7 Minutes

As launches, constellations and plans for the Moon and Mars multiply, the growing cloud of discarded satellites and rocket parts threatens to make low Earth orbit a hazardous, wasteful environment. Researchers now argue that the solution is not just better avoidance or cleanup, but a systemic move toward a circular space economy where materials and designs are built for reuse, repair and recycling.

Why orbital debris is an urgent systems problem

Space debris is more than an inconvenience. Fragmentation events — collisions, explosions from leftover propellant, and spontaneous disintegration — account for roughly 65% of trackable orbital debris. Decommissioned spacecraft and spent rocket bodies make up about 30%, while mission-related objects released during operations contribute the remaining 5%. This imbalance has produced a self-reinforcing cycle: more fragments increase collision risk, which creates still more fragments, raising the long-term hazard to active satellites and crewed missions.

Beyond the immediate danger to active assets, current practice treats expensive, high-performance hardware as disposable. Satellites that complete their operational life are often abandoned in graveyard orbits or left as debris, and re-entry options are rarely implemented at scale. On Earth, we learned the hard way that linear consumption leads to environmental and economic costs; the authors of a recent study in Chem Circularity contend that space cannot repeat those mistakes.

Primary sources of space debris include fragmentation events (65%), such as collisions, explosions from residual propellant, and spontaneous disintegration; decommissioned spacecraft and rocket bodies (30%); and mission-related objects (5%) unintentionally or deliberately released during operations. The rise in fragmentation has triggered a self-reinforcing cycle of collisions, posing escalating risks to orbital sustainability. Credit: Yang et al., iScience

Applying reduce, reuse, recycle to spacecraft design

The core idea is deceptively simple: apply the 3 Rs familiar from consumer electronics and automotive industries to spacecraft. That means designing satellites and launch systems to use fewer virgin materials, to be modular and repairable, and to allow for recovery and recycling at end of life. Practically, this could include:

- Modular architectures that let operators swap or upgrade payloads and avionics instead of replacing the whole satellite;

- Structural materials and fasteners chosen for durability under thermal cycling, radiation and micrometeoroid impacts, and for recyclability if recovered;

- Standardized interfaces for refueling, data, power and mechanical attachment so visiting servicing vehicles can maintain or repurpose older craft;

- On-orbit manufacturing or additive manufacturing hubs that produce replacement parts in space, reducing the need for fresh launches.

Designing with reuse in mind also reduces launch mass and cost across a satellite lifecycle. The paper's lead author, chemical engineer Jin Xuan of the University of Surrey, argues that 'a truly sustainable space future starts with technologies, materials and systems working together.' In other words, materials science, mechanical design and operations planning must be integrated from the outset.

Technologies that make reuse and recovery possible

Bringing hardware safely back to Earth, or to a processing platform in orbit, is a necessary capability for recycling. Soft-landing technologies — parachutes, airbags and controlled reentry capsules — can enable recovery of high-value components. Active debris removal methods, such as robotic arms, nets or harpoons deployed from servicing spacecraft, are being tested and could capture defunct objects for retrieval or in-orbit processing.

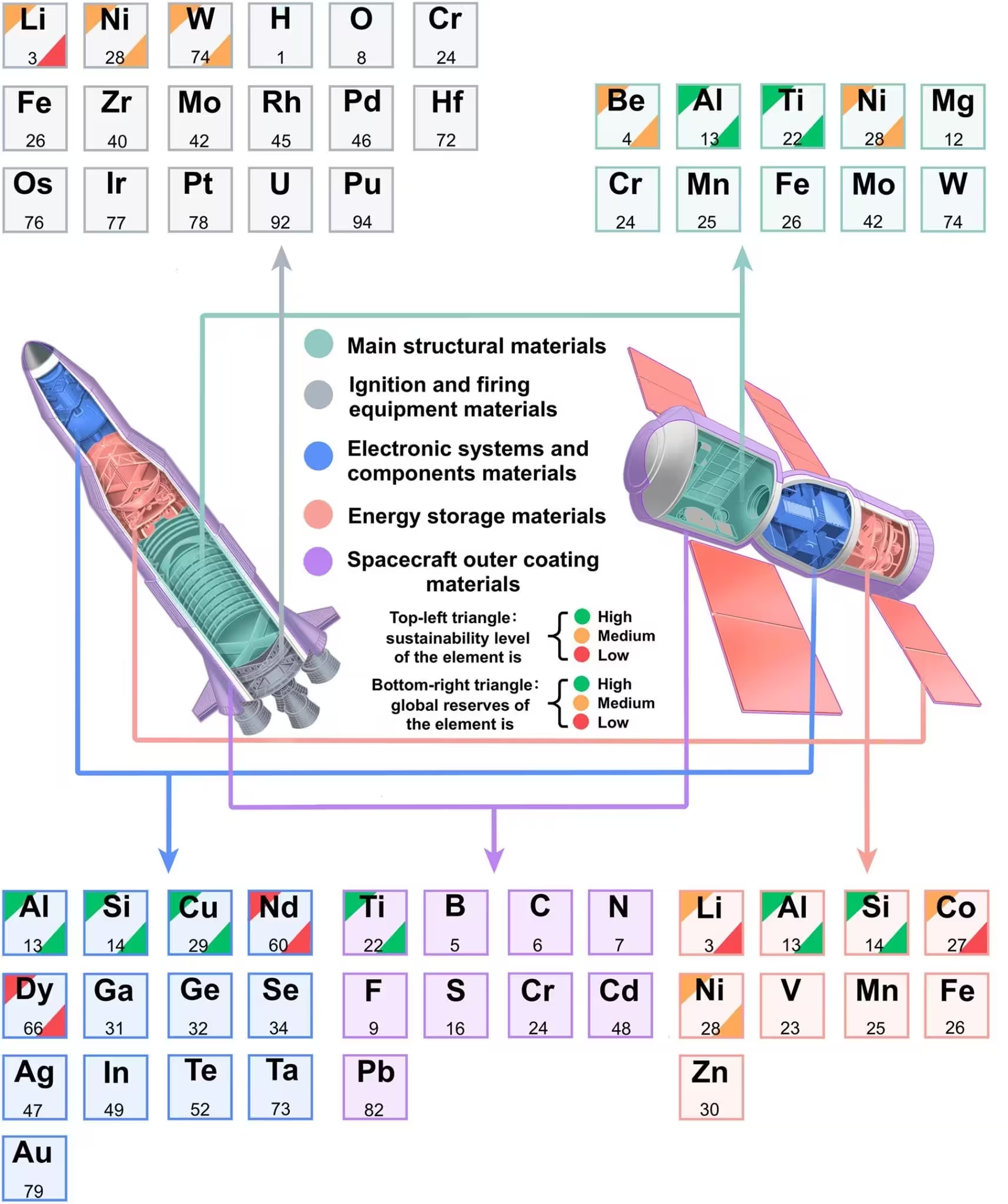

This schematic categorizes the principal chemical elements used across the major functional components of spacecrafts into five material domains: main structural materials, ignition and firing equipment, electronic systems and components, energy storage systems, and outer protective coatings. Each domain is color coded and spatially mapped onto simplified rocket and satellite models to reflect functional segmentation. Elements that are critically important, for either their high usage or unique functional roles, are annotated with corner triangles indicating their sustainability level (top left) and global reserves (bottom right); red, orange, and green denote high, medium, and low, respectively. Credit: Yang et al., iScience

Reused parts must pass strict qualification tests because the space environment imposes severe wear — thermal cycling, radiation damage and micrometeoroid erosion. Still, if validated, refurbished components could offset the need to manufacture and launch replacements, cutting greenhouse gas emissions and demand on critical mineral reserves.

Cleaning up orbit with robots and algorithms

Hardware recovery will be aided by data and digital tools. AI and advanced analytics can predict component aging, model fragmentation risk, and optimize rendezvous and capture maneuvers. Machine learning applied to satellite telemetry and ground-based observations can improve collision-avoidance and guide the prioritization of targets for removal or servicing.

For many tasks, simulations and digital twins reduce the number of costly physical tests, accelerating design cycles while saving material and energy. Autonomous servicing vehicles, guided by onboard AI, can perform inspection, docking, refueling and repair tasks with minimal ground intervention. Taken together, robotics and software provide the operational backbone for a circular approach in orbit.

Why policy and global cooperation matter

Moving to a circular space economy is not just a technological challenge — it is also an institutional one. International standards for modular interfaces, end-of-life procedures and material labeling would make it feasible for one nation’s servicer to work on another’s satellite. Export controls, liability rules and procurement policies need updating so that reuse, recovery and recycling are incentivized rather than punished.

As the paper points out, piecemeal solutions will not be enough. Systems thinking is required: the choice of alloys and coatings must be coordinated with manufacturing methods, mission planning and legal frameworks. Only then will sustainability become the default model rather than an afterthought.

Expert Insight

Dr. Maya R. Ortiz, a hypothetical senior systems engineer with two decades of satellite operations experience, comments: 'We can no longer view satellites as disposable. The economic case for servicing and recycling is getting stronger every year as launch costs fall and material shortages tighten. Startups and agencies are already proving that in-orbit refueling and robot-assisted repairs are technically viable. What we need next is common standards and shared commercial incentives to scale these capabilities.'

Whether through international policy, commercial innovation or materials breakthroughs, transforming spaceflight into a circular economy will require coordination across chemistry, engineering and governance. The prize is large: safer orbits, lower environmental costs, and a sustainable space industry that can support decades of exploration and services without creating an ever-growing cloud of junk around our planet.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

KaelX

Is this even realistic? Who pays to retrieve old sats, and won't geopolitics block common standards? if so, tough sell

coreflux

wow this is wild, didn't expect junk clouds like this... modular sats, on-orbit repair, yes pls! but hope policy catches up, fast

Leave a Comment