6 Minutes

Deep beneath our feet, enormous and oddly behaving structures at the core–mantle boundary are rewriting parts of Earth’s origin story. New geodynamic research suggests these features may be relics of a molten early Earth that mixed with material leaking from the core — a process that could have helped shape our planet's cooling, volcanism, and ultimately its ability to support life.

Strange structures at Earth’s core–mantle boundary may be relics of early core–mantle mixing, revealing new clues about how our planet formed, cooled, and ultimately became uniquely habitable.

Unraveling the deep anomalies: What scientists actually see

Seismologists have long detected two puzzling features sitting roughly 1,800 miles (≈2,900 km) beneath Earth’s surface: large low-shear-velocity provinces (LLSVPs) and ultra-low-velocity zones (ULVZs). LLSVPs are colossal regions beneath Africa and the Pacific where seismic shear waves slow unusually, signaling hot, dense, or chemically distinct rock. ULVZs are thinner, patch-like zones bordering the core where seismic waves slow even further — suggesting partially molten or compositionally altered material.

These anomalies are not merely curiosities. Their size, longevity and seismic signature imply a chemical recipe different from the surrounding mantle. For decades, models that start from a global magma ocean — a molten early Earth — failed to produce such uneven remnants. Geoscientists expected clear compositional layering as the planet cooled; instead, seismology shows irregular, clustered patches near the base of the mantle.

A missing ingredient: Could the core have leaked?

Rutgers geodynamicist Yoshinori Miyazaki and collaborators propose a bold fix: material from the core leaked into the basal magma ocean during the planet’s early cooling, mixing with mantle silicates and preventing neat layering. Over billions of years this mixed material would solidify into chemistry distinct enough to produce the LLSVP and ULVZ seismic signals we detect today.

