6 Minutes

A single-celled organism discovered in the steaming pools of Lassen Volcanic National Park has rewritten what scientists thought possible for complex life. The newly described Incendiamoeba cascadensis thrives and divides at temperatures up to 63 degrees Celsius (145°F), a record for eukaryotic organisms and a dramatic expansion of the thermal limits for life with nuclei and organelles.

A record-breaker: a eukaryote that prefers the heat

Most eukaryotes — the domain of life that includes amoebae, plants, animals, and fungi — favor relatively mild temperatures. Humans and many animals function best near 20–37°C, and for decades researchers assumed eukaryotic cells would fail above roughly 60°C because their complex internal membranes and organelles are fragile under heat stress.

Incendiamoeba cascadensis overturns that assumption. Isolated by a team led by H. Beryl Rappaport and Angela Oliverio at Syracuse University and reported in a bioRxiv preprint, this 'fire amoeba' only begins to grow above 42°C — making it an obligate thermophile — and shows optimal growth around 55–57°C. The researchers directly observed cell division (mitosis) at 58°C and at the milestone temperature of 63°C, surpassing the previous amoeba record of 57°C set by Echinamoeba thermarum.

Field to flask: how researchers tested extreme limits

Rappaport, Oliverio, and colleagues collected hot-water samples across Lassen between 2023 and 2025, recovering the amoeba from 14 of 20 sampled sites. In the lab they cultured separated samples in multiple flasks, adding wheatberry to stimulate bacterial growth for the bacterivorous amoeba to feed on. Temperature became the key experimental variable: 17 temperature conditions from 30 to 64°C were tested, four replicate flasks per temperature.

I. cascadensis remained inactive below 42°C, flourished between about 55 and 57°C, and continued moving at 64°C. At 66°C it began forming protective cysts — a dormancy strategy — and cyst formation was also observed at 25°C, an unusually high lower limit for encystment. Movement ceased at 70°C, but samples could revive after cooling, with irreversible death only observed near 80°C.

