6 Minutes

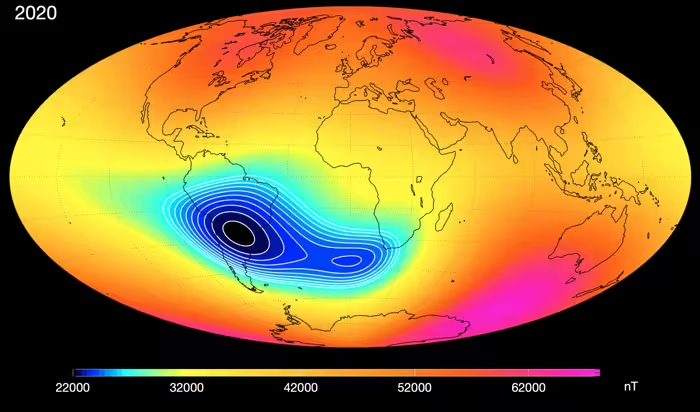

Across the skies between South America and southwest Africa lies a curious and expanding weakness in Earth's magnetic shield. Known as the South Atlantic Anomaly (SAA), this vast region of reduced magnetic intensity doesn’t endanger people on the ground, but it creates real headaches for spacecraft and offers scientists a rare window into how our planet’s magnetic engine behaves.

What the South Atlantic Anomaly is — and why it matters to satellites

The SAA is a large patch where Earth’s magnetic field is unusually weak compared to surrounding regions. Generated by the planet’s geodynamo — the turbulent flow of molten iron in the outer core — Earth’s magnetic field is typically modeled as a dipole, like a bar magnet. But the actual field is a complex superposition of multiple sources and irregularities, and the SAA is one of the most prominent.