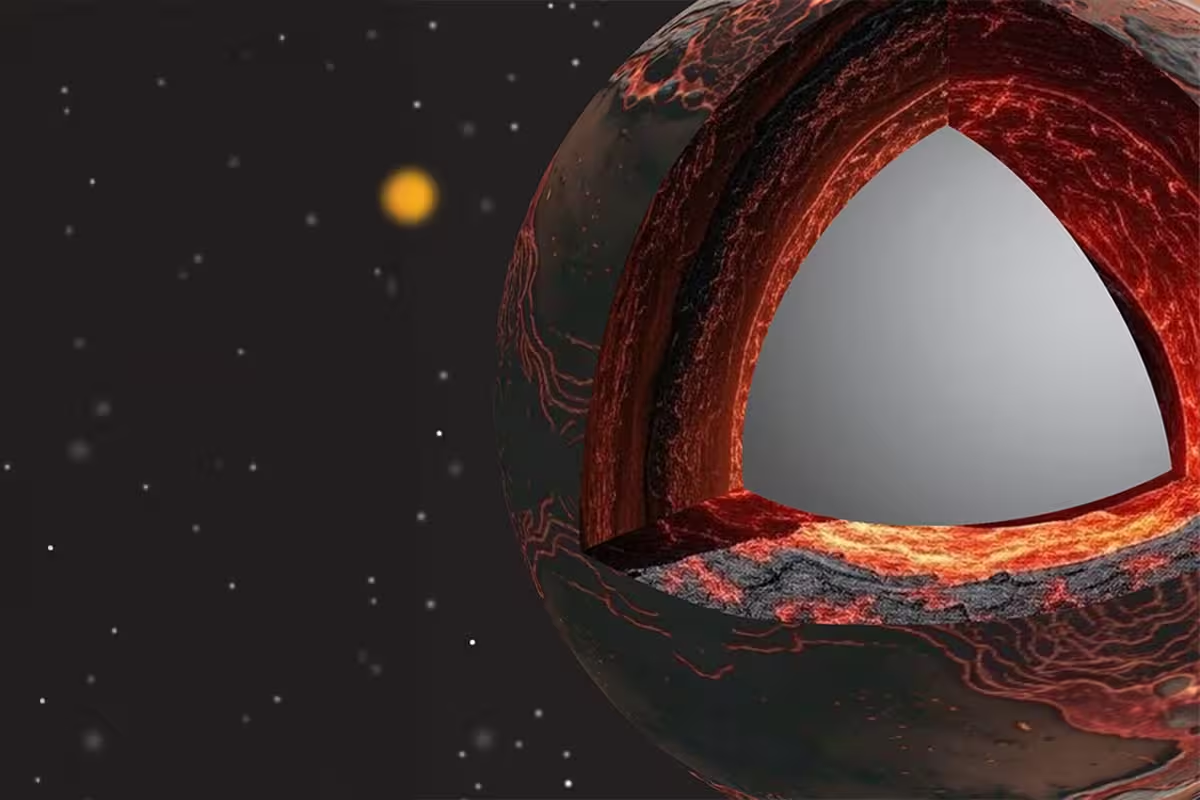

The illustration shows a cutaway revealing the interior of early Earth with a hot, melted layer above the boundary between the core and mantle. Scientists think some material from the core leaked into this molten layer and mixed in. Over time, that mixing helped create the uneven structure of Earth’s mantle that we see today.

In plain terms: imagine a global lava ocean where metal-rich droplets from the core bleed upward and mingle with silicate melt. As cooling proceeds, instead of forming neatly separated chemical layers, the system freezes into blobs and streaks — the deep heterogeneities now imaged by seismic waves.

Methods: How the team built the case

To test the hypothesis, the research team integrated three pillars of Earth science: seismic observations that map velocity anomalies, mineral physics that constrain how materials behave at extreme pressures and temperatures, and geodynamic modeling that simulates flows and mixing in the early mantle and basal magma ocean. The combination allowed them to show that adding a realistic core-derived component (for example, extra silicon and magnesium) into a basal magma ocean can reproduce the seismic signatures of both LLSVPs and ULVZs.

That multi-disciplinary approach is crucial. Seismology identifies the anomalies; mineral physics says which compositions and phases could cause the observed velocity reductions; and geodynamic models test whether such compositions could form and persist over geological time.

Why this matters for Earth's habitability

Linking deep mixing to surface habitability might seem indirect, but the stakes are high. Core-mantle exchange affects how heat leaves the planet, how mantle convection evolves, and where volcanism concentrates. All of these influence the generation of a magnetic field, volatile cycling (including water and gases), and long-term climate stability — factors that distinguish Earth from its neighbor planets.

“These are fingerprints of Earth’s earliest history,” Miyazaki says, explaining that understanding why these structures exist helps us understand how Earth formed and why it became habitable. Co-author Jie Deng of Princeton notes that the deep mantle may still carry chemical memories of ancient core–mantle interactions, opening new ways to interpret planetary evolution.

Surface connections: Hotspots, volcanism and atmosphere

Some researchers now propose that LLSVPs and ULVZs could feed mantle plumes that create volcanic hotspots like Hawaii and Iceland. If these deep regions are compositionally distinct and relatively hot, they can act as long-lived sources of plume generation — linking the deepest Earth to island chains, flood basalts, and surface degassing events that shape atmosphere and oceans.

Understanding whether and how the core contributed to these reservoirs helps explain differences among Earth, Venus and Mars: internal dynamics, heat loss, and volatile delivery all shape surface conditions. For example, factors that allowed sustained outgassing and plate tectonics on Earth may have been tied, in part, to how the deep interior mixed and released heat and material over time.

Expert Insight

Dr. Laura Chen, planetary geophysicist at the Institute for Planetary Physics, offers perspective: “The idea that core material could infiltrate a basal magma ocean and leave a chemical imprint we still see today is powerful. It connects initial conditions right after planet formation to processes that control volcanism, magnetic fields, and volatile cycles. This work helps close a loop between the deep interior and surface conditions that make Earth habitable.”

For the scientific community, the study highlights that even the deepest structures can carry a long memory of planetary formation. Each new constraint from seismic imaging, laboratory mineral physics, or improved geodynamic simulations refines that narrative and helps us compare Earth to other rocky planets.

Next steps and future prospects

Future research will aim to quantify the exact composition and volume of core-derived material in the basal mantle, and to trace how these reservoirs influence mantle convection and plume formation through time. Improving seismic imaging, high-pressure experiments, and three-dimensional models of early Earth will be critical.

As models converge with observations, we may soon read the deep interior like a fossil record — not of life, but of the hidden processes that made life possible on our planet.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

DaNix

Is this even true? If metal droplets bled up, why didn't everything homogenize over billions yrs... Seismic hints ok, but sounds speculative to me, needs more tests

labcore

Totally blew my mind, earth's deep memory? Wow. If core leaked into a magma ocean, that’s wild, kinda poetic and scary. Makes hotspots feel ancient…

Leave a Comment