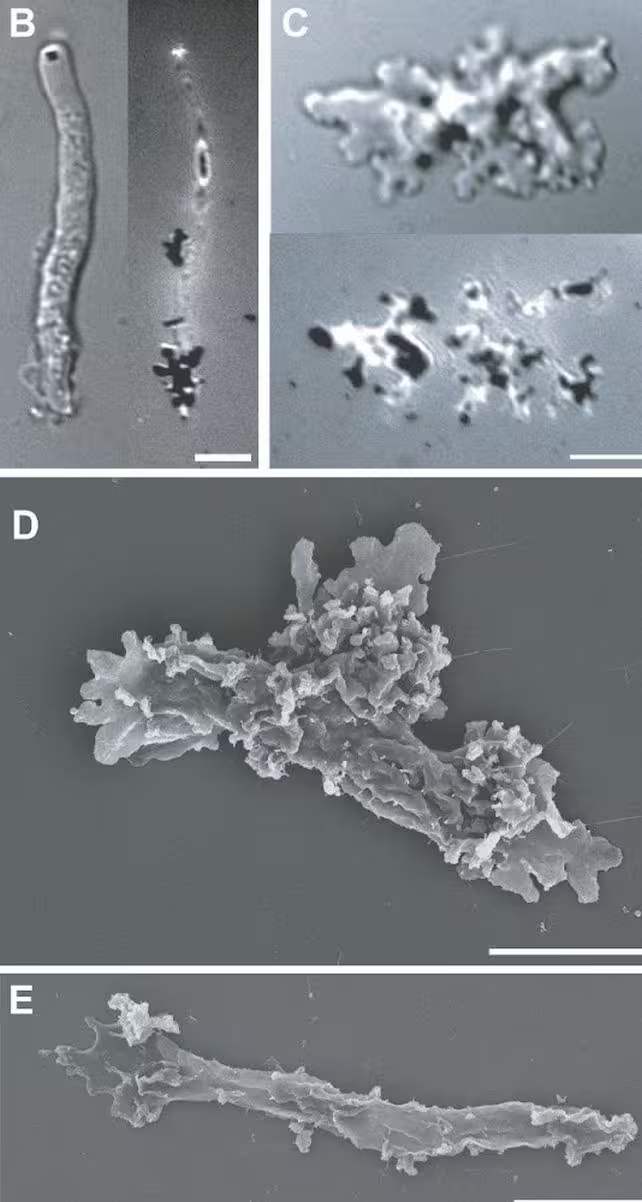

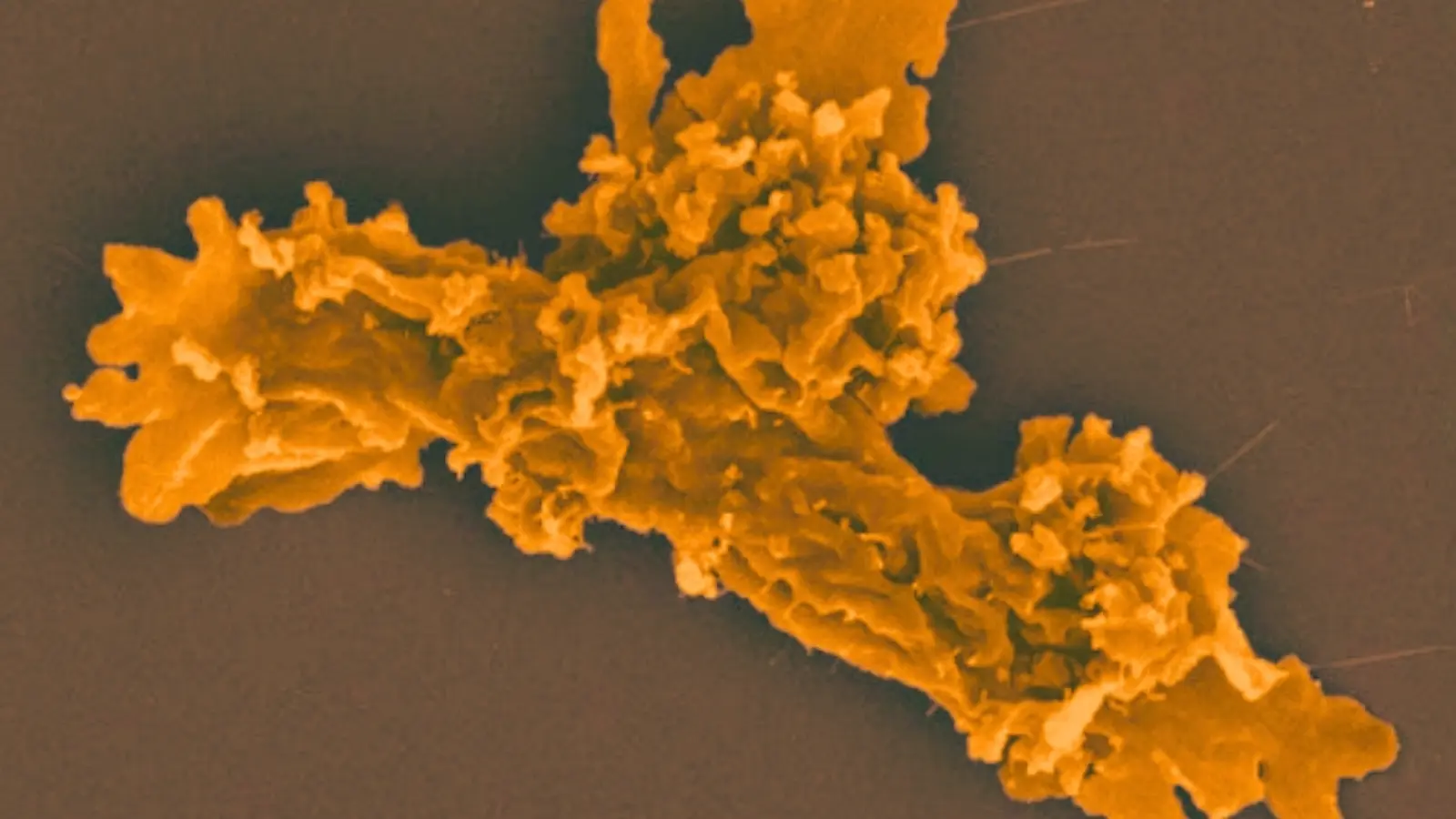

I. cascadensis in its elongated vermiform state for faster motion (B, E) and amoeboid state for feeding and exploring (C, D). (Rappaport et al., bioRxiv, 2025)

