of the Technical University of Denmark, one of these reverse flux patches is moving westward across the African region and intensifying the weakening there. This heterogeneous behavior means the anomaly is not a single, uniform block but a patchwork changing in different ways toward Africa and toward South America.

South Atlantic Anomaly 2025 compared to 2014

Why the anomaly matters for satellites and space operations

The SAA is more than a geophysical curiosity: it has practical consequences for space hardware. Satellites that pass through the anomaly experience higher fluxes of energetic charged particles trapped in Earth's magnetosphere, increasing radiation exposure to onboard electronics and sensors. Effects range from single-event upsets and degraded instrument performance to temporary outages and accelerated aging of components. For engineers and mission planners, tracking the SAA's size, location and intensity is essential to mitigate risks to low-Earth orbit spacecraft, including scientific missions, telecommunications satellites and human-rated systems.

Beyond satellite safety, changes in Earth's magnetic field also affect navigation systems that rely on magnetic models and influence how auroras and radiation belts respond to space weather. The dynamic behavior observed by Swarm underscores the need for continual monitoring to update operational models used by aviation, shipping and geolocation services.

Swarm's decade-plus record: unprecedented continuity

Launched on 22 November 2013 as part of ESA's Earth Explorer program, the three Swarm satellites have provided the longest continuous space-based record of geomagnetic measurements to date. Originally conceived as technology demonstrators, these spacecraft have far exceeded their planned lifetimes and are now indispensable for global magnetic models, space weather monitoring and research into core dynamics.

The dataset from Swarm underpins operational magnetic field models used for navigation and is crucial for separating signals from the core, crust and space environment. Anja Stromme, Swarm Mission Manager at ESA, noted that the constellation remains healthy and hopes to extend observations beyond 2030, when the approaching solar minimum will allow exceptionally clean measurements of the core field.

Shifting magnetic highs: Siberia grows while Canada shrinks

Swarm's latest analyses show the magnetic field is not simply weakening globally: some regions have strengthened. In the Northern Hemisphere two strong-field regions exist around Canada and Siberia; in the Southern Hemisphere a strong region is present in parts of the south. Since Swarm's launch, the Siberian strong-field area has expanded by roughly 0.42% of Earth's surface area, an increase comparable in size to Greenland, while the Canadian strong-field area shrank by about 0.65% of the planet's surface, an area similar to India.

These redistributions are linked with the north magnetic pole's drift toward Siberia and are driven by complex flows in the core. The shifting balance between these high-field regions affects magnetic declination and can influence navigation systems that still rely on magnetic references.

Expert Insight

Dr. Maya Patel, a geophysicist specializing in core dynamics, offers a perspective on why continuous monitoring matters: "The core is a chaotic engine. Small changes in flow patterns can reorganize magnetic features at the surface over a few years. Swarm's long baseline is the only way we can detect these reorganizations in real time and feed them into models used by industry and science. Without this sustained record, we'd be blind to the subtle precursors of larger field rearrangements."

Scientific context and what comes next

The observed expansion of the SAA highlights the coupling between fluid motions in the core and the magnetic field we measure at the surface and in near-Earth space. To translate observations into predictive ability, scientists combine satellite records with numerical models of core flows and mantle conductivity. Continued Swarm operations, together with ground observatories and upcoming missions, will improve our understanding of phenomena such as geomagnetic jerks, secular variation, and the long-term trend toward field reversals or excursions.

For space agencies and satellite operators, the immediate priorities are updating radiation exposure maps, hardening sensitive systems, and refining orbital planning to reduce time spent in high-radiation regions. For researchers, the SAA provides a natural laboratory to study core dynamics in action and to test models that connect deep Earth processes with space weather impacts.

As Swarm's record grows, so too does our ability to watch Earth's invisible shield evolve. That continuous, detailed view is essential—not only for pure science but for the practical task of protecting satellites and services that modern societies now depend on.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

mechbyte

Wow didnt expect the SAA to expand so fast! Satellites and nav systems gotta adapt, yikes. if that keeps up...

geoFlux

Is this even true? SAA grew almost half of Europe since 2014… sounds alarming. But are we sure it's not a data artefact or model bias? curious

Leave a Comment