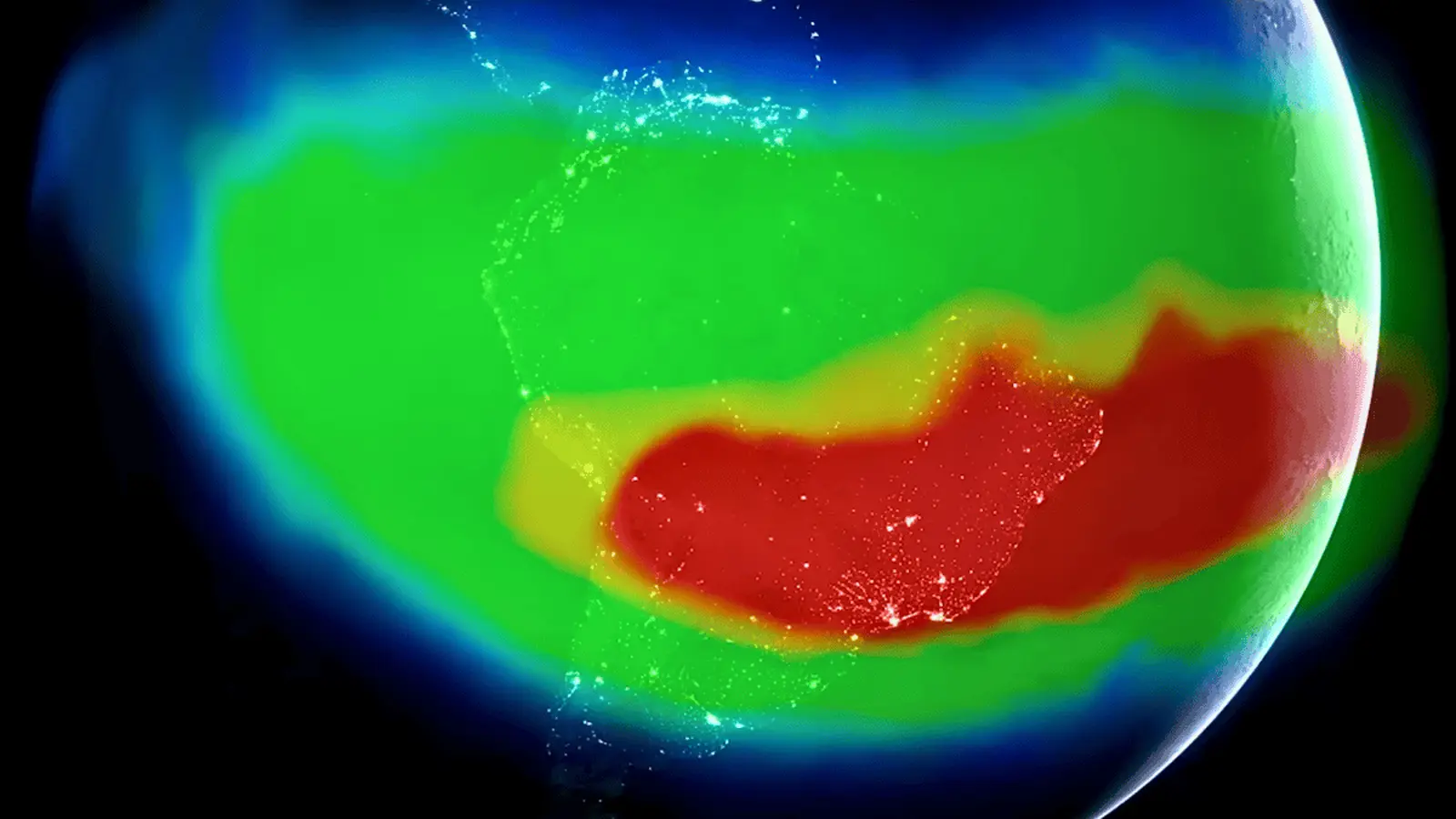

In practical terms, a weaker magnetic field over the South Atlantic allows more high-energy charged particles from the Sun and the Van Allen radiation belts to reach low-Earth orbit. Satellites, CubeSats and even the International Space Station (ISS) pass through this zone regularly. When electronics onboard are struck by solar protons and energetic particles, they can suffer transient glitches, data corruption, or in worst-case scenarios, permanent hardware damage. To reduce risk, spacecraft operators sometimes shut down or place sensitive systems into safe mode before crossing the anomaly.

The anomaly is changing: growth, drift and splitting

NASA and international missions tracking the geomagnetic field have documented important changes in the SAA over recent years. Since about 2014, the anomaly has expanded significantly — by roughly half the size of continental Europe — while its magnetic intensity has further weakened. Observations show the SAA also drifts slowly, and researchers monitoring measurements from CubeSats and other instruments have confirmed this migration.

Perhaps more surprisingly, studies published around 2020 found evidence that the SAA may be dividing into two centers of minimum intensity — two distinct "cells" within the larger weakened region. That morphological change complicates efforts to model the anomaly and predict its future behavior.

Satellite data suggesting the SAA is dividing

Who’s watching and how

- NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and heliophysics teams track the anomaly using satellite data and models.

- ESA’s Swarm mission — a constellation of three satellites — provides high-resolution mapping of the geomagnetic field and has highlighted differing changes over Africa versus South America.

- Cognitive networks of small satellites (CubeSats) are increasingly important for validating field models and monitoring short-term variations.

What causes the SAA? Deep-Earth dynamics and surface signatures

At the heart of the SAA problem is Earth’s geodynamo. The dominant field source is the motion of molten iron in the outer core thousands of kilometers beneath our feet. But deep structures can modulate that field. A massive, dense region under Africa — known to seismologists as the African Large Low Shear Velocity Province (LLSVP) and located near the core-mantle boundary — is suspected of perturbing flows in the core and, consequently, the generated magnetic field.

Geophysicists like Terry Sabaka and Weijia Kuang at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center describe the SAA as the result of complex interactions among multiple field contributions. In particular, a localized region of reversed or reduced polarity has grown in the SAA area, weakening the total field locally and producing the pronounced minimum we measure in space.

Recent discoveries and long-term perspective

New research continues to refine our picture. A 2016 study led by NASA heliophysicist Ashley Greeley showed the slow drift of the SAA, while CubeSat observations in 2021 confirmed movement and structure. A 2020 geological study suggested the pattern behind the SAA might be recurrent over millions of years, implying the anomaly may not be an unusual short-term fluke but rather a long-lived feature of Earth’s magnetic history. Importantly, that research indicates the SAA is unlikely to be a direct precursor to a global geomagnetic reversal — events that do occur over geological timescales but are not triggered by a single regional anomaly.

Additional work reported in 2024 connected SAA variability to changes in auroral patterns, demonstrating that fluctuations in the field have detectable effects on space weather signatures visible in the upper atmosphere.

How scientists and engineers respond

Monitoring the SAA is both a scientific priority and an operational necessity. For satellite operators, mitigation strategies include scheduling sensitive operations around anomaly crossings, placing instruments into safe modes, using radiation-hardened components, and building redundancy into critical systems. For scientists, continuous observations from missions like Swarm, NASA satellites, and distributed CubeSat constellations supply the data needed to improve geomagnetic models and forecast changes.

Because the SAA changes slowly but unpredictably in shape, intensity and position, long-term, coordinated monitoring remains essential. These measurements help refine predictive models of the geomagnetic field, which in turn support navigation, communication, and space exploration systems that depend on accurate field maps.

Expert Insight

"The South Atlantic Anomaly gives us a natural laboratory for testing geodynamo models and for improving how we protect spacecraft from space weather," says Dr. Maya Singh, a space physicist who works with satellite mission planning. "Tracking subtle shifts in the SAA helps engineers design better radiation mitigation and helps physicists understand core–mantle interactions. It’s a slow-moving puzzle, but it has outsized practical consequences for satellites in low-Earth orbit."

In short, the SAA sits at the intersection of deep-Earth physics and modern space operations. It doesn't threaten life on Earth, but it highlights how planetary-scale processes can influence the technologies humans rely on above the atmosphere. Continued international observation and multidisciplinary research will be essential to untangle the anomaly’s causes and to protect spacecraft as it evolves.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

skyspin

No way, that's wild! The idea that deep mantle stuff under Africa can mess with satellites up above blows my mind. Space and core linked, huh

labcore

Wait, the SAA might be splitting into two cells? sounds wild. Models vs short-term noise, how confident are researchers, and could satellites really be at that much extra risk if that's real…

Leave a Comment