Genomics and survival strategies: what makes this amoeba heat-proof?

Genome analysis provided clues. The amoeba's DNA encodes expanded sets of heat-shock proteins and chaperones — molecular helpers that stabilize other proteins under stress — plus adaptations for rapid cellular signaling and heat-response pathways. These molecular features likely protect membranes and essential protein complexes from denaturation at temperatures that would cripple most eukaryotes.

Unlike the hardiest prokaryotes — for example the archaeon Methanopyrus kandleri that survives at more than 100°C on deep-sea vents — eukaryotes carry delicate internal membranes and organelles such as mitochondria and nuclei. The discovery of a eukaryote that not only tolerates but requires such high temperatures forces a re-evaluation of evolutionary constraints on cellular complexity.

Where else might the fire amoeba live?

Environmental DNA sequences nearly identical to I. cascadensis appeared in samples from Yellowstone National Park and New Zealand’s Taupō Volcanic Zone. Environmental DNA isn’t a whole organism, but these fragments indicate the amoeba — or close relatives — may be more widespread in geothermal systems than the initial Lassen samples suggest.

That geographic distribution is important: if heat-adapted eukaryotes exist across hydrothermal locales on Earth, it expands the kinds of environments considered potentially habitable for complex cells elsewhere in the Solar System or beyond.

Why this matters for ecology and astrobiology

The implications are broad. Practically, heat-tolerant eukaryotic proteins and chaperones could inspire industrial enzymes that function at high temperatures, improving processes in biotechnology or materials science. Ecologically, obligate thermophiles like I. cascadensis help shape microbial food webs in geothermal ecosystems, where they graze on bacteria and interact with other extremophiles.

For astrobiology, the discovery challenges conservative assumptions about where life can exist. Many models for extraterrestrial habitability exclude high temperatures for complex life. If eukaryotic cells can operate and divide at temperatures above 60°C, the range of candidate environments on worlds such as ancient Mars, icy moons with subsurface hydrothermal activity, or exoplanets with geothermal hotspots may need to be reconsidered.

Expert Insight

'This finding widens the envelope for eukaryotic life,' says Dr. Lina Ortega, a microbial ecologist not involved in the study. 'We tend to assume complexity equals fragility, but Incendiamoeba cascadensis shows that cellular complexity can be compatible with extreme heat when evolution selects for supporting molecular systems. From an astrobiology standpoint, that means we should broaden the kinds of planetary niches we model and seek.'

Next steps and open questions

Important questions remain. How did I. cascadensis evolve its heat-stable machinery — by vertical inheritance, horizontal gene transfer, or a mix? What are the limits of its metabolic flexibility, and can it tolerate other extremes such as high acidity or pressure? Long-term ecological surveys, comparative genomics, and laboratory experiments probing protein stability will help answer these questions.

Rappaport and Oliverio's team has posted their work as a preprint on bioRxiv, inviting peer review and follow-up studies. Whether this discovery marks an isolated evolutionary curiosity or the first of many known 'hot' eukaryotes, it already forces a scientific rethink: complex life can persist in far hotter places than we once believed, and those places deserve a second look in terrestrial and extraterrestrial habitability studies.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

atomwave

Is this even true? samples from Yellowstone and NZ sound promising, but preprint only, peer review matters... also, any pics of mitosis at 63°C??

bioNix

wow wow, this is wild. single-celled rewriting rules? if true, mind blown. curious how mitochondria cope, proteins must be crazy stable. gotta read more

Leave a Comment