5 Minutes

New research suggests a subset of brain immune cells can switch into a protective state that slows hallmark Alzheimer’s pathology in mice. Understanding this switch could point to immunotherapy approaches that coax the brain’s own defenders to fight the disease.

When defenders turn into protectors: microglia's surprising role

Microglia are the brain’s resident immune cells: they clear debris, prune synapses and respond to injury. In Alzheimer’s disease, their activity has appeared conflicted — sometimes clearing toxic proteins, other times amplifying damaging inflammation. A multinational team led by neuroscientist Pinar Ayata at the Icahn School of Medicine mapped how microglia shift between these opposing modes in mouse models of Alzheimer’s.

Using detailed molecular profiling and imaging, the researchers found that microglia that migrate toward amyloid-beta protein clumps — a defining feature of Alzheimer's — can enter a distinct neuroprotective state. In that configuration the cells both slow amyloid accumulation and limit tau aggregation, the two toxic protein processes most associated with cognitive decline.

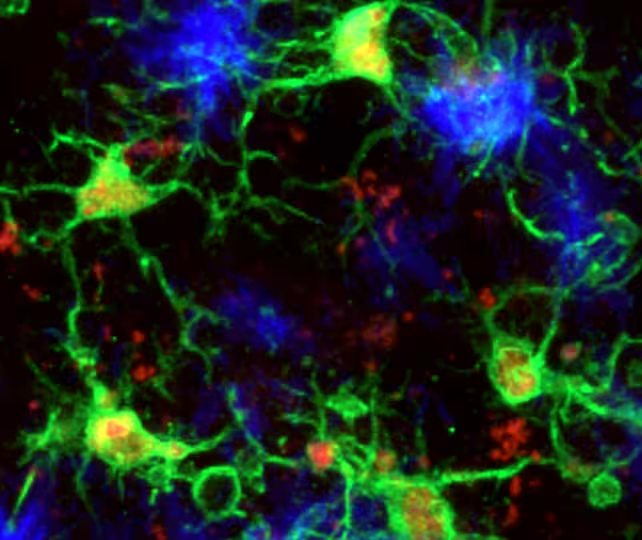

Microglia (green) responding to amyloid-beta plaques (blue) in the mouse brain.

PU.1 and CD28: a molecular signature of protection

The protective microglia share two key molecular features: reduced levels of the transcription factor PU.1 and higher expression of CD28, a receptor usually linked to peripheral immune T cells. When microglia express this combination, they appear better equipped to limit the growth of amyloid-beta plaques and to suppress tau aggregation in these mouse experiments.

To test cause and effect, the team genetically blocked CD28 production in mice. The result was a shift back toward inflammation-prone microglia, more amyloid plaques, and a clear loss of the protective phenotype. Those manipulations strengthen the argument that CD28 and PU.1 levels help determine whether microglia act as guardians or aggressors.

Genetic data from humans also support the biology: people with natural variations that reduce PU.1 expression in specific brain cell types tend to develop Alzheimer’s later than average. That correlation offers a plausible mechanistic link between genes and disease timing.

What this means for therapies and future research

Turning microglia into long-lived protectors is a tantalizing idea for new Alzheimer's treatments, but it comes with caveats. Alzheimer’s is a multifactorial disease — genetics, environment, vascular health and aging all contribute. Any successful therapy will likely need to address several targets at once.

- Immunomodulation: Designing drugs or biologics that raise CD28 signalling in microglia or modulate PU.1 could nudge cells into the protective state.

- Safety and specificity: Therapies must avoid broadly boosting immune activation, which can worsen neuroinflammation.

- Translation: Mouse microglia and human microglia are similar but not identical — confirming the same protective program exists in people is a critical next step.

Experts quoted in the study underline both the promise and the caution. Anne Schaefer of the Icahn School of Medicine notes that microglia "are not simply destructive responders in Alzheimer's disease—they can become the brain's protectors," while geneticist Alison Goate says the work helps explain why lower PU.1 levels are associated with reduced Alzheimer's risk. Rockefeller University epigeneticist Alexander Tarakhovsky links the finding to broader immune regulation, suggesting the brain's protective microglia echo regulatory T cells found elsewhere in the body.

Expert Insight

"This study adds an important piece to the Alzheimer’s puzzle by showing how immune identity in the brain can be beneficial rather than purely detrimental," says Dr. Maya Elfenbein, a neuroimmunologist and science communicator. "The challenge now is twofold: prove the same mechanism operates in humans, and then develop precise ways to flip microglia into that protective state without triggering harmful inflammation."

Looking ahead, the research opens a path toward immunotherapeutic strategies that treat Alzheimer's not only by clearing proteins but by reprogramming the brain’s own immune cells. That route could complement approaches such as antibody therapies, small molecules that target tau, and lifestyle interventions that reduce risk.

While this microglial defense is a promising natural barrier, the authors emphasize it is not sufficient to halt disease progression on its own. Still, converting microglia into protectors — if achievable in humans — would add a powerful new tool to the Alzheimer's research and treatment toolkit.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

Tomas

Sounds promising but is mouse microglia = human tho? Tons of translation gaps, and boosting CD28 sounds risky, could trigger inflammation??

neuroLab

Whoa microglia turning into protectors? That's wild, kinda gives hope but also freaks me out... if we can nudge cells safely this could be huge

Leave a Comment