6 Minutes

Prenatal environment and lifelong anxiety risk

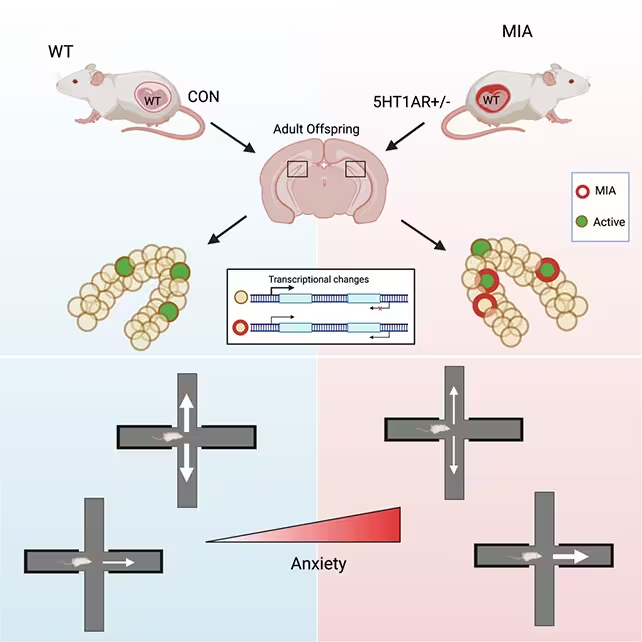

Recent experimental work in mice suggests that vulnerability to anxiety in adulthood can originate before birth. Researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine report that maternal infection or stress during pregnancy can leave durable molecular and circuit-level signatures in the offspring’s brain that increase anxiety-like behavior later in life. The study identifies specific changes in the ventral dentate gyrus (vDG), a hippocampal subregion involved in threat evaluation and avoidance, and links those changes to epigenetic reprogramming of neuronal gene regulation.

Study design: modeling maternal inflammation

To probe how prenatal adversity affects brain development, the team used genetically engineered mouse models that mimic elevated inflammatory signaling in a pregnant dam. This approach recreates aspects of maternal infection or sustained physiological stress without passing any altered stress-response genes directly to the pups. The investigators then followed the offspring into adulthood and analyzed behavior, neural activity, and DNA modifications in targeted brain regions.

The researchers concentrated on male offspring for behavioral tests because the males in their model displayed more pronounced anxiety-like behaviors. Although these males were genetically normal (they did not inherit the engineered inflammatory predisposition), as adults they showed consistent signs of heightened anxiety—such as a strong preference for enclosed spaces and avoidance of open areas—compared with control animals.

Neural circuits: overactive neurons in the ventral dentate gyrus

When threatened, the affected mice exhibited excessive activation in a subset of neurons within the ventral dentate gyrus (vDG). The vDG contributes to assessing potential threats in the surrounding environment and gating behavioral responses; overactivation in this area can amplify threat signals and bias animals toward avoidance. As the study’s authors describe, prenatal adversity left lasting imprints on vDG neurons that changed how these cells responded to unsafe contexts in adulthood.

"Our data reveal prenatal adversity left lasting imprints on the neurons of the vDG, linking gestational environment to anxiety-like behavior," said neuropharmacologist Miklos Toth, a co-author on the paper. "This mechanism may help explain the persistent stress sensitivity and avoidance seen in some individuals with innate anxiety."

Epigenetic reprogramming: DNA methylation and gene expression

To explore molecular mechanisms, the researchers measured DNA methylation patterns in neuronal tissue from the vDG. DNA methylation is an epigenetic tag that can silence or modulate gene activity without changing the underlying DNA sequence. They found thousands of differentially methylated sites in the vDG of prenatally stressed mice, particularly concentrated in gene regions that regulate synaptic communication and neuronal excitability.

These epigenetic modifications were concentrated in a small fraction of vDG neurons. "A mouse may have almost 400,000 cells in the vDG, but only a few thousand are impacted during pregnancy," Toth noted. When placed in a threatening context, the reprogrammed neurons showed amplified activity—consistent with a circuit primed to overestimate danger and favor avoidance.

Molecular neuroscientist Kristen Pleil, another co-author, summarized the functional consequence: "Overall, these epigenetic changes are instructing certain neurons in the vDG to respond differently in adulthood when faced with unsafe environments. The neurons show too much activity, ultimately contributing to the mice perceiving the environment as more threatening than it actually is."

Mice exposed to stress in the womb were shown to be more anxious as adults.

Scientific context and implications

Anxiety disorders rank among the most common mental health conditions worldwide; epidemiological studies suggest nearly one in three people may experience clinically significant anxiety during their lives. Prior human and animal studies have linked prenatal health—such as maternal infection, nutrition, and stress—to increased rates of mood and anxiety disorders in offspring. This new mouse study pinpoints a plausible mechanistic chain: maternal inflammation → targeted epigenetic changes in a threat-evaluation circuit → long-term hypersensitivity to stress and avoidance behavior.

By mapping both circuit-level hyperactivity and associated DNA methylation changes, the research adds to a growing body of evidence that early-life environments can program brain function via stable molecular tags. That raises the possibility of new diagnostic biomarkers—epigenetic signatures detectable in accessible tissue—or targeted therapies that reverse maladaptive circuit priming.

Future directions and translational challenges

The authors emphasize important caveats: these results come from controlled mouse models, and translating findings to humans requires care. Key unanswered questions include why only a subset of vDG neurons acquire the epigenetic marks and whether comparable methylation signatures appear in peripheral tissues that are easier to sample. The team plans to map the developmental time windows most sensitive to maternal inflammation and to test interventions that could normalize vDG activity and behavior.

From a public-health perspective, the study reinforces the value of prenatal care and infection control during pregnancy. It also highlights how subtle changes in gestational environment can produce durable changes in neural circuits that shape behavioral tendencies decades later.

Expert Insight

"This work is an elegant example of how prenatal conditions can sculpt specific neural circuits through epigenetic mechanisms," says Dr. Elena Vargas, a developmental neuroscientist not involved in the study. "While the jump to human anxiety disorders is nontrivial, the combination of behavioral assays, circuit mapping, and DNA methylation profiling in one study strengthens the biological plausibility. Future translational steps should focus on identifying peripheral biomarkers and defining therapeutic windows for intervention."

Conclusion

The Weill Cornell study offers mechanistic evidence that maternal inflammation during pregnancy can predispose offspring to heightened anxiety by reprogramming a discrete population of neurons in the ventral dentate gyrus. Although demonstrated in mice, these findings clarify how prenatal experiences can leave lasting molecular and circuit-level marks that influence behavior. Continued work is needed to determine whether similar epigenetic signatures exist in humans and whether they can be used for early diagnosis or targeted therapies to reduce lifelong anxiety risk.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment