6 Minutes

A new study reveals that Earth’s deep interior remains far more dynamic than once believed, continents can slowly shed their lower layers, sending ancient material drifting beneath the oceans where it stirs new volcanic life.

Deep beneath Earth’s surface, a slow and surprising process appears to be reshaping the chemical fabric of the oceanic mantle. Researchers led by the University of Southampton report that fragments of continental roots — the dense, crystalline material that underpins continents — can be stripped away from beneath continental plates and swept laterally into the oceanic mantle. There, these relics of continental crust help fuel volcanic eruptions and leave a long-lived geochemical fingerprint hundreds or thousands of kilometres from their origin.

Peeling continents: a new way to move continental material

The idea is elegantly simple but geologically radical: continents are not just passive shells that break apart at the surface. Their deep roots can be destabilized and gradually removed, a process the team describes as a slow “peeling” from below. Using numerical simulations that model lithosphere–mantle interactions, the researchers show how tectonic stretching at continental margins can trigger a propagating instability — a mantle wave — that travels along the base of the continent at extremely slow rates. Over millions of years this wave can pluck fragments from depths of 150–200 km and carry them sideways into the adjacent oceanic mantle.

Once within the oceanic mantle, these continental fragments act as enriched chemical reservoirs. When melted or partially re-melted, they produce magmas with elevated concentrations of elements and isotopic ratios typical of continental crust. That helps explain a persistent mystery: volcanic islands far from plate boundaries, such as some seamounts in the Indian Ocean, often erupt rocks with chemical traits that seem ‘continental’ even though they sit in the middle of oceanic plates.

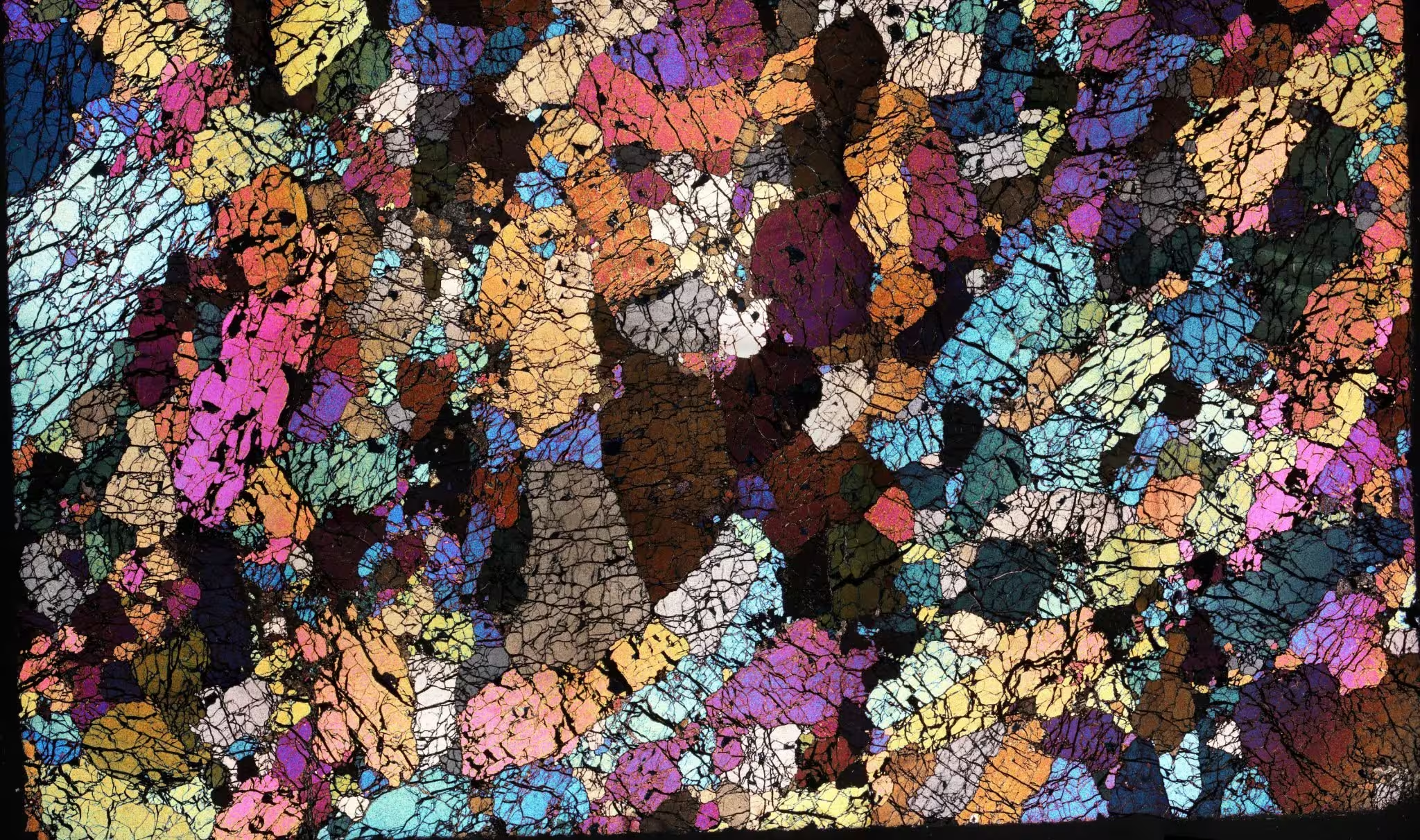

A piece of the lowermost continental mantle (the crystalline roots of the continents). This represents the material that the research proposes is removed and swept sideways into the oceanic mantle.

Geochemical clues from the Indian Ocean

The team combined geochemical analyses with their geodynamic models and applied the hypothesis to the Indian Ocean Seamount Province, a volcanic chain formed in the aftermath of the supercontinent Gondwana’s breakup more than 100 million years ago. Geochemical signatures in some of these seamounts record a burst of enriched magma soon after breakup, followed by a gradual fading of that signal over tens of millions of years. The timing and spatial distribution match the mantle-wave transport mechanism rather than classic explanations such as sediment recycling at subduction zones or deep mantle plumes.

“We’ve known for decades that parts of the mantle beneath the oceans look strangely contaminated, as if pieces of ancient continents somehow ended up in there,” said Professor Thomas Gernon of the University of Southampton, lead author of the study. “But we haven’t been able to adequately explain how all that continental material got there.”

How mantle waves work and why they matter

In the models, continental breakup induces a dynamic response in the mantle: a slow, rolling instability that propagates along the base of the lithosphere. This mantle wave perturbs the deep continental roots, causing fragmentation and lateral transport of dense continental material. Movement is glacially slow — roughly a millionth the speed of a snail — but over geological time this is enough to move blobs of material more than 1,000 km from their source.

Once deposited into the hotter, chemically distinct oceanic mantle, the continental fragments modify melting regimes. They generate enriched melts that can sustain volcanic activity long after the surface expression of rifting has moved on. Crucially, these enriched signatures persist without requiring a classical deep mantle plume rising from the core–mantle boundary.

“We found that the mantle is still feeling the effects of continental breakup long after the continents themselves have separated,” said Professor Sascha Brune of GFZ Helmholtz Centre in Potsdam, co-author of the paper. “The system doesn’t switch off when a new ocean basin forms — the mantle keeps moving, reorganizing, and transporting enriched material far from where it originated.”

Scientific background and broader implications

For decades, geoscientists have debated how oceanic volcanism acquires a continental chemical signal. Traditional hypotheses emphasized recycled sediments carried into the mantle at subduction zones or isolated deep upwellings called mantle plumes. Both remain important, but the mantle-wave mechanism explains anomalous cases where neither sediment recycling nor clear plume activity can account for the enriched chemistry.

Beyond explaining odd geochemical patterns, this mechanism reframes our view of mantle convection and lithosphere–mantle coupling. It implies continental break-up leaves a long-lived mark on mantle structure and composition, influencing volcanic activity and geochemical heterogeneity for tens of millions of years. That has implications for reconstructing plate tectonic histories, interpreting volcanic provinces, and understanding the deep carbon and volatile cycles tied to continental material.

Methods and collaboration

The study, published in Nature Geoscience, united geodynamic simulations with geochemical datasets. The international team included researchers from the University of Southampton, GFZ Helmholtz Centre Potsdam, University of Potsdam, Queen’s University (Canada), and Swansea University. Their simulations tested a range of rheologies, thermal profiles, and stretching regimes to show how mantle waves can form and transport continental material under realistic tectonic settings.

Expert Insight

“This work highlights how slow, subtle processes deep inside Earth can have outsized effects at the surface and in near-surface geology,” says Dr. Elena Márquez, a mantle dynamics specialist at a major research university (not involved in the study). “It’s a reminder that the mantle is not a uniform soup — it preserves pockets of history. Revealing how those pockets move and interact helps us link surface geology to deep Earth processes and refine models of volcanic hazard, mantle chemical evolution, and plate reconstruction.”

By showing that continental roots can be unmoored and relocated into oceanic domains, the study opens new directions for research into mantle heterogeneity, volcanic genesis, and the long-term chemical evolution of Earth’s interior.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

DaNix

is this even true? cool models, but are the geochem signals definitive or could plumes/sediment recycling still explain it. if that's real then big implications, hmm

labcore

wow, Earth keeps surprising me... continents peeling from below? mind blown. Ancient roots drifting under oceans and kicking off volcanos far away, wild stuff lol

Leave a Comment